FLOWERS OF TIME

Flowers of Time

ON POSTAPOCALYPTIC FICTION

MARK PAYNE

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2020 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Payne, Mark, 1967 author.

Title: Flowers of time : on post-apocalyptic fiction / Mark Payne.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2020] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020002321 (print) | LCCN 2020002322 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691205427 (hardback ; acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780691205946 (paperback ; acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780691206400 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Apocalypse in literature. | Apocalyptic fictionHistory and criticism. | End of the world in literature. | DystopiasHistory.

Classification: LCC PN56.A69 P39 2020 (print) | LCC PN56.A69 (ebook) | DDC 809.3/9372dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020002321

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020002322

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Anne Savarese and Jenny Tan

Production Editorial: Ellen Foos

Jacket/Cover Design: Layla Mac Rory

Production: Brigid Ackerman

Publicity: Alyssa Sanford and Amy Stewart

Copyeditor: Daniel Simon

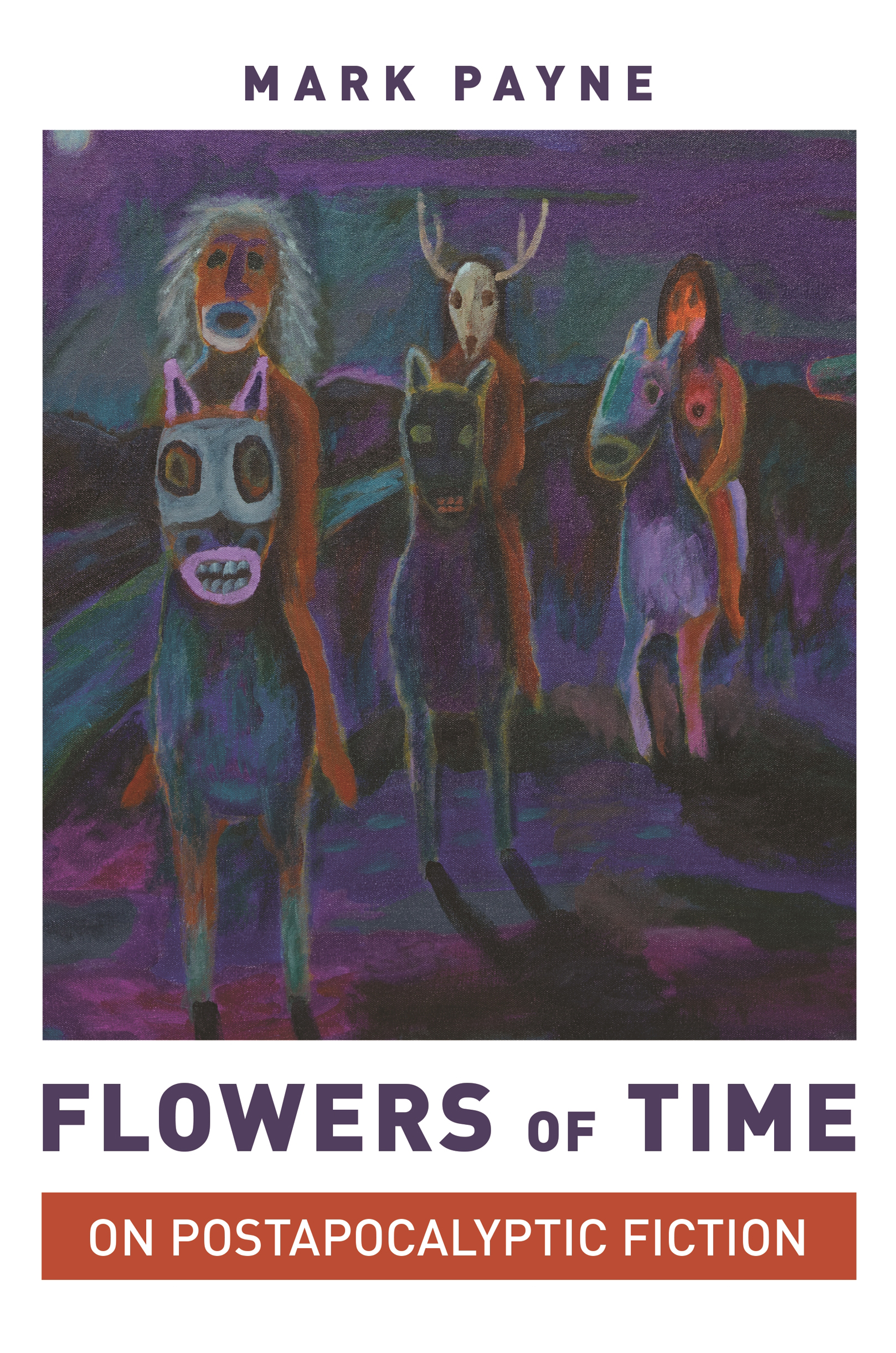

Jacket art: Jim Denomie, Spiritual Landscape, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Bockley Gallery

The very flower of Time, which never bloomed before, and never by any possibility can bloom again.

