Preface

Professors Paul Kurtz and William Lane Craig came to Franklin and Marshall College in October of 2001 to debate the question that serves as this books title: Is goodness without God good enough? Kurtz argued for the affirmative position and Craig the negative. After opening statements, they engaged in two rounds of rebuttal, followed by closing statements.

Months later, Kurtz and Craig agreed to publish the debate alongside a collection of new essays on the topic. The editors were fortunate to secure contributions from prominent scholars who represent a wide range of views about the relationship (if any) between God and ethics. These resulting essays both comment on the Kurtz/Craig debate and advance the discussion of the many important issues that arise therein. The volume closes with a pair of essays containing final reflections from Craig and Kurtz.

Some of our authors argue for a tight connection between God (or belief in God) and ethics. William Lane Craig argues that theism, and only theism, can serve as a metaphysical foundation for objective moral values, duty, and accountability. John Hare argues that the rational status of morality is undermined, absent belief in God. C. Stephen Layman argues that certain plausible and traditional claims about morality support the claim that God exists. Other authors (Paul Kurtz, Louise Antony, Donald Hubin, and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong) argue that a wide range of traditional ethical beliefs fit comfortably within a secular worldview. Moreover, they add, such beliefs cannot gain support from theism. Still other authors (Mark Murphy and Richard Swinburne) argue for positions that in important respects lie between the views mentioned above. The overall result is a multifaceted discussion among first-rate scholars, all of whom take morality seriously. We the editors hope that the discussions in this book will benefit students, scholars, and laypersons who wish to think more carefully about religion and morality.

We have a long list of people to thank for helping us bring this project to completion. We would first like to thank Franklin and Marshall College for sponsoring the debate that was the genesis of this volume. Thanks to Michael Murray, who organized the debate on behalf of the Bonchek Institute for Rational Thought and Inquiry at Franklin and Marshall (now known as Bonchek Institute for Reason and Science in a Liberal Democracy). We are especially grateful to Mike for encouraging us to take on this project and for providing invaluable advice throughout the editorial process. Mikes wisdom and encouragement were simply essential to this books success. Thanks also to Suzanne Campbell (Suzanne Farmer at the time) for her tireless efforts on behalf of the Institute and the event. Our teachers David Solomon and Jim Sterba provided generous and helpful advice at crucial points in the development of this project, including our preparation of the introduction. Likewise, William Lane Craig, Paul Kurtz, and Mark Murphy read various drafts of the introduction and provided many helpful suggestions. Others to whom appreciation is owed include Louise Antony, Robert Audi, Terrence Cuneo, C. Stephen Evans, Doug Geivett, John Hare, Donald Hubin, Steve Layman, Michael Loux, Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, and Fritz Warfield. We also thank Ross Miller, Ruth Gilbert, and Janice Braunstein of Rowman & Littlefield Publishers for their abundant good advice and considerable patience in working with a pair of rookie editors.

