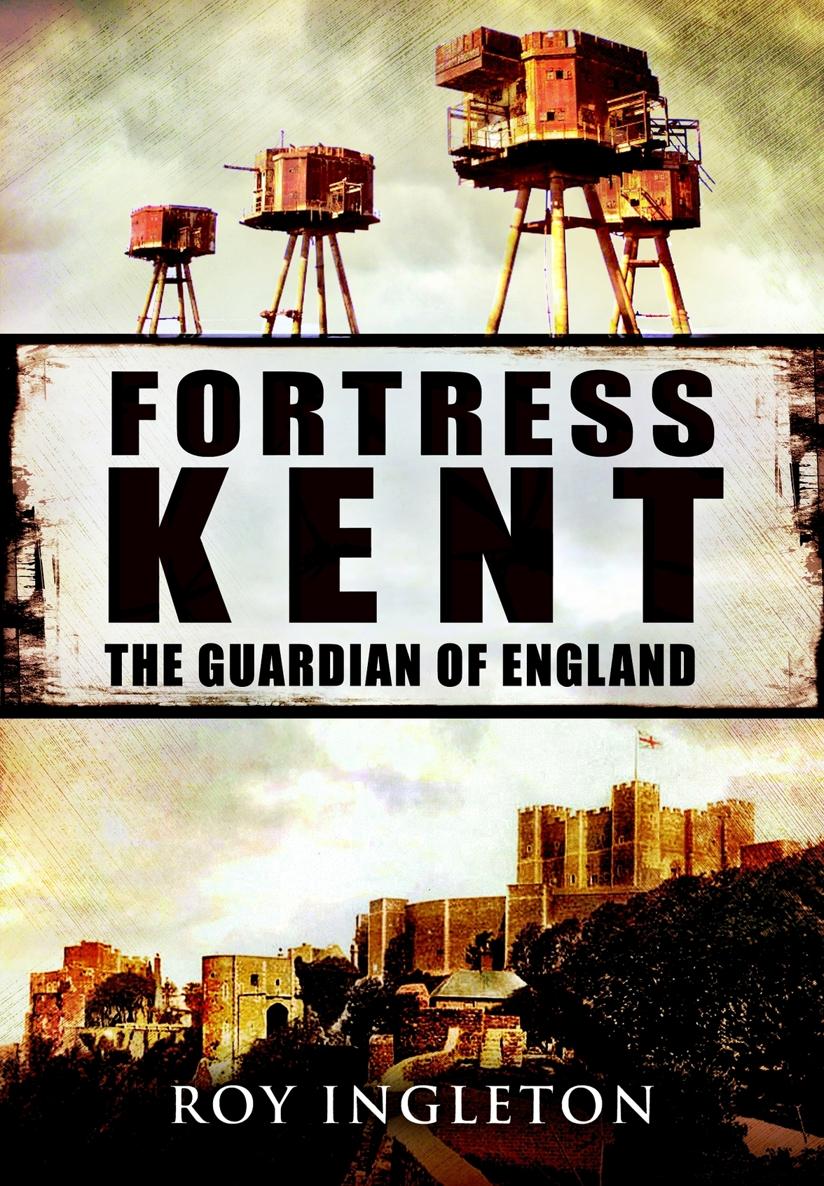

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Roy Ingleton 2012

9781783036066

The right of Roy Ingleton to be identified as the Author of this Work has been

asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the

Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire.

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen &

Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword

Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe

Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The

Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Since the dawn of civilisation, Britain has been menaced by foreign powers and invading hordes, anxious either to pillage and plunder or to invade and rule over this green and pleasant land.

