EVANGELICAL EXODUS

EVANGELICAL

EXODUS

Evangelical Seminarians

and

Their Paths to Rome

Edited by Douglas M. Beaumont

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Except where otherwise noted, Scripture citations are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible , Second Catholic Edition, 1965, 1966, and 2006 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. All rights reserved.

Excerpts from the English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church , Second Edition, 1994, 1997, 2000 by Libreria Editrice VaticanaUnited States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved.

Cover art:

The Calling of Andrew and Peter (fresco)

by Giusto di Giovanni de Menabuoi

Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

Photograph Bridgeman Images

Cover design by John Herreid

2016 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-62164-042-4 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-650-4 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2015942047

Printed in the United States of America

To the Dumb Ox:

May our speech one day approach the majesty of your silence.

Saint Thomas Aquinas,

pray for us.

In quibus natus sum,

a me rmovens tnebras,

pecctum sclicet et ignorntiam.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

From Historic Christianity

to the Christianity of History

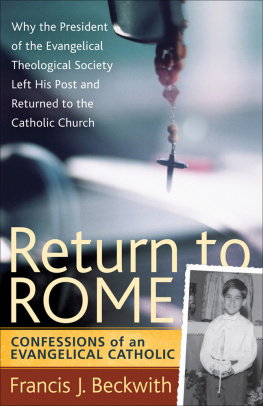

I remember distinctly the moment I knew that I had to return to the Catholic Church, in which I had been baptized and confirmed as a youngster. It was in mid-March 2007, only four months after I had been elected the fifty-eighth president of the Evangelical Theological Society, an academic society of about 4,200 members at the time. After decades of assimilating Catholic thought in my spiritual pilgrimage without realizing it, and with the help of some Catholic friends who posed to me just the right questions with just the right degree of gentle prodding, I had been brought to the outer bank of the Tiber. But what finally forced me to take my first steps on the bridge that traversed those seemingly foreboding waters was a passage authored by the renowned Reformed historical theologian Carl Trueman in his review of the book Is the Reformation Over ? In it Trueman writes:

Every year I tell my Reformation history class that Roman Catholicism is, at least in the West, the default position. Rome has a better claim to historical continuity and institutional unity than any Protestant denomination, let alone the strange hybrid that is Evangelicalism; in the light of these facts, therefore, we need good, solid reasons for not being Catholic; not being a Catholic should, in other words, be a positive act of will and commitment, something we need to get out of bed determined to do each and every day. It would seem, however, that... many who call themselves Evangelical really lack any good reason for such an act of will; and the obvious conclusion, therefore, should be that they do the decent thing and rejoin the Roman Catholic Church. I cannot go down that path myself, primarily because of my view of justification by faith and because of my ecclesiology; but those who reject the former and lack the latter have no real basis upon which to perpetuate what is, in effect, an act of schism on their part. For such, the Reformation is over; for me, the fat lady has yet to sing; in fact, I am not sure at this time that she has even left her dressing room.

After reading that paragraph, I felt as if I had been punched in the nose. I realized at that instant that I was in schism with the Catholic Church, and for that reason, the burden was on me and not on the Church to provide an account of my present state of noncommunion. At that moment, my Christian faith ceased to be something that I chose and became something that chose me. It was, as Doug Beaumont notes in his introduction to this wonderful collection, a paradigm shift, a radical reorientation of where one stands in relation to the universal Church. I no longer saw myself standing before an ecclesial buffet of fragmented Western Christendom, eagerly seeking to select those beliefs that conformed to my theological predilections. I found myself under a creed I did not invent rather than a confession that was under my control.

For those who have not taken this sort of journey, who have not ventured outside the confines of Evangelical culture, doctrine, and spirituality, the very idea of being at a crossroads with Catholicism seems almost counterintuitive. The contributors to this volume, including the author of this foreword, were at one time in that very same state of bewilderment when reports of friends and acquaintances drifting to Rome reached our eyes and ears. Why entertain Catholicism, we thought, when some of its essential beliefsespecially on matters over which Evangelical Protestants part ways with Catholicsare unbiblical and not part of historic Christianity? After all, as we were told by some of the leading lights of Evangelicalism, the Reformation had simply restored what had been believed by the ancient Church but had been corrupted by the Roman Communion of the Middle Ages. True Christianity was like a pristine ocean vessel that had over the years acquired all these Catholic barnacles that impeded the ship from smoothly reaching its eternal destination. In contrast, historic Christianity, as our Evangelical friends are fond of saying, consists of just a few basic doctrines, easily derived from the Churchs only authority, an inerrant Bible. All the other doctrines over which Christians disagreee.g., the nature of the sacraments, ecclesiology, womens ordination, the precise nature of the Incarnation, whether God is inside or outside time, whether one can lose ones salvationare either nonessential or, in the case of certain Catholic doctrines such as praying for the dead and to the saints, unbiblical.

What the contributors to this volume discovered in their journeys is that this narrative, though having sustained them for many years and having kept them from entertaining Catholicism, could not withstand the scrutiny of historical analysis. Speaking for myself, it was a jarring experience to learn that there were serious problems with the historic Christianity story I had uncritically believed for decades as an Evangelical Protestant. Take, for example, the use of the early Church Fathers in the work of Norman L. Geisler, the founder of Southern Evangelical Seminary, the institution that connects all the contributors to this book. In volume 3 of his Systematic Theology , Geisler argues that the Reformers understanding of the doctrine of justification can be found in the early Church Fathers. To make his case, he conscripts a few quotations from several of them, including these from the homilies of Saint John Chrysostom (ca. A.D. 344/354A.D. 407):

In order then that the greatness of the benefits bestowed may not raise you too high, observe how he brings you down: by grace you have been saved, says he, through faith; Then, that, on the other hand, our free will be not impaired, he adds also our part in the work, and yet again cancels it, and adds, And that not of ourselves.For this is [the righteousness] of God when we are justified not by works (in which case it were necessary that not a spot even should be found) but by grace, in which case all sin is done away.

These comments do indeed sound like what one would find in the sermons of a Calvin or a Luther. Yet, Saint John Chrysostom published many other homilies, two of which contain these words:

Let us then give them aid and perform commemoration for them. For if the children of Job were purged by the sacrifice of their father, why do you doubt that when we too offer for the departed, some consolation arises to them? [For] God is wont to grant the petitions of those who ask for others. And this Paul signified saying that in a manifold Person your gift toward us bestowed by many may be acknowledged with thanksgiving on your behalf (2 Cor 1:11). Let us not then be weary in giving aid to the departed, both by offering on their behalf and obtaining prayers for them: for the common Expiation of the world is even before us.Mourn for those who have died in wealth, and did not from their wealth think of any solace for their soul, who had power to wash away their sins and would not. Let us all weep for these in private and in public, but with propriety, with gravity, not so as to make exhibitions of ourselves; let us weep for these, not one day, or two, but all our life. Such tears spring not from senseless passion, but from true affection. The other sort are of senseless passion. For this cause they are quickly quenched, whereas if they spring from the fear of God, they always abide with us. Let us weep for these; let us assist them according to our power; let us think of some assistance for them, small though it be, yet still let us assist them. How and in what way? By praying and entreating others to make prayers for them, by continually giving to the poor on their behalf.

Next page