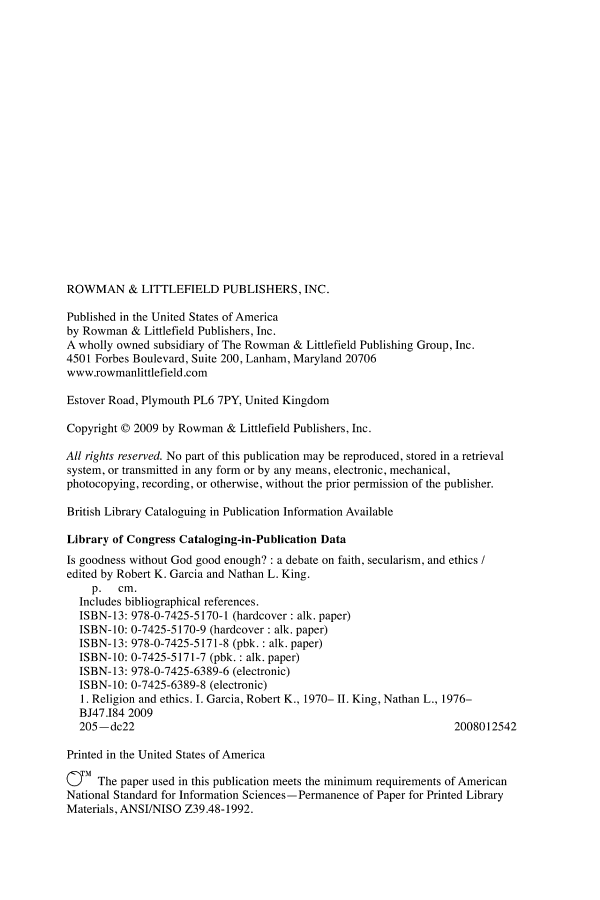

We are grateful to C. Malcolm Powers for generously allowing us to use a photo of his bronze sculpture, Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law, as our cover image, and to Kurt Hillig for the photo itself. Thanks also to Marion Powers for arranging the photo shoot of Malcolms work. More of Malcolms work can be viewed at http://www.cmalcolmpowers.com.

We are grateful to our parents, Joe and Evelyn Garcia and Jim and Dede King, for many more acts of kindness and support than we could possibly recount. Thanks to (one-year-old) Joel Garcia, for reminding us that lifes most important lessons arent always learned from books. Finally, we thank our wives, Amy Garcia and Kristie King, who provided a great deal of encouragement and tolerated frequent absences while we carried out this project. We gratefully dedicate this volume to them, without pretending that we have thereby begun to repay their loving support.

Introduction

Robert K. Garcia and Nathan L. King

[T]he lesson of todays terrorism is that if God exists, then everything, including blowing up thousands of innocent bystanders, is permittedat least to those who claim to act directly on behalf of God, since, clearly, a direct link to God justifies the violation of any merely human constraints and considerations.

Slavoj iek, Defenders of the Faith, New York Times, March 12, 2006

[T]hose are not to be tolerated who deny the being of a God. Promises, covenants, and oaths, which are the bonds of human society, can have no hold upon an atheist. The taking away of God, though but even in thought, dissolves all.

John Locke, A Letter concerning Toleration

Dostoyevsky is reported to have written, If God does not exist, then everything is permitted. This claim expresses a belief that has been widely held throughout the history of Western culture. The belief is that unless God exists, ethics is in serious trouble. This idea has seemed so obvious to some that it has been deployed as a premise in so-called moral arguments for the existence of God. In general, moral arguments have the following form:

1. If God does not exist, then some apparent and important feature F of ethics or the ethical life is illusory.

2. The apparent feature F of ethics or the ethical life is not illusory.

3. Thus, God exists.

Arguments of this form can be grouped into families in terms of the different features of morality for which God is alleged to be necessary. Some moral arguments, for instance, aim to show that the apparent objectivity of ethical claims requires a theistic foundation. Other arguments focus on the apparent fact that moral reasons for action override all other kinds of reasons, and argue that there is no such fact if God does not exist. And, according to a third kind of moral argument, Gods existence is needed to ground the apparent fact that the moral life is not futile. Many other kinds of moral arguments can be found in the literature.1

Moral arguments have occupied a relatively prominent place in the history of Western philosophy. Such arguments are part of a larger projectoften called natural theologythat aims to support theistic belief by appeal to premises that are knowable by human reason or observation (and independent of special revelation from God). This project involves the articulation and defense of various arguments for the existence of God, such as design arguments, cosmological arguments, ontological arguments, and moral arguments. Natural theology was widely regarded as an intellectually viable project prior to the Enlightenment, and the arguments for Gods existence are currently a topic of much discussion.2

The popularity of moral arguments, in particular, has likely been due to a widespread assumption that morality depends upon God. In keeping with this assumption, some have thought that nonbelievers cannot be trusted to act morally. The following comment by John Locke (16321704) is typical: