John Kaag

SICK SOULS, HEALTHY MINDS

John Kaag is the author of American Philosophy: A Love Story, which was named a New York Times Editors Choice and an NPR Best Book of the year, and Hiking with Nietzsche: On Becoming Who You Are, which was also an NPR Best Book of the year. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, Harpers Magazine, and many other publications. He is professor of philosophy at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, and lives in Carlisle, Massachusetts. Twitter @JohnKaag

Sick Souls, Healthy Minds

Sick Souls, Healthy Minds

How William James Can Save Your Life

John Kaag

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2020 by John Kaag

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

First paperback printing, 2021

Paperback ISBN 9780691216713

Cloth ISBN 9780691192161

ISBN (e-book) 9780691200934

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Rob Tempio and Matt Rohal

Production Editorial: Natalie Baan

Text Design: Leslie Flis

Cover Design: Jason Anscomb

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Katie Lewis and Maria Whelan

Copyeditor: Hank Southgate

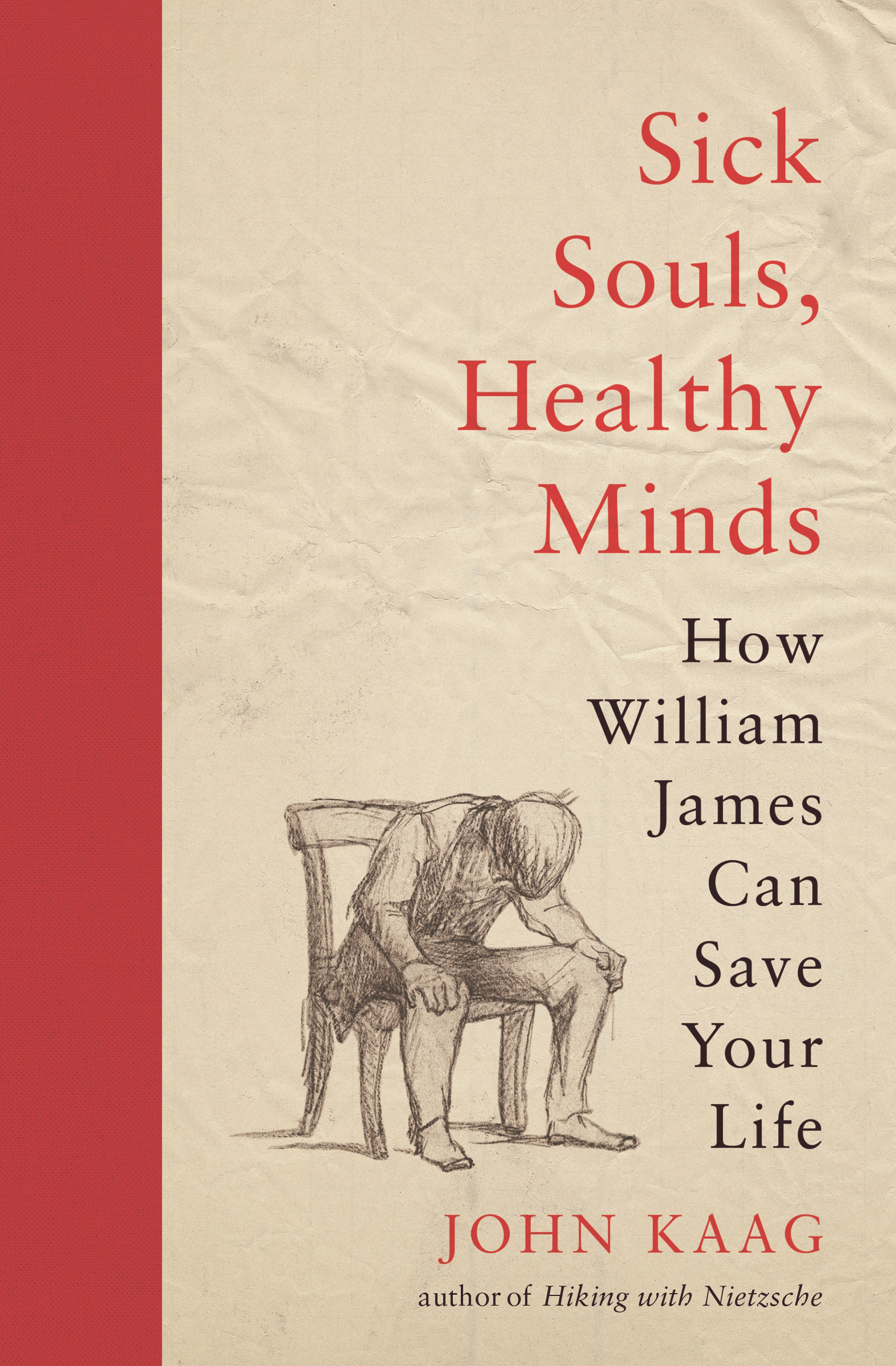

Cover Credit: William James, Here I and Sorrow Sit, red-crayon drawing. MS Am 1092.2 (54), Houghton Library, Harvard University

Versions of these chapters have been excerpted in slightly altered form in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Aeon Magazine, and The Towner Magazine.

