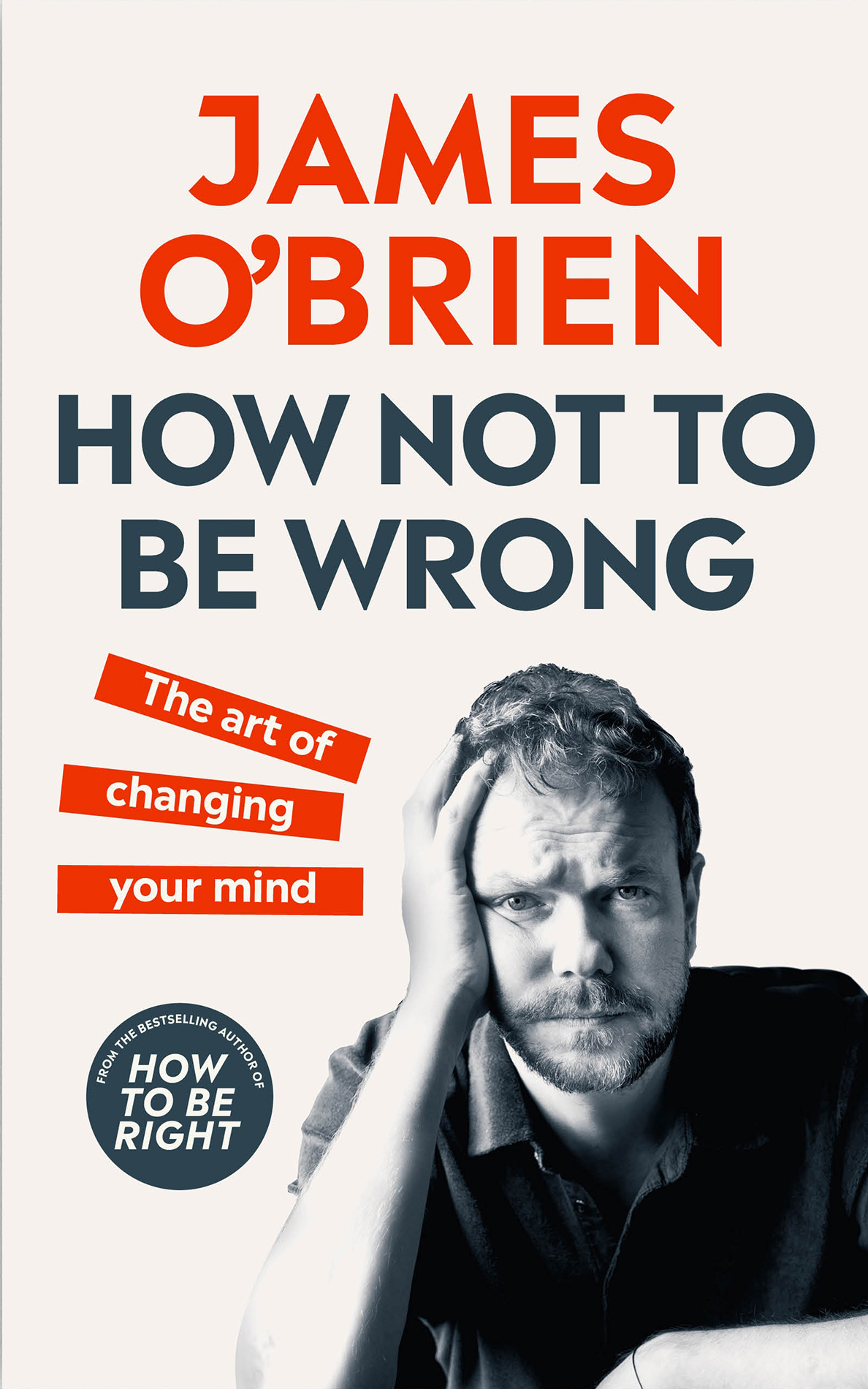

James OBrien

HOW NOT TO BE WRONG

The art of changing your mind

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JAMES OBRIEN IS AN award-winning writer and broadcaster whose journalism has appeared everywhere from the TLS to the Daily Mirror. His daily current affairs programme on LBC has over 1.2 million weekly listeners and his first book, How To Be Right, was a Sunday Times bestseller, which won the Parliamentary Book Award for Best Political Book by a non-politician. He is often to be found on Twitter trying not to get into arguments unless absolutely necessary.

@mrjamesob

For my mum, Joan OBrien, and her granddaughters, Elizabeth and Sophia.

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

W.B. Yeats, The Second Coming

INTRODUCTION

THERE IS NO POINT having a mind if you never change it. We should change our minds when we realise we are wrong. We realise we are wrong or at least that we are not necessarily right after being exposed to superior science or stronger arguments, experiences and evidence that refute our previous position. In short, by listening, thinking and learning. There should be no shame in admitting to being wrong. Instead, we should be applauded for our honesty, humility and emotional intelligence. And there should be no suggestion that admitting to being wrong about something somehow dilutes our overall credibility or reduces the likelihood of us being right about anything else.

