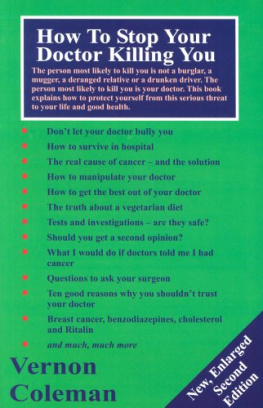

This book is copyright. Enquiries should be addressed to the author.

Copyright Vernon Coleman 1985, 1998 First published 1985 by Robert Hale. Subsequent editions published by the European Medical Journal.

The right of Vernon Coleman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The author Vernon Coleman MB ChB DSc is a registered medical practitioner. He is the author of over 100 other books, many of which are available as Kindle books on Amazon. For a list of books please see Vernon Colemans author page on Amazon or visit http://www.vernoncoleman.com/

Chapter 1: Medicine in Perspective

The influences and effects of historical events Myths and prejudices as they affect the historian The effects of medicine on such disciplines as agriculture and politics To understand the present we need to know the past

In the past, medical history has usually been studied by medical historians and written about for the benefit of other academics with the same specific interest. This book is different in that I am not a medical historian and I have not tried to write a book for specialists.

My interest is much more in the present than in the past and in studying and describing the cause and effect of discoveries and events rather than in recording the minutiae surrounding them. I believe that, although lists of dates and details may provide a superficial impression of history, real medical history must consist of an account of the influences which have led to major discoveries and of the effects which those discoveries have had upon society. It seems to me that such an approach should interest a much wider readership.

My interest in cause and effect does not, of course, mean that I have been prepared to abandon factual accuracy. Indeed, on the contrary, it is particularly important to ensure that all names, dates, places and specific discoveries are detailed as accurately as possible when conclusions and analyses are to be based on those facts.

My aims have meant that I have had to look for the truth rather than the myths, legends, fantasies and misconceptions with which many history books are so richly decorated. Many characters who play an important part in Roman and Greek history, to mention just two specific eras when myths were part of daily life, probably never existed. Voltaire wrote that history is but a fable that has been agreed upon, and you do not have to read many history books to see what he meant. To illustrate and support their own theories and contentions, many authors introduce and use suppositions and poorly documented hearsay evidence. I have tried to eliminate these myths and misconceptions except where they themselves had an influence on medical care or social progress.

I have also had to be on the lookout for prejudice and bias, and one of my most difficult tasks was to try to recognise and limit as far as possible my own prejudices and those of the authors from whose works I sought information. The importance of bias is easy to underestimate but an experienced historian can make any event appear both inevitable and foreseeable. It is dangerously easy to look for and discover links between otherwise isolated facts if you are struggling to support a theory in which you have more than a passing interest

Myths and bias are just two potential sources of inaccuracy. There are others. For example, much information reported as historical fact has to be regarded with suspicion when one realises that attitudes, knowledge and even language have changed over the centuries. These changes mean that reported material published ten centuries ago does not necessarily mean what it seems to mean today. The word plague is used today to describe a specific disorder with well-recognised symptoms, but over the centuries the word has been applied to almost all of the diseases which have puzzled sufferers and observers just as the word flu is today used to describe a wide variety of viral diseases which have certain vague, poorly defined symptoms. Similarly, the word leprosy has been frequently misused and an individual said to have had leprosy might have had any one of several diseases including syphilis, bubonic plague or smallpox or he might simply have been dirty, verminous or infirm.

Cynicism and suspicion are, I discovered, necessary qualifications for anyone writing a history book. I found, for example, that things do not happen quite as neatly and as suddenly as they might appear to do. There is not, of course, any sudden discovery which enables men to understand the working of the heart. What happens is that a number of isolated and, at the time, unrelated events result in a gradual increase in knowledge and understanding. Discoveries and inventions have very rarely had any immediate effect on ordinary life; rather they have been turning points or landmarks which have signalled a slow change in the direction in which thinking men have moved.

Another widely held misconception is that progress in medical care has been made by medical professions. The truth is that much progress in medicine has been made by people outside the mainstream of medical thought and practice. The contributions made by laymen include such specific innovations as the introduction of X-rays and such general contributions as the improvement of water supplies and sewerage facilities. Traditionally, medical history books have linked medical history to the medical profession and the acquisition and accumulation of medical knowledge, but improvements in health and reductions in mortality rates are related to far more than the origins of the Royal College of Physicians and the discovery of cellular pathology.

The truth is that the medical establishment has not always been right and the quacks have not always been wrong. Thinkers reviled and rejected by those influenced too much by greed, stubbornness, stupidity, jealousy and religious or philosophical commitments have often been proved right by later events. For many centuries, members of the orthodox medical establishment provided care for only a small proportion of the total population. The majority of patients were looked after by informally trained midwives, medicine men, alchemists and apothecaries who together made formidable contributions to medical theory as well as medical practice.

Then there is the point that the role and influence of different treatments have been confused by the fact that the importance of the placebo effect has been easy to underestimate. For more than seven hundred years the kings of England and France were regarded by their subjects as able to cure physical illness simply by touch, and evidence of this faith survived in France until the reign of Louis XVI and in England until Queen Anne. Many other healers, who relied on pure belief and effectively acted as mediums for real or imaginary supernatural forces, have been able to influence the progress of disease significantly. The interlinking relationship between mental state and physical illness is now known to be a strong and important one but at the time when traditional treatments were in common use this relationship was not widely recognised and was often attributed to unworthy influences. Nevertheless, although today we can relate modern knowledge and thinking to conditions and influences at all times in history, it is important to remember that, placebo response or not, the result was genuine. The Kings Touch may have relied upon the placebo effect but it undoubtedly had real influence.

Another possible cause of confusion and error is the fact that history is a continuous, fluid process which cannot be divided into neat sections on either temporal or geographic grounds. Picking one area of medical care in the sixteenth century and describing it as typical of medicine at that time is as misleading as choosing an area of medical care today and claiming that general standards can be judged from that one example. The quality of care provided in a teaching hospital in London today is very different to the quality of care provided in an ordinary district hospital no more than a mile or two away.