For Kristen, whose siren song enchants me more every day

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2020

Copyright Vaughn Scribner 2020

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789143133

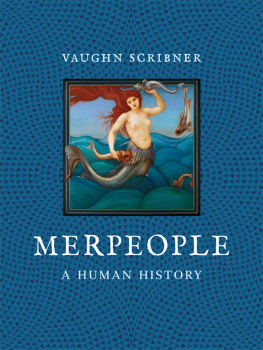

Introduction

M erpeople are everywhere. A mermaid is the mascot for the most popular and profitable chain of coffee shops in the world, films and television shows featuring merpeople abound and a child or indeed an adult, if they so wish can partake in mermaid lessons through Mermaid University programmes in North America. But humanitys obsession with merpeople is hardly new. No matter where or when humans have lived, they always seem to find mermaids and mermen. It is in this universal pattern that Merpeople: A Human History finds its core, as it uses merpeople to gain a deeper understanding of one of the most mysterious, capricious and dangerous creatures on Earth: humans.

Although representations of merpeople transcend temporal and geographical constraints, this book analyses how, from roughly 1000 BCE to the present, Westerners changing perceptions of mermaids and mermen (also called tritons) reveal deeper understandings of myth, religion, science, wonder and capitalism. Whether gracing an English cathedral wall or an American cinema screen, images of merpeople have always enchanted Western audiences. But these creatures relevance exceeds stone or screen physical imagery, in fact, accounts for only a portion of merpeoples importance in understanding humanitys fascination with these strange hybrids. Like those flawed creatures who created them, mermaids and tritons are multifaceted, volatile entities wedded to a variety of equally volatile ideologies.

Of course, merpeople were hardly the only hybrid creatures that Westerners chased to the ends of the Earth. Mythical hybrids such as the unicorn, sphinx, centaur, griffin and satyr (to name only a few) long enthralled medieval, Renaissance and early modern thinkers, while late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century scientists grappled with oddities like the opossum, platypus and kangaroo. For philosophers and religious leaders, these hybrid creatures represented danger as much as hope, wonder as much as horror. They were unnatural manifestations of a realm that humans did not fully understand, and thus might lead mankind into a strange, disorderly world of confusion and destruction. Yet they also, importantly, might help humanity to better understand its place in the world of wonders that seems to reveal more of itself with every day.

Monster theory and hybrid studies are imperative for Merpeople: A Human History, especially in their ability to reveal the humanity in such seemingly foreign, incongruous manifestations of the natural world. The historian Erica Fudge recently posited that reading about animals is always reading through humans... paradoxically, humans need animals in order to be human. Harriet Ritvo preceded Fudges assertions, arguing that the classification of animals... is apt to tell as much about the classifiers as it is about the classified.conceptions of classification, and even humans supposed supremacy on the planet? These were not questions to be taken lightly.

Merpeoples hybridity has helped them maintain a presence in both scientific and mythological camps. In many peoples minds, mermaids and mermen remain mythical creatures more suitable for bedtime stories than scientific tracts. Yet for others merpeople symbolize the outer limits of our scientific and mythological investigations. Just as the evolution of science has not done away with lingering notions of wonder and myth, so too has our innate need to push boundaries of knowledge led humanity into strange often mind-blowing frontiers of research and self-reflection. Humanitys interaction with merpeople demonstrates our ongoing need for discovery as much as our attempts at regulation and classification. Like the hybrid monstrosities with which humankind has always grappled, humanity maintains a tenuous balance between wonder and order, civilization and savagery.

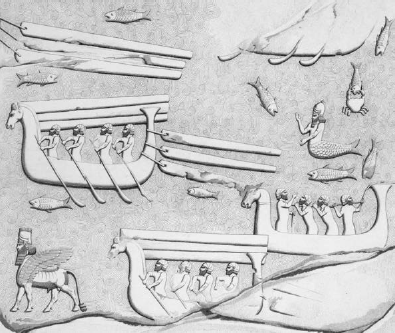

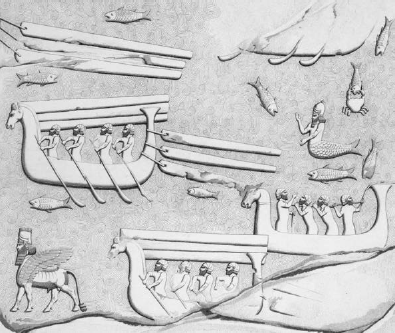

2 Oannes Blessing the Fleet, from an 8th century BCE sculpture uncovered in the ruins of the palace of Sargon II at Khorsabad by Paul-mile Botta. Reproduced in Paul-mile Botta, Monument de Ninive (Paris, 1849).

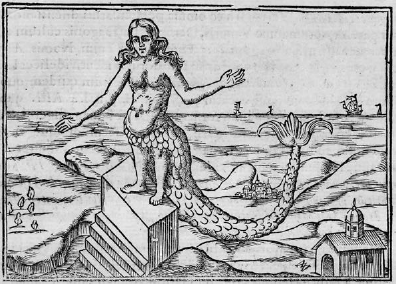

3 Derceto [or Atargatis] Dominating the Sea, from Athanasius Kircher, Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652).

Perhaps nowhere is this fragile equilibrium more obvious than in the early Christian Churchs myriad representations of mermaids and tritons. As will be explored further in

A spate of pagan representations of merpeople followed Oannes and Atargatis, ranging from Greek and Roman depictions of Aphrodite and Venus, respectively, to Pliny the Elders descriptions of mysterious human-fish sea creatures in 80 CE, to the Greeks incorporation of Triton (the origin for the merman) and his wife Amphitrite, to Odysseus fateful encounter with the harpies

Beginning in the third to fifth centuries CE, Church leaders simultaneously adopted, transformed and harnessed ancient pagan symbols of merpeople to assert notions of piety, faith and self-control. Although mermen had long been associated with rape and violence, the early Christian Church was on a mission to dethrone femininity, and had little use for these male monstrosities. Rather, churchmen hoped to transform notions of the Homerian harpy to fit their own means, and in doing so adopted more sexual connotations and imagery in their representations of mermaids.

Physical representations of merpeople were critical to this process. Our modern conception of the mermaid stems directly from early churchmens depictions of these mysterious creatures. Traditionally shown as human females above the waist, with long, flowing hair and bare breasts, a mirror in one hand and a comb in the other (

4 A classical siren clutching a mirror in one hand and a comb in the other has gazed down upon worshippers from the fan-vaulted roof of Sherborne Abbey, Dorset, since 1490.

By the medieval period (the fifth to fifteenth centuries CE), churchgoers throughout Europe worshipped in spaces decorated with overtly sexualized mermaid imagery. Church leaders, meanwhile, cultivated an intimate knowledge of these strange creatures through myriad texts, art and sculpture. Such ubiquity helped to facilitate general acceptance of, and belief in, mermaids.

![Vaughn Jen - Bridges and tunnels : investigate feats of engineering [with 25 projects]](/uploads/posts/book/143664/thumbs/vaughn-jen-bridges-and-tunnels-investigate.jpg)