Helen Frisby - Traditions of Death and Burial

Here you can read online Helen Frisby - Traditions of Death and Burial full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Traditions of Death and Burial

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Traditions of Death and Burial: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Traditions of Death and Burial" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Traditions of Death and Burial — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Traditions of Death and Burial" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

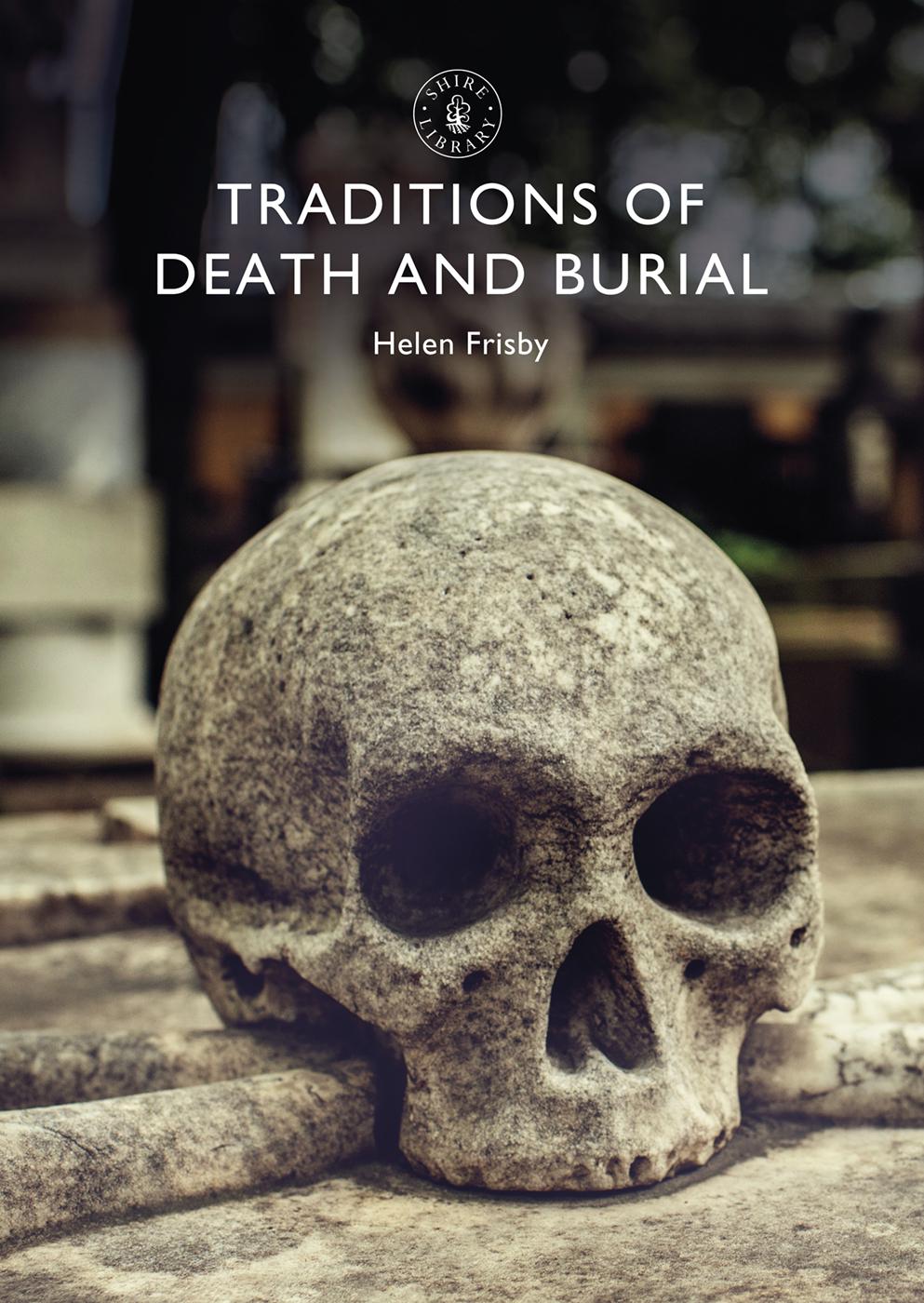

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

W ERE ALL GOING to die; but its become the great unmentionable. Despite the physical comforts of modern Western life, the process of dying has somehow become socially, spiritually and emotionally impoverished. This book will explore how ordinary English people since the Middle Ages onwards have faced up to the inevitable, and what we might be able to learn from the past about dealing with d eath and dying.

