Also by Antonio Damasio

The Strange Order of Things

Self Comes to Mind

Looking for Spinoza

The Feeling of What Happens

Descartes Error

Copyright 2021 by Antonio Damasio

Illustrations copyright 2021 by Hanna Damasio

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Harvard University Press for permission to reprint an excerpt of The brain is wider than the sky from The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition, edited by Ralph W. Franklin, Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Copyright 1998 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College, Copyright 1951, 1955 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College, copyright renewed 1979, 1983 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright 1914, 1918, 1919, 1924, 1929, 1930, 1932, 1935, 1937, 1942 by Martha Dickinson Bianchi. Copyright 1952, 1957, 1958, 1963, 1965 by Mary L. Hampson.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Damasio, Antonio R., author. Damasio, Hanna, illustrator.

Title: Feeling & knowing : making minds conscious / Antonio Damasio ; illustrations by Hanna Damasio.

Description: First edition. New York : Pantheon Books, 2021. Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020034554 (print). LCCN 2020034555 (ebook).

ISBN 9781524747558 (hardcover). ISBN 9781524747565 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Consciousness.

Classification: LCC BF311 .D3233 2021 (print) | LCC BF311 (ebook) | DDC 153dc23

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020034554

LC ebook record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020034555

Ebook ISBN9781524747565

www.pantheonbooks.com

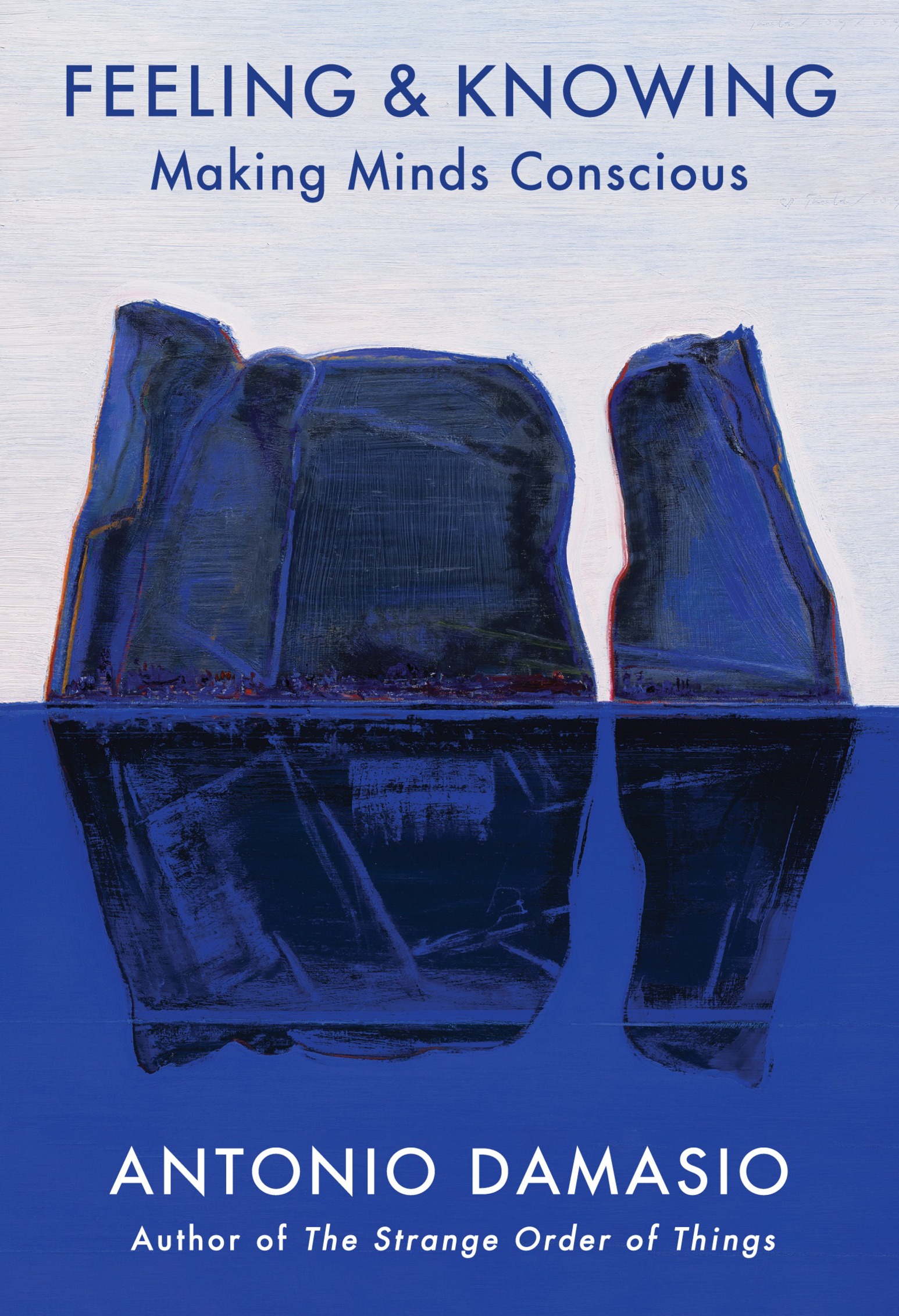

Cover image: Rock Island Split 2019 by Wayne Thiebaud. 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. Photo courtesy Acquavella Galleries.

Cover design by Kelly Blair

ep_prh_5.8.0_c0_r0

For Hanna

The life of a play begins and ends

in the moment of performance.

Peter Brook

Contents

1

The book you are about to read has some curious origins. It owes a lot to a privilege I have long enjoyed and a frustration I have often felt. The privilege consists in having had the luxury of space when I needed to explain complicated scientific ideas using the large number of pages of a standard nonfiction book. The frustration came from talking to many of my readers, over the years, and learning that some ideas that I wrote about with enthusiasmand that I had been keenest to have readers discover and enjoywere lost in the middle of long discussions and hardly noticed, let alone enjoyed. My private response, on such occasions, has been a firm but always postponed decision: to write only about the ideas I most care for and leave behind the connective tissue and the scaffolding meant to frame them. In brief, do what good poets and sculptors do so well: chip away at the nonessential and then chip some more; practice the art of haiku.

When Dan Frank, my editor at Pantheon, told me that I should write a focused and very brief book on consciousness, he could not have anticipated a more receptive and enthusiastic author. The book you have in your hands is not exactly what he ordered, because it is not only about consciousness, but it comes close. What I could not have anticipated is that the effort of reconsidering and paring down so much material, would help me confront facts that I had overlooked and develop new insights about not just consciousness but related processes. The road to discovery is twisted, to say the least.

