Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

2021 by Brenda Hess

Cover art: Andrey Yanushkov / Alamy Stock Photo and VolodymyrSanych / Shutterstock

Cover design: Daniel Urban-Brown

Interior design: Greta D. Sibley

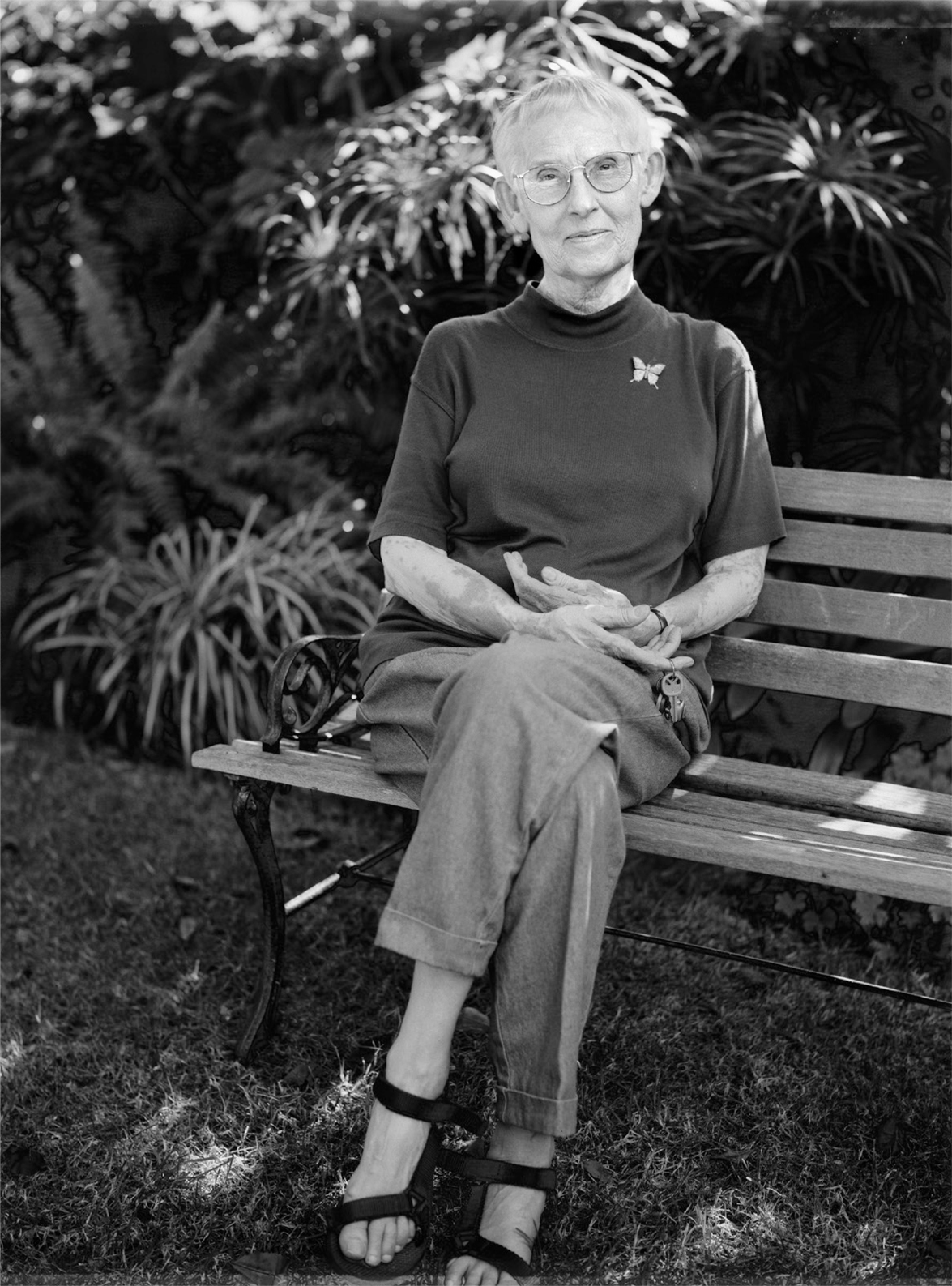

Frontispiece: Photo of Charlotte Joko Beck by Michael Lange

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For more information please visit www.shambhala.com.

Shambhala Publications is distributed worldwide by Penguin Random House, Inc., and its subsidiaries.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Beck, Charlotte Joko, author. | Hess, Brenda Beck, editor.

Title: Ordinary wonder: Zen life and practice / Charlotte Joko Beck; edited by Brenda Beck Hess.

Description: First edition. | Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala, [2021]

Identifiers: LCCN 2020033945 | ISBN 9781611808773 (trade paperback)

eISBN 9780834843707

Subjects: LCSH : Religious lifeZen Buddhism.