In particular this book explores how, through the medium of custom and tradition, relationships between the living, the dying and dead have been shaped and reshaped over the last millennium. In some cases, the outward form of these customs and traditions has changed dramatically over time, reflecting changes in society, culture and technology. That said, there are also certain funeral customs and traditions which have changed little, and which our medieval ancestors might well recognise. And (nearly) always, echoing down the centuries to the present day and looking ahead to the future, there has been that powerful underlying need for connection with the dead loved and hated ones to be sure, but also our own futu re dead selves.

There is one brief but significant exception to this. By the 1990s the impact of two World Wars, followed by a half-century of particularly fast, deep social and cultural change, seemed finally to have severed relations between the world of the living and that of the dead. The dead, however, are patient. Indeed, it was just as the late-twentieth-century death taboo appeared most firmly established, that new funeral customs and traditions were already emerging. Furthermore, many of these new ritualisations of death, as they are often called by academics who study the history of funerals, often turn out under closer examination to be modern twists upon centuries-old, tried and tested c ustomary forms.

This story of how the English have related or not to their dead over almost a millennium is told here in five chronological chapters. The second chapter covers the period from c .1066 to 1500, during which relationships between the living and the dead were driven by high and sudden patterns of mortality. Through an entire raft of popular customs and beliefs, the living could gain both emotional satisfaction and social status by assisting the dead in their post-mortem journeys through Purgatory. In the process one could also gather spiritual credit to ameliorate ones own future progress when the time came.

