The Call of Bilal

ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION AND MUSLIM NETWORKS

Carl W. Ernst and Bruce B. Lawrence, editors

Highlighting themes with historical as well as contemporary significance, Islamic Civilization and Muslim Networks features works that explore Islamic societies and Muslim peoples from a fresh perspective, drawing on new interpretive frameworks or theoretical strategies in a variety of disciplines. Special emphasis is given to systems of exchange that have promoted the creation and development of Islamic identitiescultural, religious, or geopolitical. The series spans all periods and regions of Islamic civilization.

A complete list of titles published in this series appears at the end of the book.

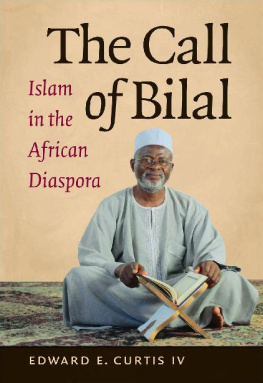

The Call of Bilal

Islam in the African Diaspora

Edward E. Curtis IV

The University of North Carolina Press

Chapel Hill

This book was published with the assistance of the Anniversary Endowment Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2014 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Set in Charis by codeMantra, Inc.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Cover illustration: Sheik Abdul Hameed Ahmad, Bahia, Brazil, 2013. Photograph by Renato Brito Semanovschi.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Curtis, Edward E., 1970

The call of Bilal : Islam in the African diaspora / Edward E. Curtis IV.

pages cm. (Islamic civilization and Muslim networks)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4696-1811-1 (pbk : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4696-1812-8 (ebook)

1. IslamAfrica. 2. African diaspora. 3. MuslimsNon-Islamic countries.

4. Bilal ibn Rabah. I. Title.

BP64.A1C87 2014

297.08996dc23

2014013130

18 17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

For my daughter, Alia May

Contents

Illustrations

Shrine of Bilal in Jordan,

A male leader summons spirits that possess the bodies of female dancers, Bizerte, Tunisia, 2008,

Cover of Poetic Pilgrimages CD The Starwomen Mixtape (2010),

Sidi Malang Mohamad blesses a woman, Kapalsadi village, Bharuch district, Gujarat, India, February 2004,

Jamaat al-Muslimeen leader Yasin Abu Bakr surrenders to Trinidad and Tobago authorities on August 1, 1990,

Nation of Islam rally, 1964,

Acknowledgments

Let me begin by expressing my appreciation for the projects research associate and my friend Jeremy Rehwaldt. Before I sat down to write the books first draft, I tested out ideas and talked them through with Jeremy. Our collaborative process provided me with immediate feedback and, just as important, helped me avoid the absolute isolation that, at least for me, actually makes writing harder. In addition to being my conversation partner, Jeremy researched and drafted sections of the chapter on African-descended Muslims in Europe. Finally, Jeremy copyedited the manuscript before I submitted it to the University of North Carolina Press.

I am grateful to Sylvester Johnson, who read this manuscript in a couple of different forms, schooled me on some things that I had not adequately addressed, and inspired me to pursue the project. Sylvester, with whom I cofounded the Journal of Africana Religions , is one of the most supportive, brilliant, and helpful colleagues that I have ever known. No one familiar with Sylvester and his work will be surprised by these remarks since he collaborates with many others to pursue pathbreaking projects in Africana and religious studies. I am lucky to work with and learn from him.

I thank the many institutions that made it possible for me to do my research and to write the book. First and foremost, thanks go to my supportive academic home, the Indiana University School of Liberal Arts in Indianapolis. As holder of the Millennium Chair of the Liberal Arts, I have been able to maintain a strong research agenda while being rewarded for my efforts to engage community members and the broader public in my work. I so appreciate being a part of this community. Financial support for the project also came from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, which funded a years research leave from 2008 to 2009. The work that I did that year on the transnational history of Islam in the United States informed and inspired this current project. Much of the actual writing of The Call of Bilal was supported by a regular sabbatical granted by my school and by a grant from the IU New Frontiers in the Arts and Humanities program. Of course, none of these parties is responsible for what I have written.

I tested out ideas from the book in various venues, and I thank audiences at Indiana UniversityPurdue University Indianapolis, the American Academy of Religion, and the Association for the Study of the Worldwide African Diaspora for those opportunities. A portion of my chapter on black Muslims in North Africa and the Middle East appeared in The Ghawarna of Jordan, Journal of Islamic Law and Culture 13, nos. 23 (2011): 193209, and I am happy to acknowledge the journal for permission to use that material here. The article was the product of my research in the southern Jordan Valley, and many people and institutions made it possible, especially the American Center of Oriental Research, Barbara Porter, Jean Bradbury, Hani Elayyan, Sarah Harpending, Nofeh Nawasra, Ana Silkatcheva, Rabee Zureikat, and residents of Ghor al-Mazraa and Ghor el-Safi.

Several colleagues were willing to write letters of support for this project; thanks go to Judith Weisenfeld, Ebrahim Moosa, Carl Ernst, Stephen Angell, and my dean, William Blomquist. Other colleagues went out of their way to provide helpful feedback, answer my questions, or support my research in other ways. Robert Rozehnal responded to my chapter on Siddi and Habshi Muslims in Pakistan and India with important questions and suggestions for improvement. Pashington Obeng answered additional questions about their religious lives in rural Karnataka via e-mail and phone and even contacted some of his informants on my behalf. Mauro Van Aken talked to me about his research in the Jordan Valley, giving me additional insight into the sociology of the dabka , or line dance. As usual, members of the American Academy of Religions Study of Islam Section e-mail subscription list came to my aid with bibliographical information. When it came time to publish the book, I received wonderful guidance from those colleagues who reviewed the manuscript anonymously. My departmental colleague Kelly Hayes shared a helpful critique of an early version of chapter 2. Another departmental colleague, David Craig, was always willing to listen to me and give me support, and my chair, Peter Thuesen, did the same while also writing on behalf of the project.

I am grateful that I had the opportunity to work once again with my editor, Elaine Maisner, and with Alison Shay, Paula Wald, and the entire staff of UNC Press. Julie Bush improved the book with her splendid, meticulous copyediting. And in Indianapolis, departmental staff member Debbie Dale offered both good cheer and lots of administrative assistance with the various business-related components of the project.

People from all over the African diaspora helped me obtain the illustrations for the book. Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy generously supplied the photograph of Sidi Malang Mohamad blessing a woman in Gujarat, India. Richard Jankowsky put me in touch with Matthieu Hagene, who shared a photograph of a Stambali ceremony in Tunisia. Muneera Rashida and Sukina Abdul Noor, the members of Poetic Pilgrimage, let me reprint their Starwomen Mixtape cover. Judy Raymond and Mark Lyndersay gave me the image of Yasin Abu Bakr surrendering to Trinidad and Tobago authorities. Joo Jos Reis located a photograph of Nigerian-born Shaykh Abdul Hameed Ahmad, a Muslim religious leader in Bahia, Brazil.