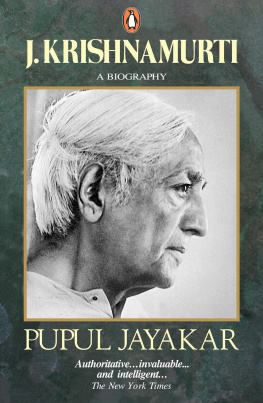

Pupul Jayakar - J. Krishnamurti: A Biography

Here you can read online Pupul Jayakar - J. Krishnamurti: A Biography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Penguin Books Ltd, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:J. Krishnamurti: A Biography

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Books Ltd

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

J. Krishnamurti: A Biography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "J. Krishnamurti: A Biography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

J. Krishnamurti: A Biography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "J. Krishnamurti: A Biography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A Biography

PENGUIN BOOKS

Pupul Jayakar was born in Etawah, Uttar Pradesh, in 1915. She has been closely involved with the development of indigenous culture, handicrafts and textiles in India since the country achieved independence in 1947.

She was president of the Krishnamurti Foundation from 1968 to 1978; she has also served on the boards of several cultural institutions and has written many books on Indian art.

Pupul Jayakar is currently vice president of the Krishnamurti Foundation India, executive vice chairman of the Indian Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, chairman of the Festival of India Advisory Committee, vice president of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, vice chairman of the Indira Gandhi Memorial Trust and an adviser to the Prime Minister of India on heritage and cultural resources.

Pupul Jayakar lives in New Delhi.

To Krishnaji with

profound Pranaams

In the late 1950s Krishnaji, as J. Krishnamurti is known in India and to his friends throughout the world, suggested that I write a book on his life, based on the notes I had kept since I first met him in 1948. I began writing this book in 1978.

I have attempted to write of Krishnamurti the man, the teacher, and his relationships with the many men and women who formed part of the Indian landscape. The book concentrates on Krishnajis life in India between 1947 and 1985, but some recording of his early life became necessary as a backdrop to the unfoldment of the story of the young Krishnamurti. Some new material, hitherto unpublished, has also been included.

The reader will soon notice that Krishnamurti is called by several different names in this book. I have referred to Krishnamurti as Krishna when he was a young person, for so he was known; as Krishnaji from 1947, for by then he was to me the great Teacher and Seer. Ji is a term of respect added to names both of men and women in North India; in an old-fashioned household even the childs name has the suffix added, for it is considered discourteous to address a person by her or his first name. In South India no suffix is added and ji is unknown. It is likely that Annie Besant, because of her close associations with Varanasi, added the ji to Krishnas name as a term of endearment and respect.

Most religious teachers in India have a prefix added to their names, such as Maharshi, Acharya, Swami, or Bhagwan. Krishnaji never accepted any such title. Krishnaji referred to himself in the dialogues or in his diaries either as K or as the impersonal we, to suggest an absence of the I, the egos sense of individuality. In this book, therefore, when I refer to the man or the teacher in an impersonal manner, I refer to him as Krishnamurti or as K.

Krishnaji agreed to hold dialogues with me, and these form part of the book. Most of the writing is from notes kept by me during or immediately after conversations or dialogues. From 1972 onwards, some of the dialogues were on tape and have been taken from there.

Certain incidents discussed in the bookKrishnajis meetings with Indira Gandhi, his relationship with Annie Besantcould have become controversial. These chapters I read aloud to Krishnaji for his comments. I also sent Indira Gandhi the chapter on her meetings with him; she suggested some minor changes, which have been incorporated.

I wish to acknowledge my deep gratitude to Sri Rajiv Gandhi for permission to include the letters of Indira Gandhi; to the Krishnamurti Foundation, England, for permission to publish the dialogues held by me with Krishnaji at Brockwood Park; to the Krishnamurti Foundation, India, for permission to publish the dialogues and talks in India; to Smt. Radha Burnier, President, Theosophical Society, for all her kindness and help in making available material from the archives of the Theosophical Society; to Sri Achyut Patwardhan for his many conversations; to Smt. Sunanda Patwardhan for giving me access to her notes and personal records; to my daughter Radhika and her husband, Hans Herzberger, for their critical comments; to Sri Murli Rao for certain manuscripts he brought to my notice; and to the many other friends who have shared their experiences with me. I would also like to acknowledge Sri Asoke Dutt for his friendship and immense help in making the publication possible; to Mr. Clayton Carlson of Harper & Row for his valuable suggestions, interest, and support; to Sri Benoy Sarkar for his valuable help in sorting out and collating the photographs; to the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad; to the heirs of Mitter Bedi; to Asit Chandmal; Mark Edwards, and A. Hamid, for permission to use their photographs; to A. V. Jose for his overall support and supervision; and to M. Janardhanan for bearing with me in preparing the manuscript.

Tethered Bird

Awake, arise, having approached the great teacher, learn. The road is difficult, the crossing is as the sharp edge of a razor.

KATHA UPANISHAD III

I first met Krishnamurti in January 1948. I was thirty-two years of age and had come to live in Bombay after marrying my husband, Manmohan Jayakar, in 1937. My only child, a daughter, Radhika, was born a year later.

India had been independent for five months and I saw a sweet future stretching ahead. My own entry into politics was imminent. It was a time when men and women involved in the freedom struggle had also turned to what was then known as social or constructive programs initiated by Mahatma Gandhi. This covered every aspect of nation building, particularly those activities related to village India. From 1941 I became very active in organizational matters related to village womens welfare, cooperatives, cottage industries. For me, it was a tough and rigorous initiation. With freedom, the aftermath of partition saw me at the center of the main relief organization set up in Bombay for refugees who were pouring into the country from Pakistan.

One Sunday morning I went to see my mother, who lived in Malabar Hill, Bombay, in an old rambling bungalow roofed with country tiles. I found her with my sister Nandini getting ready to go out. They told me that Sanjeeva Rao, who had studied with my father in Kings College, Cambridge, had come to see my mother. He saw that even after several years of mourning, she was still in great sorrow at my fathers death. He had suggested that she might be helped by meeting Krishnamurti. An image came suddenly to my mind: the mid-1920s, the school at Varanasi where I was a day student. I remembered seeing a very young Krishnamurti, a lean, beautiful figure, seated cross-legged, dressed in white, and I, one of fifty children, laying flowers before him....

I had nothing to do that morning, so I accompanied my mother. When we reached Ratansi Morarjis house on Carmichael Road, where Krishnamurti was staying, I saw Achyut Patwardhan, standing outside the entrance. In recent years he had become a revolutionary and freedom fighter, but I had known him since we were children at Varanasi in the 1920s. We spoke together for a few moments before we went into the sitting room to await Krishnamurti.

Krishnamurti entered the room silently, and my senses exploded; I had a sudden intense perception of immensity and radiance. He filled the room with his presence, and for an instant I was devastated. I could do nothing but gaze at him.

Nandini introduced my tiny, fragile-bodied mother and then turned and introduced me. We sat down. With some hesitation, my mother began to speak of my father, her love for him and of her tremendous loss, which she seemed unable to accept. She asked Krishnamurti whether she would meet my father in the next world. By then the intensity of heightened perception his presence had first evoked had started to fade, and I sat back to hear what I expected to be a comforting reply. I knew that many sorrowful people had visited him, and I assumed that he would know the words with which to comfort them.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «J. Krishnamurti: A Biography»

Look at similar books to J. Krishnamurti: A Biography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book J. Krishnamurti: A Biography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.