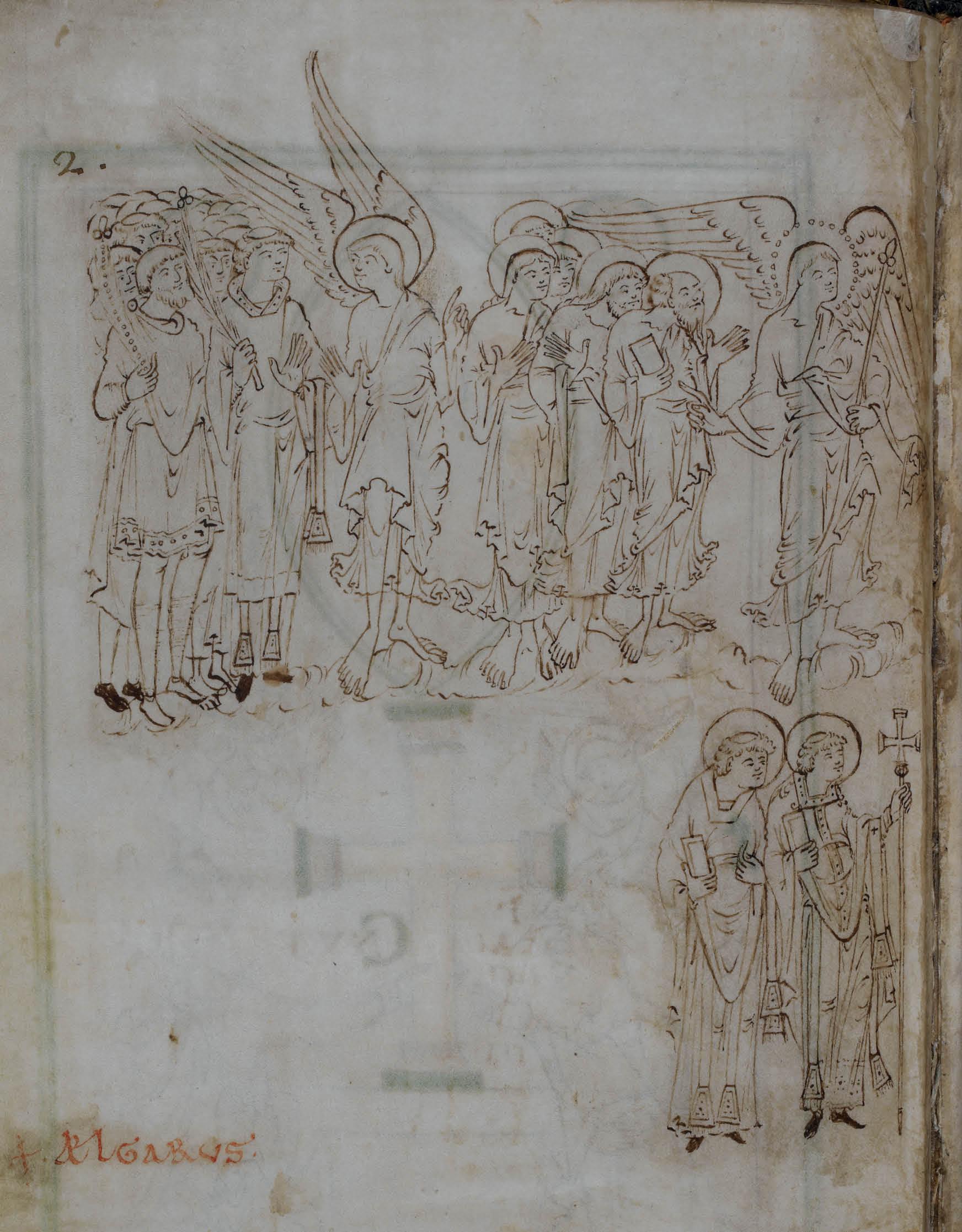

Angels conduct the spirits of benefactors into Heaven, the portal of which is opened by St Peter for their reception, while below, two saints watch a contest between St Peter and Satan for a soul at the Last Judgement. Both images extend across two pages of the New Minster Liber Vitae.

High and sudden mortality also characterised the early modern period ( c . 15001750 ), which is the subject of the third chapter. The official abolition of Purgatory by Protestant reformers undoubtedly impacted the nature and extent of relationships between the living and the dead. However, other evidence gathered by antiquarian and folklore collectors of the time points us toward a complex story of public conformity, yet also private resistance to change in this regard. The latter part of this period saw social and technological changes including the rise of the middle classes and beginnings of modern medicine, which would later come greatly to reshape the pr ocess of dying.

Fifteenth-century Doom painting in Holy Trinity Church, Coventry. At a time when death often came suddenly, and few could read, such vivid depictions of the after-life reminded people to be prepared for death at all times.

It was during the next, industrial period (fourth chapter, c . 17501900 ) that modern, urban consumer culture really began to influence English deathways. That said, not only did the older notion of connectedness with the dead persist in popular custom, but the products of modern mass manufacture themselves became imbued with the magical ability to assist and relate to the dead. Again, the story of death in English custom and tradition is complicated and of ten surprising.

Despite the death toll of the 191418 Great War, as recounted in the fifth chapter ( c . 19002000 ) many Victorian and older funeral customs and beliefs could still be found in England well into the inter-war period. The introduction of the Chapel of Rest during the 1930s would, however, prove a key development. Along with the arrival of the motor hearse around the same time, this eventually rendered many previous funerary customs redundant. This willing abandonment of tradition in favour of practical convenience highlights an important point: that many of the older customs had been emotionally and financially burdensome, not to mention socially intrusive and physically unpleasant. This reminds us that the line between history and mere nostalgia is a fine, but important one when it comes to death and funeral traditions. The decades following the Second World War would see the ascendancy of this kind of practical death as rapid social changes especially in the role and position of women took effect.

Almost a quarter of the way through the twenty-first century, however, and its clear that dying has life in it yet. For most British people, death nowadays is the predictable conclusion of a long life although modern lifestyle habits may be changing this. When it does eventually come, twenty-first-century death is usually caused by the chronic diseases of extreme old age. Arguably this kind of death presents its own social, emotional and spiritual challenges, meaning that the need for funeral customs and traditions remains as powerful as ever. Perhaps we will only stop needing to relate to the dead if and when we as a species finally achieve immortality at which point, it could be said, we cease anyw ay to be human.

Some of the historic and present-day customs and traditions discussed in the following chapters will seem so obvious and mundane as to be almost unworthy of comment; while others may feel alien, even shocking. All, I hope, will in their own way make you think and talk about what mortality means to you. Most of all, however, I hope that reading about and considering death in custom and tradition will encourage us all to think that little bit more about what it means to live.