It is not possible to make sense of what consciousness is and of how it developed without first addressing a number of important questions in the universe of biology, psychology, and neuroscience.

The first of those questions concerns intelligences and minds. We know that the most numerous living organisms on earth are unicellular, such as bacteria. Are they intelligent? Indeed they are, remarkably so. Do they have minds? No, they do not, I believe, and neither do they have consciousness. They are autonomous creatures; they clearly have a form of cognition relative to their environment, and yet, instead of depending on minds and consciousness, they rely on non-explicit competencesbased on molecular and sub-molecular processesthat govern their lives efficiently according to the dictates of homeostasis.

And what about humans? Do we have minds and only minds? The simple answer is no. We certainly have minds, populated by patterned sensory representations called images, and we also have the non-explicit competences that serve simpler organisms so well. We are governed by two types of intelligence, relying on two kinds of cognition. The first is the one humans have long studied and cherished. It is based on reasoning and creativity and depends on the manipulation of explicit patterns of information known as images. The second type is the non-explicit competence found in bacteria, the one variety of intelligence on which most lives on earth have depended and continue to depend. It remains hidden to mental inspection.

The second question we need to address deals with the ability to feel. How are we able to feel pleasure and pain, well-being and sickness, happiness and sadness? The traditional answer is well known: the brain allows us to feel, and all we need is to investigate the specific mechanisms behind specific feelings. My aim, however, is not to elucidate the chemical or neural correlates of one particular feeling or another, an important issue that neurobiology has been attempting to address with some success. My aim is different. I wish to know about the functional mechanisms that allow us to experience in mind a process that clearly takes place in the physical realm of the body. That intriguing pirouettefrom physical body to mental experienceis conventionally attributed to the good offices of the brain, specifically to the activity of physical and chemical devices called neurons. Although it is apparent that the nervous system is required to accomplish that remarkable transition, there is no evidence that it does soalone. Moreover, the intriguing pirouette that allows the physical body to harbor mental experiences is regarded by many as impossible to explain.

In an attempt to answer the critical question, I focus on two observations. One of them relates to the unique anatomical and functional features of the interoceptive nervous systemthe system responsible for signaling from the body to the brain. These features are radically different from those that can be found in other sensory channels, and although some of them have previously been documented, their significance has been overlooked. And yet they help explain the peculiar melding of body signals and neural signals that decisively contributes to experiencing the flesh.