Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress.

ISBN 9780197522011

eISBN 9780197522035

TABLE OF CONTENTS

For the transliteration of Arabic and Persian terms into English, I have adopted a highly simplified system. The Arabic letter ayn is represented as a forward-facing apostrophe (), while the hamza is represented as a backward-facing apostrophe (). No other special characters have been used, except for in the endnotes where books or articles that use them are cited. Arabic and Persian terms that appear in one or more of the standard English dictionaries (e.g. ulema), and proper names that are in wide use in English (e.g. Nasser, Khomeini), are written according to their common English spelling.

I n a book published in 1959, the Egyptian religious leader Mahmud Shaltut (18931963) attempted to define the basic elements of Islam: Islam, he wrote, is the religion of God (din Allah), who entrusted His teachings concerning His fundamental principles and His laws to the Prophet Muhammad and gave him the task of calling all people to it.

As Shaltuts definition indicates, Islam is first and foremost a religion, or what in Arabic is called a din: a way of believing in God and of organizing life around obedience to Him. The very word islam, an Arabic word literally meaning submission, originally denoted the act of giving oneself entirely and exclusively to God. Muslims, those who practise Islam, call this deity Allah, another Arabic word, which simply means God.

More specifically, Islam, like Judaism and Christianity, is a monotheistic religion. Allah, it teaches, is the one and only deity. The first half of the shahada, the Islamic testimony of faith, is la ilaha illa Allah, There is no god but Allah. The first and fundamental principle of Islamic belief is tawhid, the act of declaring Gods unity.

Islam is also, again like Judaism and Christianity, a scriptural religion. Its adherents revere a sacred and authoritative book called the Quran (literally, the recitation).