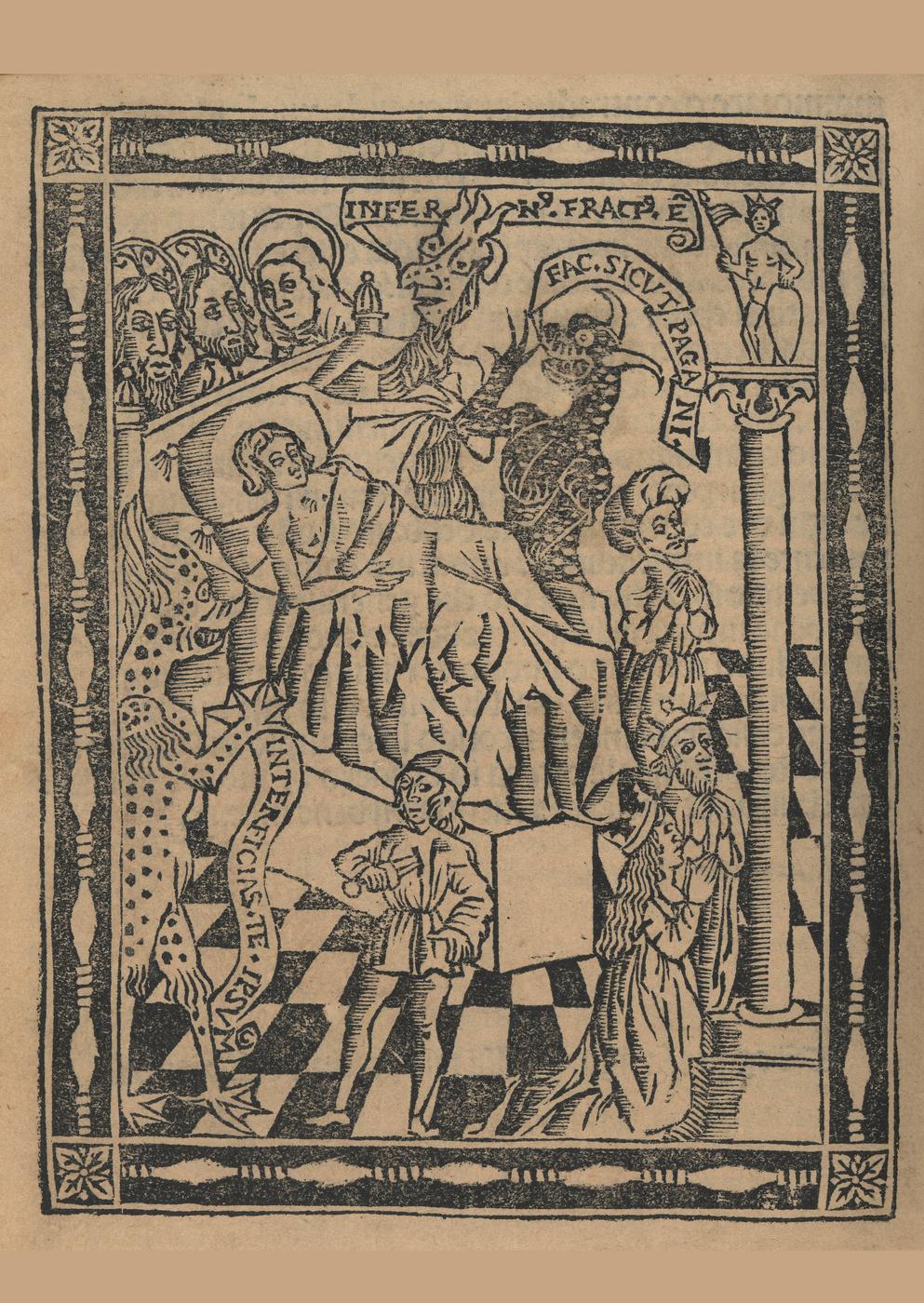

Ars Moriendi or, in this case, how not to die. This illustration ( c .1503) depicts a restless man on his deathbed, with looming demons ready to take his soul. Dying badly could undo the effect of a lifetime of good works, condemning a person to a difficult passage through Purgatory or even to Hell.

I F FUNERAL CUSTOMS and traditions emerge and endure because they get the deceased to where they need to go, and the bereaved where they need to be, then during the Middle Ages it was above all the Christian concept of Purgatory which afforded these needs ritual shape. The shadowy, fragmented nature of the evidence from the early part of this period in particular means that much remains unknowable concerning the specifics of what happened at the deathbed and afterwards. Where evidence does exist it often describes the customs and experiences of elite individuals rather than the common people, so a degree of inference must be made. However, we do know that by the mid-1200s there was established the general notion that the dead, their souls caught in the cosmic battle between good and evil, and facing the judgement of God himself, could and should be assisted on their way by the living. Underlying this was the idea, comforting and burdensome in doubtless equal measure, that the relationships between the dead and living might be enduring even be yond the grave.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Traditions of Death and Burial»

Look at similar books to Traditions of Death and Burial. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Traditions of Death and Burial and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.