Classification: LCC BQ 9286.2 . B 445 2021 | DDC 294.3/444dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020033945

a_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

by Jan Chozen Bays

CHARLOTTE JOKO BECK was a unique person. Somehow, this middle-aged secretary became a daring innovator, a person who was always on the front lines when it came to trying new ways to be physically and mentally healthy. I was among the group of younger students at the Zen Center of Los Angeles who followed her lead.

She took the EST training with Werner Erhard, so dozens of people at the Zen Center took the EST training. She bought a small trampoline, and you could look up at the second-story window of her apartment at night and see her head appearing and disappearing as she bounced. Others began bouncing to improve lymph flow. She began race-walking with weights on, so many people took to striding the streets. Much later in life, because she didnt want to be a burden on the center as she aged, she took up Pilates, with a professional machine and a personal trainer, at a time when no one had heard of Pilates. She was eighty. When I saw her during this time, I was amazed that she seemed to have reversed aging, walking with more grace and talking with more clarity than she had before. She taught into her nineties.

I met her when she was an administrator in the Chemistry Department at University of California, San Diego. I think she actually ran that department of quirky professors from her desk. She related that when her boss was out of the office, people would line up to talk with her. She later said, I learned a lot about how to do therapy in those years. She was a single mother of four, divorced from an abusive, mentally ill professor who came close to killing her. Only the chance appearance of a neighbor saved her life. These experiences made her blessedly impervious to her students whining about their life problems, and made her very clear about what really mattered.

Joko became interested in Zen while attending a debate between a Zen master and a Christian minister. She was so impressed by the complete aplomb and palpable presence of the Zen teacher, Maezumi Roshi (Maezumi Sensei, at the time), that she began studying with him. She was then in her late forties. A close personal friend had developed cancer. This woman had eight children and meditated in the little room with her washer and dryer, the only place she could get any quiet. Joko was inspired by her friends devotion to practiceespecially her ongoing commitment to caring for those around her, even during her last days. Joko felt that her friends meditation practice was manifested in her refusal to take narcotics so her mind would remain clear, even in her very peaceful death. She sat with her friend as she made the transition from this life, becoming pure radiance. Joko was deeply moved by this experience, walking along the beach for hours afterward, aware that she had lost all fear of death.

She joined a meditation group in San Diego. Over the years, as the group evolved, others in her life began to attend as well, including several scientists and graduate students from the university. She was a determined student and began doing annual sesshin (a rigorous sitting meditation retreat) with Yasutani Roshi and Soen Roshi. Her daughters went to these intensive Zen retreats with her to spend timealbeit in silencewith their mother. After Maezumi Roshi opened his own center, she began driving two hours north each Saturday to the Zen Center of Los Angeles for dokusan (private interview) with him, and then driving two hours back home. Eventually, she retired and moved to the Zen Center to practice full time.

One by one, we followed her north and created a lively Zen community, a strange hybrid of a hippie commune and a Zen monastery, filled with young people hell-bent on enlightenment. Once again, people lined up in the hallway outside her apartment, waiting to talk with her. She said that although she was unorthodox in her approach to practice, Maezumi Roshi made her a teacher because he saw how students were naturally attracted to her. Jokos relentless focus on practice was infectious, and many people who practiced with her in San Diego and Los Angeles eventually became Zen teachers with centers of their own.

Joko became ordained and soon received Dharma transmission, becoming a much-beloved teacher. After six years of living and training at the Zen Center, issues of misconduct by Maezumi Roshi caused Joko to break her ties with him. She moved back to San Diego, where she founded the Ordinary Mind Zen School. Her way of teaching was direct, insightful, deceptively simple, and matter-of-fact, sometimes wry. You might wince when she pointed something out, but you knew shed hit the bulls-eyesome cherished core belief that was causing you suffering.

Joko was the first person I heard giving practical instructions in what we now call mindfulnesscurrently all the rage. She told us, When you wash the dishes, just wash the dishes. Feel the warmth of the water, the slipperiness of the soap, the plate in your hand. She could turn Zen rituals into everyday practices. In this book, she describes adapting the Zen practice of kinhin (slow walking between long periods of seated meditation) by telling an exhausted doctor to walk mindfully down a hallway each day, and his discovery of the refreshment this brought to his body and mind.

In a sesshin with Yasutani Roshi, Joko had a first opening into what she called real life. She described it as horrible. A friend remembers that afterward, when they took walks to talk about Zen, Joko would often stare intensely, point her finger and say, This is not real. In another sesshin, she had an opening into the emptiness of all things. It made her furious. She went to dokusan, yelled that everything was empty, and threw a small lamp at the Roshi. She related, Like a good Zen teacher, he ducked, said, Get used to it, and rang his handbell to dismiss me.