Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

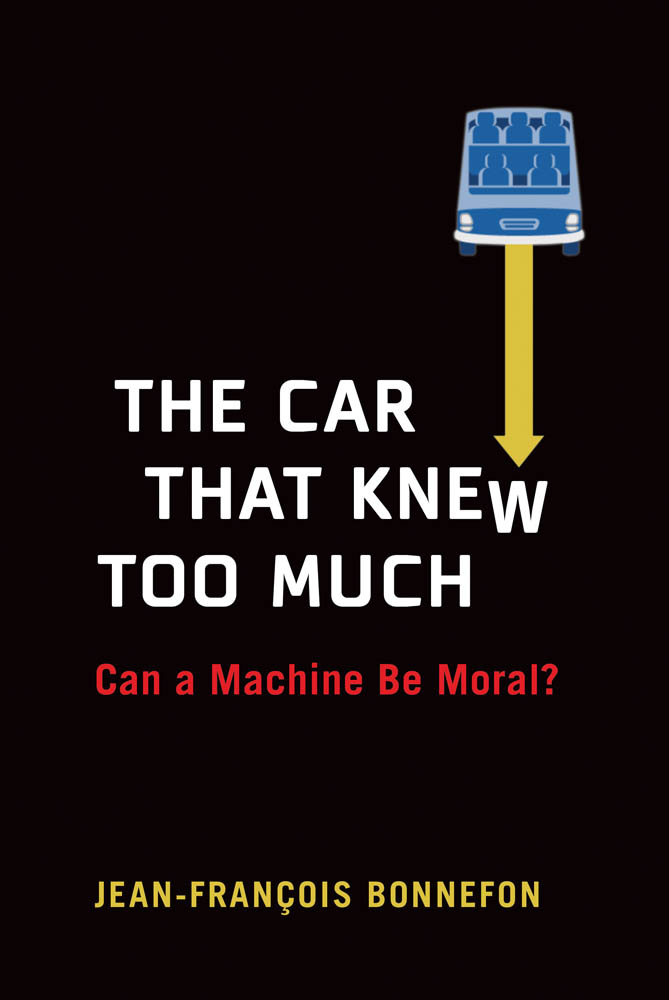

THE CAR THAT KNEW TOO MUCH

CAN A MACHINE BE MORAL?

JEAN-FRANOIS BONNEFON

THE MIT PRESSCAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTSLONDON, ENGLAND

This translation 2021 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Originally published as La voiture qui en savait trop, 2019 DITIONS HUMENSCIENCES / HUMENSIS

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bonnefon, Jean- Fran ois , author.

Title: The car that knew too much : can a machine be moral? / Jean- Fran ois Bonnefon.

Other titles: La voiture qui en savait trop. English

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2021] | Translation of: La voiture qui en savait trop : lintelligence artificielle a-t-elle une morale? | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020033735 | ISBN 9780262045797 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Automated vehicles--Moral and ethical aspects. | Automobiles--Safety measures--Public opinion. | Products liability--Automobiles. | Social surveys--Methodology.

Classification: LCC TL152.8 .B6613 2021 | DDC 174/.9363125--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020033735

d_r0

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

There was less than one year between the original French edition of this book and the English edition that you are about to readbut it was the year of the coronavirus pandemic. The pandemic threw into stark relief many of the themes of this book: How safe is safe enough? How do we decide between saved lives and financial losses? If we cannot save everyone, whom do we choose? Do we value the lives of children more? Do we value the lives of their grandparents less? Do people across different countries have different views in all these matters?

In this book, these moral questions are triggered by a momentous change in the way we drive. As long as humans have been steering cars, they have not needed to solve thorny moral dilemmas such as, Should I sacrifice myself by driving off a cliff if that could save the life of a little girl on the road? The answer has not been practically relevant because in all likelihood, things would happen way too fast in such a scenario for anyone to stick to what they had decided they would doits a bit like asking yourself ,Should I decide to dodge a bullet if I knew it would then hit someone else? But as soon as we give control of driving to the car itself, we have to think of these unlikely scenarios because the car decides faster than us, and it will do what we told it to do. We may want to throw our hands in the air, say that these moral questions cannot be solved, that we do not want to think about them, but that will not make them go away. The car will do what we told it to do, and so we need to tell it something. We need to consider whether the car can risk the life of its own passengers to save a group of pedestrians, we need to consider if it should always try to save children first, and we even need to consider if it is allowed to cause unlimited amounts of financial damage to save just one human life.

In March 2020, it became clear to leaders in several European countries that if the coronavirus epidemic went unchecked, hospitals would soon run out of ventilators to keep alive the patients who could not breathe on their own during the most severe stage of the disease. And if that happened, health care workers would have to make very hard decisions about which patients they should save and which patients they would let die, at a scale never seen before, under the spotlight of public opinion, at a moment when emotions ran very high. To avoid such a disastrous outcome, drastic measures were taken to slow down the epidemic and to vastly increase the number of available ventilators. In other words, rather than solving a terrible moral dilemma (Who do we save if we cannot give everyone a ventilator?), everything was done so that the dilemma would not materialize.

Now think of self-driving cars. One of the biggest arguments for self-driving cars is that they could make the road safer. Lets assume they can. Still, they cannot make the road totally safe, so accidents will continue to happen and some road users will continue to die. Now the moral dilemma is, If we cannot eliminate all accidents, which accidents do we want to prioritize for elimination?, or perhaps, If it is unavoidable that some road users will die, which road users should they be? These are hard questions, and it will take this whole book to carefully unpack them (there will be a lot of fast-paced scientific action, too). But could we avoid them entirely? Remember that in the coronavirus case, the solution was to do everything possible to not have to solve the dilemma, by preventing it from materializing. In the case of self-driving cars, preventing the dilemma means one of two things: either we simply give up on these cars and continue driving ourselves, or we dont put them on the road until we are sure that their use will totally eliminate all accidents. As we will see, there are moral arguments against these two solutions because this whole situation is that complicated.

As a psychologist, I am always more interested in what people think about something than in the thing itself. Accordingly, this book is chiefly concerned with what people think should be done about self-driving cars. And because the moral issues with self-driving cars are pretty complex, it turns out to be quite complicated to measure what people think about them. So complicated, in fact, that my teammates and I had to imagine a different way to do social science research, and we created a brand new sort of beast: Moral Machine, a viral experiment. As you are reading this, it is likely that more than ten million people all over the world have taken part in that experiment. This number is insaneno one has ever polled ten million people before. You will see, though, that to obtain this kind of result, we had to take unusual steps. For example, we had to give up on things that are usually desirable, like keeping our sample representative of the worlds population in terms of age, gender, education, and so on. This made our work more difficult when the time came to analyze our data, but I hope youll agree that it was worth it. Indeed, this book will take you backstage and tell you the whole story of how Moral Machine was born and how it grew into something we never expected. So buckle up, and enjoy the ride.

Toulouse, France, June 2020