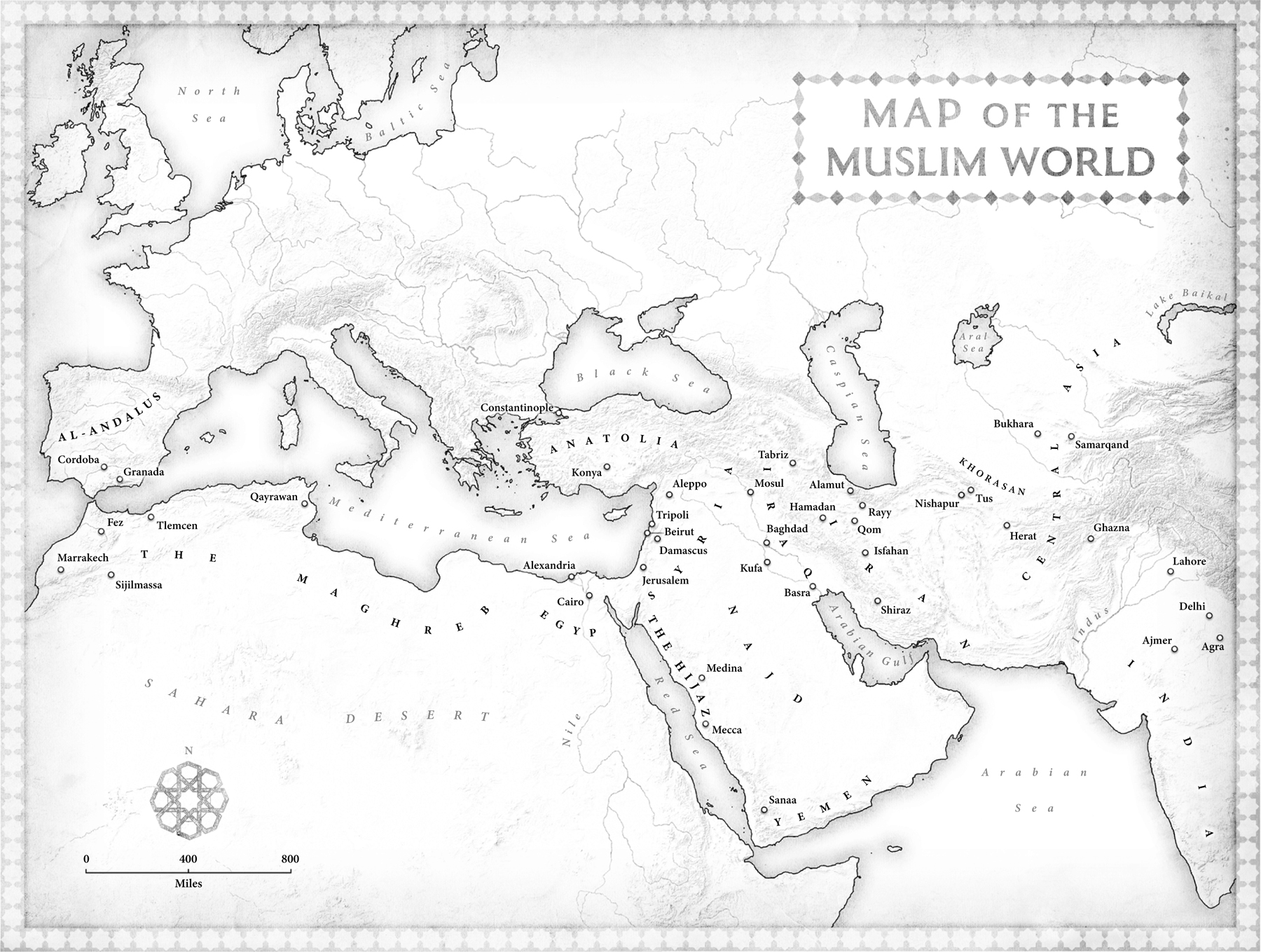

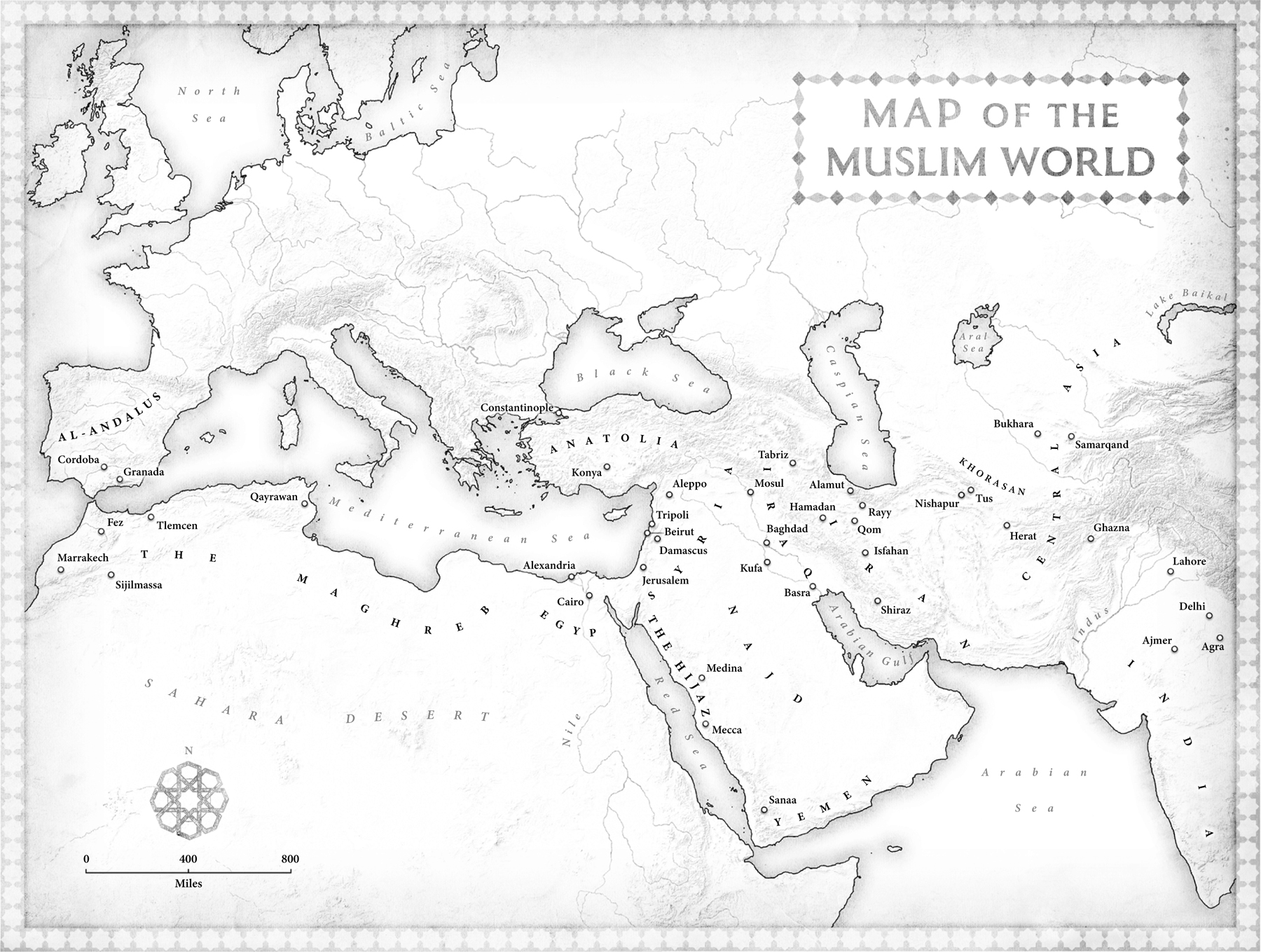

Islam is also an Arabic religion. Muhammad was a native of Mecca, in the Hijaz region of the Arabian Peninsula, and the scripture he received was in Arabic. Muslims regard Arabic as the language of Allah, pray in Arabic, and, for the first five centuries or so of Islamic history, used Arabic almost exclusively as the language of their religious writings, whatever their ethnic or linguistic background.

Despite the centrality of the Arabic language, however, Islam is also a universal religion, meaning that, like Christians, Muslims believe their religion to be valid for all times, peoples, and places. This idea is rooted in the notion that the Quran is perfect and complete, and Muhammad the best and final prophet sent to mankind, the implication being that only by following Muhammad and his message can a person fully serve the one God.

Islam is also (to borrow a phrase from the sociologist Max Weber) a this-worldly religion, concerned with giving order to the lives of individuals and communities in this world. The framework for this ordering of life is supplied by the Sharia, an Arabic word originally meaning the path to water, but used in Islamic thought to denote the law decreed by Allah. As we shall see, like the Halakha or Jewish law, this divine law is thought to extend to areas of life that a modern secular law wouldnt normally cover, like how to pray or what foods to avoid.

At the same time, Islam is also a salvific religion, concerned with the fate of human beings in the world-to-come. After belief in Gods unity and prophecy, the third fundamental principle of Islamic faith is the belief in the return (maad) to Allah after death.

Muslims have tended to read all of these ideas about their religion out of their scripture. As the Egyptian Quran scholar Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd (19432010) has written, Whatever issue emerges in the life of Muslim communities, the Quran is the first source to be consulted for a solution.

