Dedication

For Adrienne

Copyright page

First published in French as La nature est un champ de bataille. Essai dcologie politique, (c) ditions La Dcouverte, Paris, France, 2014

This English edition (c) Polity Press, 2016

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-0377-3 (hardback)

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-0378-0 (paperback)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 10.5 on 12 pt Sabon Roman by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives PLC

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Keucheyan, Razmig, author.

Title: Nature is a battlefield : towards a political ecology / Razmig Keucheyan.

Other titles: Nature est un champ de bataille. English

Description: Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA : Polity Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016006440 (print) | LCCN 2016018681 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509503773 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 1509503773 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781509503780 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 1509503781 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781509503803 (mobi) | ISBN 9781509503810 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Political ecology. | EcologyPolitical aspects. | Environmental disastersPolitical aspects. | Human ecologyEconomic aspects. | Environmental justice.

Classification: LCC JA75.8 .K4813 2016 (print) | LCC JA75.8 (ebook) | DDC 304.2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016006440

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:

politybooks.com

The experience of our generation: that capitalism will not die a natural death.

Walter Benjamin

Introduction

In Autumn 1982 the inhabitants of Warren County in northeast North Carolina mobilized for six weeks in opposition to a toxic waste landfill being situated in their area. Four years previously, in 1978, an industrial waste management company had illegally dumped large quantities of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) a substance used, among other things, in paint and in electrical transformers. Once these PCBs had been discovered, the state of North Carolina decided to acquire a site where it could bury them and, after looking into many possible locations, it finally opted for one close to the town of Warrenton. As is often the case in this type of situation, local residents opposed the plan, fearing for its impact on their health (as PCBs are carcinogenic substances). They launched a legal bid to stop the waste being dumped in their area but, two years later, the district tribunal rejected their complaint. It was then that the protest took on extra-judicial forms, with demonstrations, sit-ins, boycotts, civil disobedience, marches, meetings, road blockades These actions led to the arrests of over five hundred people, including various local and federal representatives. In the short term, the movement did not succeed in getting the project withdrawn and only in the 2000s would the site be decontaminated.

The arguments that the protestors initially raised in opposition to the landfill site related to the pollution of the environment (both the water and the soil) by PCBs and the health risks that this substance posed. Yet as the movement expanded and became more politicized, the nature of its arguments changed. The residents and their allies insisted that the state had chosen this site for burying the toxic waste because it was an area inhabited by Blacks, poor people and above all poor Blacks. To put it another way, there was a racist basis for the decision to locate the dump there. At the time, Warren County had a 64 per cent Black population, with the corresponding figure for the area immediately next to the dump rising to 75 per cent. In its environmental management and resources policy, the state systematically favours White populations and the middle and upper classes, which it protects from this type of harmful substances. Conversely, minorities including not only Blacks, but also Native Americans, Hispanics and Asians, as well as the poor bear the brunt of industry's negative consequences. We can see that, still today in the United States, the improper handling of waste in the vicinity of White neighbourhoods leads to fines five times more frequently than when it takes place close to Black or Hispanic ones. This racial discrimination is not necessarily intentional on the part of the public authorities, even if it often is so. It is systemic: that is to say, it results from a logic that is partly independent of individual will. So what allowed the Warren County movement to reach such scale was its capacity to generalize, to hook a local demand on to a global injustice.

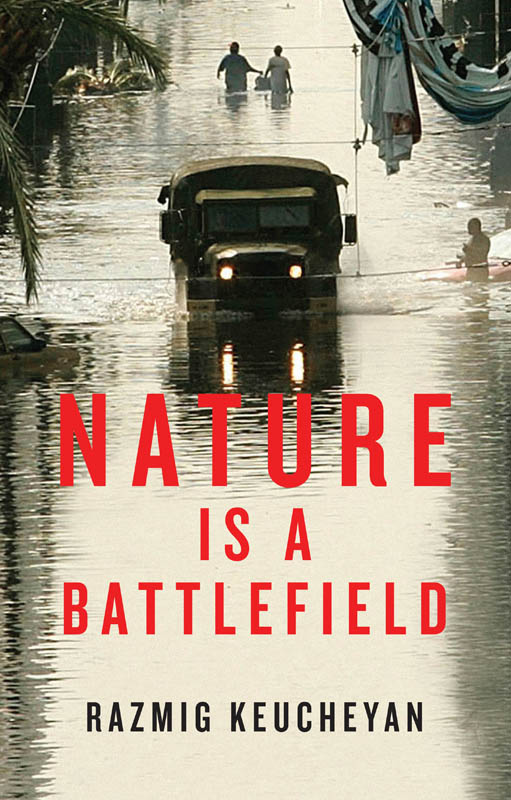

This episode is a marvellous illustration of this book's main argument: namely, that nature is a battlefield. Already today, it is a battlefield; and in future, as the ecological crisis deepens, it will increasingly become the theatre of conflicts among actors with divergent interests: social movements, states, armies, financial markets, insurers, international organizations In the Warren County case, the conflict resulted from a particular form of injustice, racism. But it could also follow from other types of inequalities. Nature is not somehow free of the power relations in society: rather, it is the most political of entities.

In approaching the ecological crisis in this manner, we are clashing with what is today a dominant view; indeed, a well-established consensus maintains that humanity has to overcome its divisions in order to solve the problem of environmental change. This consensus is driven by ecologist parties, many if not all of which emerged in the 1970s, based on the idea that the opposition between Left and Right was obsolete or now of only secondary importance. In France it is also promoted by civil society figures like Yann Arthus-Bertrand and Nicolas Hulot, and there are equivalent personalities in most countries. The ecological pact proposed by Nicolas Hulot a charter signed by several of the candidates for the 2007 French presidential election, as well as many thousands of citizens is typical of this conception of ecology. This consensus is also the backdrop to the dissatisfaction over the recurrent failure of international climate talks most recently in Copenhagen and Rio. Such complaints are a moral condemnation of states incapacity to come together over common environmental objectives.

There are more sophisticated versions of this ecological consensus. One of the leading theorists of postcolonialism and author of the classic

Next page