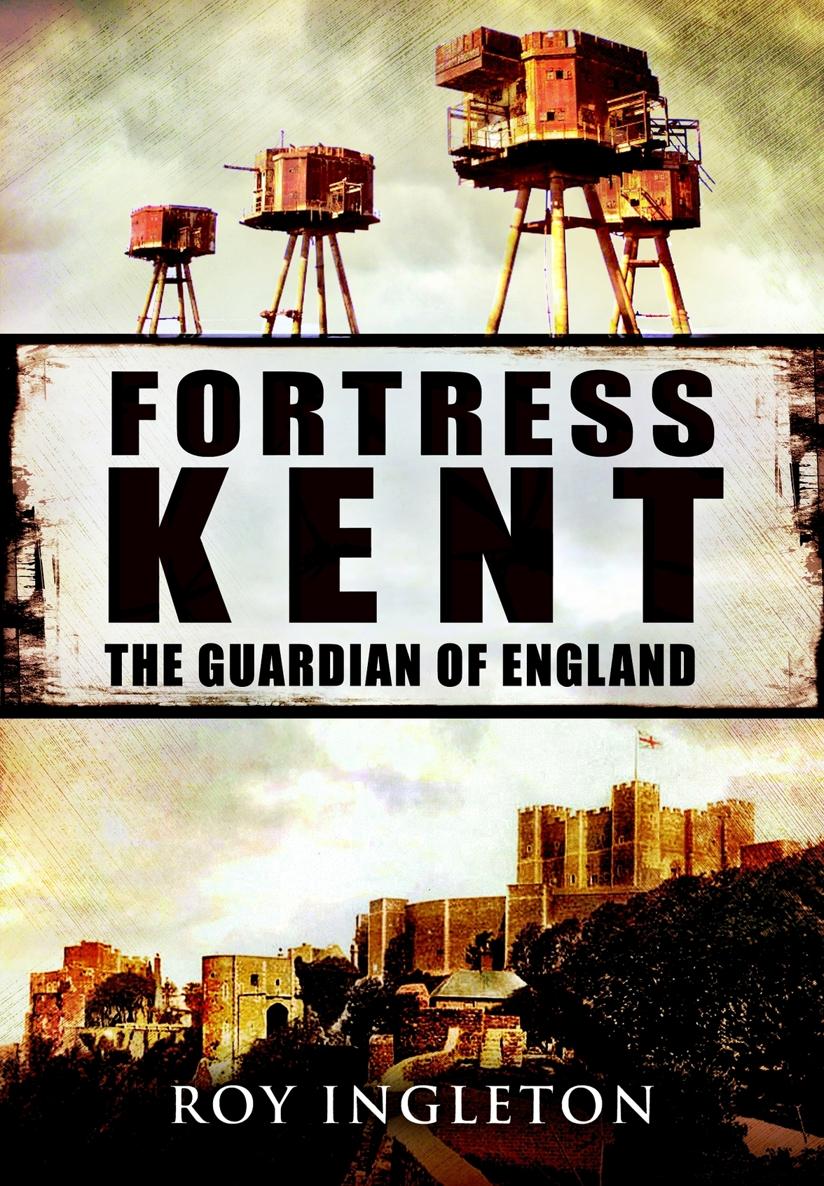

Situated on the extreme south-eastern corner of England, the county of Kent is the nearest point to continental Europe, and has so been the preferred landing point for most of these incursions. From the time of the Romans and the Angles, Jutes and Saxons to the Second World War, the Men of Kent and Kentish Men have had to erect and maintain defensive structures, from Iron Age forts to 1940 pillboxes, from the Royal Military Canal to the anti-tank ditches carved out of the hills around the Kent coast during the Second World War, culminating in the construction of deep shelters in anticipation of a nuclear attack.

This book is the story of these measures: the threats that led to the erection and construction of various defensive obstacles, their up-keep and garrisoning, and, in some cases, their ultimate destruction. It is laid out in more or less chronological order, with chapters devoted to the main periods of construction, although there is some overlap and the dates may not always fit comfortably within such periods.

Many of the illustrations are the authors own, and as far as the remainder are concerned, where copyright is known or believed to exist, acknowledgement has been made or permission sought. To the best of my knowledge and belief, any others are in the public domain, but I apologize if there has been any unintentional oversight and will undertake to correct this in any future editions.

Roy Ingleton

Maidstone, 2011

Chapter 1

The earliest constructions: Iron Age (first century BC)

Prior to the last days of the so-called Iron Age, that is to say the last century before Christ, there is little known of any significant fortifications in Kent: indeed, the sparse population of Kent, and the lack of foreign would-be invaders willing to face the perils of the English Channel or the North Sea in any numbers during those early days, probably did little to convince the population of any such need.

Around 500 BC, a number of immigrants arrived from Gaul and Flanders, but their landings were generally unopposed; after all, with a population of under a million scattered over the entire country, there was plenty of room for everyone. These newcomers to Kent (Cent in Old English, Cantia regnum in Latin) joined the existing settlers in constructing wattle-and-daub huts to live in, engaged in arable and livestock farming and gave little thought to defending themselves from hostile invasions from overseas. They were, perhaps, more concerned about their near neighbours for, although it has long been thought that this period was a peaceful and settled one, recent discoveries have prompted a rethink. In 2011, archaeologists exploring a hill fort at Fin Cop in Derbyshire discovered the remains of a large number of women, children and babies who appear to have been massacred by a rival tribe around 400 BC. Slavery having been an increasingly important export during the Iron Age, the menfolk were probably carted off to serve as slaves or warriors by the victorious tribe before the less valuable women and children were stripped of their meagre belongings and stabbed or strangled before being tossed unceremoniously into the forts defensive ditch, where a 13-foot limestone wall was toppled onto the pitiful cadavers.

Although no similar evidence of such violence has been found in Kent, it is probable that such forts as were constructed here during the latter part of the Iron Age were used more as a refuge against other local tribes than from foreign invaders. However, by 100 BC things had changed considerably and the seemingly irresistible expansion of the Roman Empire was forcing many of the existing peoples of Europe the Franks, Visigoths, Lombards and other barbaric tribes to seek land outside the influence of Rome, and no doubt many cast covetous eyes on that green and pleasant land just across a narrow strait of sea. The Celtic people of Kent were not unaware of this. They had for some years been trading with merchants from as far away as the Middle East and gained their news of the outside world from this source.

Among the first to arrive in Kent in any numbers were the Belgae who crossed over to East Kent from the Low Countries during the early part of the first century BC. Their gradual but inexorable migration westwards prompted the existing population to set up a number of hilltop camps, the remains of just a few of which still exist. As the name implies, these defences were usually built on a hilltop that provided a good view and represented a significant obstacle to invaders. The site was generally levelled with one or more rows of ditches dug into the hillside to further impede assailants, the excavated earth being piled up to form an earthen rampart, often reinforced by a timber palisade or stone wall. Although often seen as simple, unsophisticated defensive structures, many Iron Age earthworks incorporated ingeniously arranged diversions in which the attacker could be trapped and eliminated. This represented a military sophistication not seen again in this country until around the fourteenth century.

On the southeast coast, the great white cliffs that Shakespeare described as the... high, upreared and abutting fronts [that] the perilous ocean parts asunder (Henry V) extend for 13 miles, and the only gap in these towering obstacles occurs at Dover,where the shallow River Dour debouches into the sea. This, coupled with its close proximity to France, has placed Dover at risk and needing to be defended since the earliest days in the countys history. In 1992, a Bronze Age boat dating from 1300 BC was discovered beneath Townwall Street, clearly demonstrating that Dover has been a significant maritime centre for more than three millennia.