It sounds simple and straightforward and yet its far from easy. Pride, fear, vanity, loyalty, even our sense of self can lead us all to various positions from which it feels almost impossible to climb down. We are living in a furiously fast-moving age where our once-reliable fact-checking faculties are buckling under the sheer weight of conflicting and contradictory information. The very concept of objective truth is under siege from forces that, in purely technological terms, didnt exist 20 years ago. Worse, it is a world in which empathy, perhaps second only to evidence as a catalyst for changing our minds about the most important issues, is increasingly denigrated and devalued.

All of this is rendered infinitely worse by what is perhaps best understood as the accelerating footballification of public discourse. This is where we assess an action not by what has actually been done on the metaphorical pitch but instead by the shirt colour of the person who has done it. If theyre on our team we cheer them passionately; if theyre playing for the opposition we furiously boo absolutely identical behaviour. As the Covid-19 pandemic swept the planet in early 2020, it quickly became clear that a widespread inability even to question the integrity of favoured political leaders, never mind the wisdom of remaining blindly hitched to their slogan-covered wagons, could quite literally have lethal consequences.

This is a book about being wrong. In it, I will try to be unflinchingly honest about my own retreats from previous positions, because I cant think of any better way to get right inside this increasingly prevalent problem of blind tribalism. In much of society today, I see open-mindedness derided as weakness, admissions of fallibility held up as evidence of deliberate dishonesty and, most incredibly, the widespread embracing of demonstrably dangerous and dishonest positions purely to upset the other side. As a radio phone-in host blessed with an incredibly diverse and articulate listenership, I have been uniquely positioned to observe the drawing up of battlelines that, without a fairly profound shift in the way we discuss controversial issues, seem destined to remain in place for generations to come. It is a situation that terrifies me and makes me worry for my childrens future. It is perhaps best summarised by an English caller, married to an Indian woman, who explained to me in the middle of 2019 that he knew his political hero was a liar, a racist and a fraud, but that he offered him full-throated support, that he actively enjoyed being lied to, because it upsets people like you. Im still not sure precisely what he means but I hope to be closer to understanding him by the end of this book. It seems pretty clear, though, that some of the responsibility for his outwardly outrageous perspective might lie not just with people like me, but with me personally.

And so this will have to be an intensely personal book and I am genuinely intimidated by this fact. For much of my life, I found it almost impossible to retreat from any position, even if Id only arrived at it five minutes previously. I was the insufferable dinner party guest who refused to let things lie, the bloke in the pub who could never agree to disagree. Looking back, it was as if I felt that being wrong would expose a vulnerability I was determined never even to contemplate, as if the foundations of my life and personality would somehow be shaken by acknowledging even to myself that I could be in the wrong. When I began to understand this and to search for its roots, I came to realise that I had lived much of my life in a highly adrenalised state an almost permanent fight or flight condition and until very recently I would have been rather proud of that. These, I would have argued, are the tools that I need to be me and these reactions and reflexes are part of who I am. The crashing lows are the price you pay for the dizzying highs. Show absolute self-confidence to the world and the world will bend to your will; crush your enemies before they mobilise and they will never be able to hurt you again. Everything is a battle and only the strongest will prevail.

It has been sobering, to say the least, to come to understand that none of it was necessary, that many of the personal attributes I took to be strengths were in fact serious and potentially very dangerous weaknesses. Now that I am able to recognise where I was going wrong, I see people with very similar mindsets and backgrounds continuing to flourish in public life and I cant help but wonder whether this weaponised resilience has contributed to the current chaos and confusion on both sides of the Atlantic.

I still get the old feelings when I fall into pointless rows on Twitter (are there any other kind?). Theres a bolus of tension in my gut that attributes ludicrous importance to winning. The frustration felt when your rival wont admit your point, or concede defeat, brings you back for more and more until the original argument has been so clouded with confusion, claim and counterclaim that you struggle to remember what actually started it. Ten minutes later, you feel utterly ridiculous and often a bit shaky, but in the moment it felt as if nothing else mattered. In reality, of course, it really didnt matter at all. Not one jot. You will probably know someone the same; you may well be suffering similarly yourself.

As a schoolboy debater, I positively relished arguing from positions I disagreed with because it seemed a much sterner test of rhetorical skill than arguing from the head or the heart. But at some point in the intervening years, I realise now, I had begun to consider being right as less important than being seen to win. This pursuit of victory of administering the knockout blow came to completely overshadow the importance of examining my own views and understanding. I stopped, to stretch the metaphor, kicking the tyres of my own opinions because I was too busy turbo-charging the engine and congratulating myself on the latest high-speed turn around the circuit of public pontificating and arguing. Of course, the situation was hardly helped by the fact that I was building the career I thought Id always wanted on the back of this dubious but very particular set of skills. So in this book I am not seeking to persuade you that my various positions and opinions are somehow right and everyone elses wrong, but rather to show how much better it would be if none of us were unthinkingly wedded to any of them.

Next page