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE, ENGLISH NOTEBOOKS , JULY 26TH [1857], SUNDAY, OLD TRAFFORD

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I AM GRATEFUL to many friends for their intellectual companionship while working on this book. At the University of Chicago, Deme Kasimis of the Department of Political Science offered invaluable recommendations on Rousseau and marronage. Cody Jones of the Department of Comparative Literature was an ever-present interlocutor on theory, fiction, and everything in between. I am also grateful to Andrei Pop of the Committee on Social Thought for sharing with me his boundless knowledge of the wide world of speculative fiction.

Conversations on Native American history with Jonathan Lear, and with Scott and Urban Bear Dont Walk, continue to resonate in this book. Urban has now passed on, but I will always be grateful to him for sharing his thoughts with me on the walks, drives, and hospital visits we took when I was visiting Crow country.

Sam Cooper of Bard High School in Queens helped me see connections between classical literature and modern speculative fiction that I would not have seen without him, and I learned a lot from his own work in these areas. Brooke Holmes of Princeton University encouraged me to think harder about what I was doing, as she always does. In England, Tom Phillips of the University of Manchester, David Fearn and Victoria Rimell of the University of Warwick, and Miriam Leonard of University College London lent receptive ears to the lines of kinship I was trying to establish.

Audiences at UCLA, Florida State University, the University of Manchester, the Boghossian Foundation, Johns Hopkins University, and the Franke Institute for the Humanities at the University of Chicago helped me move forward with their lively discussions of papers I presented at various stages of this project.

This book was conceived, and a first draft written, during a yearlong leave from the Division of Humanities at the University of Chicago. I am thankful to Deans Martha Roth and Anne Robertson for the support that made it possible.

Many thanks too to Anne Savarese at Princeton University Press for taking the manuscript on and for recruiting the two excellent readers whose insights and suggestions made it a much better book than it would otherwise have been.

An earlier version of part of was published as Post-apocalyptic Humanism in Hesiod, Mary Shelley, and Olaf Stapledon in Classical Receptions 12, no. 1 (2020): 91108. My thanks to the editors and readers of the journal for their enthusiasm.

Last but very much not least, thanks to my wife and children for putting up with some difficult times during my work on this project. One of the claims I make in the book is that postapocalyptic fiction is a cheerful genre, but I dont know that any of you would have guessed that while I was working on it. Thanks to Laura, Carolyn, and Alice for all your love and support.

FLOWERS OF TIME

INTRODUCTION

Postapocalyptic Pastoral

THE APOCALYPSE is everywhere right now. In beach reads and blue chip fiction; in comic books and young adult novels; in streaming TV shows, major motion pictures, and ironic art-house cinema. Wherever you look, small groups of beleaguered survivors are banding together to outsmart zombies or crazed survivalists, and generally doing their best to get by on a planet ravaged by pollution, consumerism, and reckless resource extraction.

Critics have begun to roll their eyes in the face of this abundance. In Whats the matter with dystopia? Ursula Heise echoes biologist Peter Kareiva in questioning the value of the current outpouring of apocalyptic imaginings. What does such apocaholism accomplish, other than encouraging us to turn our backs on the difficult work of fighting global inequity and ecological destruction, so that we can fantasize instead about the hipster DIY and maker culture that might come after the end of days?

For all its present ubiquity, apocalyptic fiction is an ancient form of the human imagination. It includes the biblical story of Noah, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and the Works and Days of the ancient Greek poet Hesiod as well as a vast array of modern examples. A basic distinction can be made in this archive between apocalyptic fictions, which focus on the end of days itself, and postapocalyptic fictions, which imagine the life that human beings might lead after the apocalyptic event has passed. In this book, I focus on the latter: large-scale works of literary fiction that stage how new forms of life emerge from catastrophe, how survivors adapt to the altered conditions of existence, and the various ways in which the past asserts its claims on themboth the immediate past of the world that is lost as well as the deep past of prehistory and the anthropological imagination that returns with this loss.

Postapocalyptic fiction is political theory in fictional form. Instead of producing arguments in favor of a particular form of life, it shows what it would be like to live that life. This is its mode of persuasion. Modern postapocalyptic fiction begins with Mary Shelleys The Last Man (1826), which stages the return of small-scale agrarianism in the aftermath of catastrophe, but this aspect of postapocalyptic fiction is not local to modernity. Shelley presents the agricultural survivalism of the ancient Greek poet Hesiod (eighth century BCE) as the model for the postapocalyptic social thought of her novel, and for ancient philosophers, Hesiods poetry was a regular starting point for thinking about the foundations of social order and cohesion.

Hesiod was the first Greek thinker to offer a decisive, first-person articulation of the ideas of justice, obligation, and human relationality that went by the name of