Printed in the United States of America

For Doug Anderson and for Kathy

Contents

Sick Souls, Healthy Minds

Prologue

A DISGUST FOR LIFE

Take the happiest man, the one most envied by the world, and in nine cases out of ten his inmost consciousness is one of failure.

William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, 1902

I AM A LOW-LIVED WRETCH. Ive been prey to such disgust for life during the past three months as to make letter writing almost an impossibility. William James was on the brink of adulthood and, as he confessed to his friend Henry Bowditch in 1869, on the brink of collapse. In the coming two decades, James would writeletters, essays, booksincessantly, like his life depended on it. Hed become the father of American philosophy and psychology, but when he wrote to Bowditch he couldnt foresee any of it. Actually, he often struggled to see the next day.

James had just returned to his fathers house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, after an eighteen-month sojourn in Berlin. This trip, a quest in search of good health and sanity, had failed. More accurately, it had proven deeply counterproductive. He was, if anything, deeper in the pit. Back in New England, the prospect of earning his medical degreewhich hed go on to do without difficultygave him little joy. His heart wasnt in it, wasnt in anything. In truth, it may have been in too many things at once.

Jamess polymathic abilities were, partially, responsible for his divided selfpart poet, part biologist, part artist, part mystic. He was pulled in too many directions, like a man on the rack, and therefore, for a time, couldnt move, forward or otherwise. He was a man of disparate pieces, and in his early years he nearly failed to hold himself together. But there was something else. James was also philosophically stuck, mired in thoughts that had plagued countless thinkers before him: maybe human beings are determined by forces beyond their control; maybe their lives are destined from the start, fated to end tragically and meaninglessly; maybe human beings, despite their best efforts, cant act on their own behalf, as free and vibrant beings; maybe theyre nothing but cogs in an unfortunately constructed machine.

Meaninglessness was the problem, Jamess problem, and it drove him to the edge of suicide. In the late 1860s, he used a red crayon to sketch a portrait in a notebook: a young man sitting alone, shoulders hunched, head down. Over the figure James wrote, HERE I AND SORROW SIT. But if you look closely, very closely, you will see a faint line that makes all the difference. Read it again: the N might actually be an M. It says, HERE I AM. This was a self-portrait.

In his later life, James described an individual, all too common to the neighborhood around Harvard, who is, from birth, psychologically vexed: There are persons whose existence is little more than a series of zigzags, as now one tendency and now another gets the upper hand. Their spirit wars with their flesh, they wish for incompatibles, wayward impulses interrupt their most deliberate plans, and their lives are one long drama of repentance and of effort to repair misdemeanors and mistakes. These are, in Jamess words, the sick-souled, those who were just as likely to graduate from the Ivy League as to commit suicide at McLean Asylum, a stones throw from Harvard Yard. Rumors have swirled for more than a century that James had his own stint at the hospital, but they have faded in the hundred years after his death. Today, James is usually described as a man who faced mental illness without the help of doctors.

This isnt exactly true: he was the doctor. William Jamess entire philosophy, from beginning to end, was geared to save a life, his life. Philosophy was never a detached intellectual exercise or a matter of wordplay. It wasnt a game, or if it was, it was the worlds most serious. It was about being thoughtful and living vibrantly. I would like to offer the reader Jamess existential life preserver. Of course, in the end, life is a terminal condition. No one makes it out alive. But some authorsJames most notablycan help us survive, so to speak, by preserving and passing on what is most important about being human before we pass away. James crafted what he called a philosophy of healthy-mindedness. It may not be a formal antidote for the sick soul, but I like to think of it as an effective home remedy.

Such a philosophy would be wholly unnecessary were it not for the fact that so many of us seem to teeter on the brink of the abyss. In 2010, I was there myself. I was thirty, in the midst of a divorce, and had just watched my estranged, alcoholic father die. And I was at Harvard on a postdoc writing aboutyou guessed itWilliam James. I was supposed to be finishing a monograph about his notion of creativity, an uplifting book about the salvific effects of his philosophy known as pragmatism. Pragmatism, James informed his readers in 1900, holds that truth should be judged on its practical consequences, on the way that it impacts life. Its a nice thought, except when life itself seems pretty meaningless. James knew this and crafted a philosophy to address this painful insight. It took me several miserable years to grasp it.

I think William Jamess philosophy saved my life. Or, more accurately, it encouraged me not to be afraid of life. This is not to say it will work for everyone. Hell, its not even to say that it will work for me tomorrow. Or that it works all the time. But it did happen, at least once, and that is enough to make me eternally grateful and more than a little hopeful about the prospects of this book. James wrote for our age: one that eschews tradition and superstition but desperately craves existential meaning; one that is defined by affluence but also depression and acute anxiety; one that valorizes icons who ultimately decide that the life of fame is one that really ought to be cut short prematurely. To such a culture, James gently, persistently urges, Be not afraid of life. Believe that life is worth living, and your belief will help create the fact. On good days, when my own sick soul speaks only quietly, Jamess insistence works very well. On bad days, it helps me hang on. As Ive come to admire and cherish Jamess philosophy as a lifesaver, Ive also encountered a growing number of friends, neighbors, students, and strangers who flounder in the profoundest ways possible.