This book made available by the Internet Archive.

Our efforts arc

dedicated

to

Monsignor Florence D. Cohalan,

Historian, Archdiocese of New York

and to

Joseph A. Bierbauer

1929-1989

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION

What I have written does not belong to me. If I have written the truth, then it is "God's truth"; it would be true if every human mind denied it, or if there were no human minds in existence to recognize it. It is the obverse of that reality, that factualness, which belongs to some of our ideas and not to others; belongs to them, not in their own righthow could it?but as lent to them by you, who are the focus and the background of all existence. If I have written well, that is not because Hobbs, Nobbs, Noakes and Stokes unite in praising it, but because it contains that interior excellence which is some strange refraction of your own perfect beauty; and of that excellence you alone are the judge. If it proves useful to others, that is because you have seen fit to make use of it as a weak tool, to achieve something in them of that supernatural end which is their destiny, and your secret.

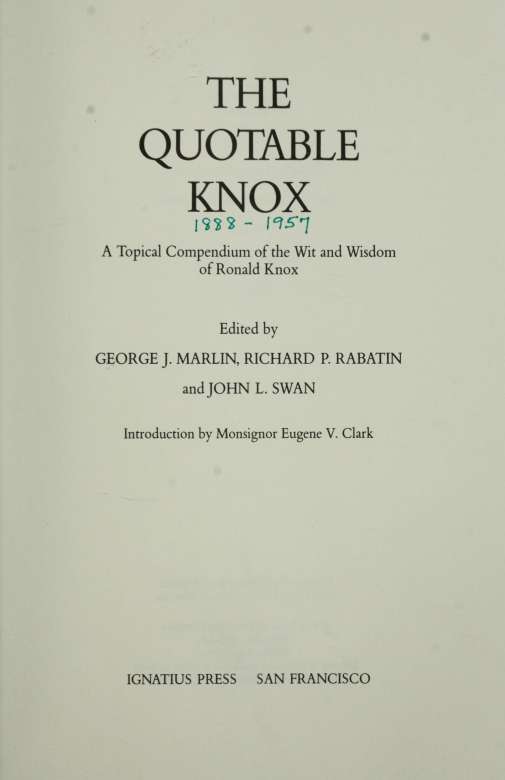

These words of Ronald Knox, discovered after his death, were to be part of a preface to an unfinished work of apologetics. Evelyn Waugh rightfully declared that they "may stand as the epitaph of his life's work".

Like G. K. Chesterton and Fulton Sheen, Knox was a champion of what T. S. Eliot called the "Permanent Things". Throughout his long career, this scholar, preacher, essayist, poet, and mystery writer always defended the common man against the elite's latest fads and vices.

This man, who brought the Vulgate to life for twentieth-century man, believed that effectively to combat the modernists one must merely "trust orthodox tradition to determine what he is to believe, and common sense to determine what is orthodox tradition". It is the hope of the editors that the quotations excerpted from Ronald Knox's works give the reader a sense of that orthodox Tradition.

We are grateful to the following for their support: Larry and Pat Azar, Monsignor Eugene V. Clark, Monsignor Florence Cohalan, Michael G. Crof-ton, Mike Long, Patrick Foye, Joe Mysak, Rev. George William Rutler, Thomas Walsh, and Msgr. John Woolsey. At The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, particular thanks to John Haley, Paul Blanco, Frank Bruno, Lysa Meduri, Sheree Van Duyne and Jean Ruane for putting up with one of the editors.

George J. Marlin Richard P. Rabatin John L. Swan

The City of New York May 24, 1996

INTRODUCTION

I am delighted to introduce Ronald Knox to those who do not know him. All my adult life he has been a private pleasure, a delight expected and delivered, a literary and higher satisfaction on which to reflect and be pleased.

He is a happy part of the intellectual and esthetic life of so many who love fine English prose; who rejoice in the joie de vivre that bursts suddenly from this hooded, diffident person; who discern the apostolic roots of a devotional life that steadied his easily injured person. His uncommon literary gifts, restricted social instincts, and unlimited imagination, his bouts with self-doubt and dejection were all carried nicely by his deep trust in Christ and the dignity of an honorable priest.

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (1888-1957), son and grandson of evangelical Anglican bishopstrue believers was born into a family of uncommon brightness and scholarly gifts. His childhood was filled with profound goodness and enlivening opportunities to learn and imagine, memorize the best, and wrestle with intellectual puzzles. His niece wrote, "As for Ronnie, the little boy who had been asked at four years old what he liked doing and had replied, 'I think all day, and at night I think about the past,' was already a natural philosopher". 1 At six he wrote letters salted with Greek and Latin words. He attended Eton and Balliol College, by contemporary estimate the fmest schools in England in the attention they gave to students.

These were his advantages, and not much was lost. But he did not live in secure circumstances. As a small boy he lost his mother; he lived in no great homes. His family had not enough money for his schools; he had to win scholarships to each. All his life he had to be careful of money, and he worked hard, young and old, not to burden anyone.

From childhood he loved Church life and normal religious practice, and long before he ever saw a ritual service, he came to love ritual because he felt every object associated with worship was sacred. As two brothers slipped into agnosticism, Ronald taught himself sharp distinctions that served him well. Early he distinguished ritual, theology, and faith as exercises of very different value. An irredeemable romantic in religious matters (he loved Bruges as Catholic and Robert Hugh Benson's novels), he rejoiced in a sceptical mind ever demanding clear, supported truth. He was wary of theo

1 Penelope Fitzgerald, The Knox Brothers (London: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, 1977), p. 46.

logical vagueness and intellectual shortcuts. His biographer, Evelyn Waugh, wrote:

Such temptations against the Faith as he sufferedand he was near despair in the year before his reception into the Catholic Churchwere total. Either the whole deposit of Faith was divinely inspired and protected and developed under divine guidance, or it was false. He never saw it, as did many of the contemporaries with whom he now took issue, as the agglomeration of history and fable, of hints and shadows of Truth, of vestigial philosophic notions and dark superstitions from which anyone could pick at will whatever he found agreeable, and discard the rest. He was for some years uncertain where he could find the authority which guarded and administered the Faith, but he always recognized it as a single, indivisible world. 2

Nor did relaxing intellectually into the Faith diminish his sceptical approach to invention in Catholic doctrine and emotion-tinged theological conclusions. This was, of course, not the scepticism unbelievers proclaim but the mind of a clear-headed believer wanting to trust only purest apostolic teaching, and the longing of a scholar for clear, sure conclusions as a base for further reflection. Many other "truths" of religion he thought dangerous mush. One of his earliest pieces as an Anglo-Catholic was the often reprinted Absolute and Abitofhell (in the style of Dryden), in which he lampooned the waffling Anglican hierarchy. As an Anglican, early on, he saw that the first danger to the Church was not Protestantism, as most Anglo-Catholics thought, but modernism. Oddly, too, for an early ritualist, he considered the externals and consolations of religion very minor factors in spirituality. His sound thinking in this kept his sharp esthetic sense well grounded and also nicely liberated. He groaned inwardly at the wording of Catholic hymns and official prayers. But he never injured the feelings of those who profitted from those prayers.

Was it perhaps his demanding mind in limning the final verities that allowed him to abandon himself to comic devices in lectures and wild charades? He was so entertaining and delightful to high school girls that they were known to race home so as not to miss his talks. At Oxford he completed a lecture, offering his conclusions muffled in a gas mask.

Next page