In the medieval (c.6001500) and early modern (c.15001800) periods, four such traditions legal theory (fiqh), Sufi mysticism (tasawwuf), revealed theology (kalam), and philosophy (falsafa) and two major denominations, Sunnism and Shiism, dominated Islamic thought. In modern times (c.1800present), other traditions like Islamic revivalism, modernism, and Salafism have come to the foreground. As we shall see, the interaction and competition between these traditions has helped set the course for the development of Islam. To understand Islam properly, we have to understand this history.

Yet why should we care about Islamic thought and its history? In a world where politics, power, and privilege are often thought to explain everything, studying the intellectual history of a religious faith may seem like something of a luxury. Nevertheless, we should care about Islamic thought. Here are three reasons why.

First and most fundamentally, Islamic thought, as the present book aims to show, is intrinsically fascinating. What serious and intelligent persons over many generations have held to be significant, the historian Marshall Hodgson once observed, rarely turns out, on close investigation, to be trivial. This is as true of serious and intelligent Muslims as of those of other faiths. Anyone interested in the history of ideas in the story of human responses to the big questions about God, man, and the world ought to take into account the Muslim contribution to that history.

Second, while the world may appear increasingly post-religious from the vantage point of Western Europe and North America, religion nevertheless remains a key fact of life for many, the key fact of life for countless people everywhere. This seems particularly true for those whose religion is Islam. Adherents of Islam number some 1.8 billion people about a quarter of the worlds population and can be found everywhere from Los Angeles to Jakarta. Whatever our own beliefs, engaging with our fellow human beings in a thoughtful way requires us to know something about the ideas that make them tick.