Windgather Press is an imprint of Oxbow Books

Published in the United Kingdom in 2020 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106-108 Cowley Road, Oxford, OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Windgather Press and the author 2020

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-91118-868-1

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-91118-869-8 (epub)

Kindle Edition: ISBN 978-1-91118-870-4 (mobi)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Windgather titles, please contact:

| United Kingdom | United States of America |

| OXBOW BOOKS | OXBOW BOOKS |

| Telephone (01865) 241249 | Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146 |

| Email: | Email: |

| www.oxbowbooks.com | www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate group

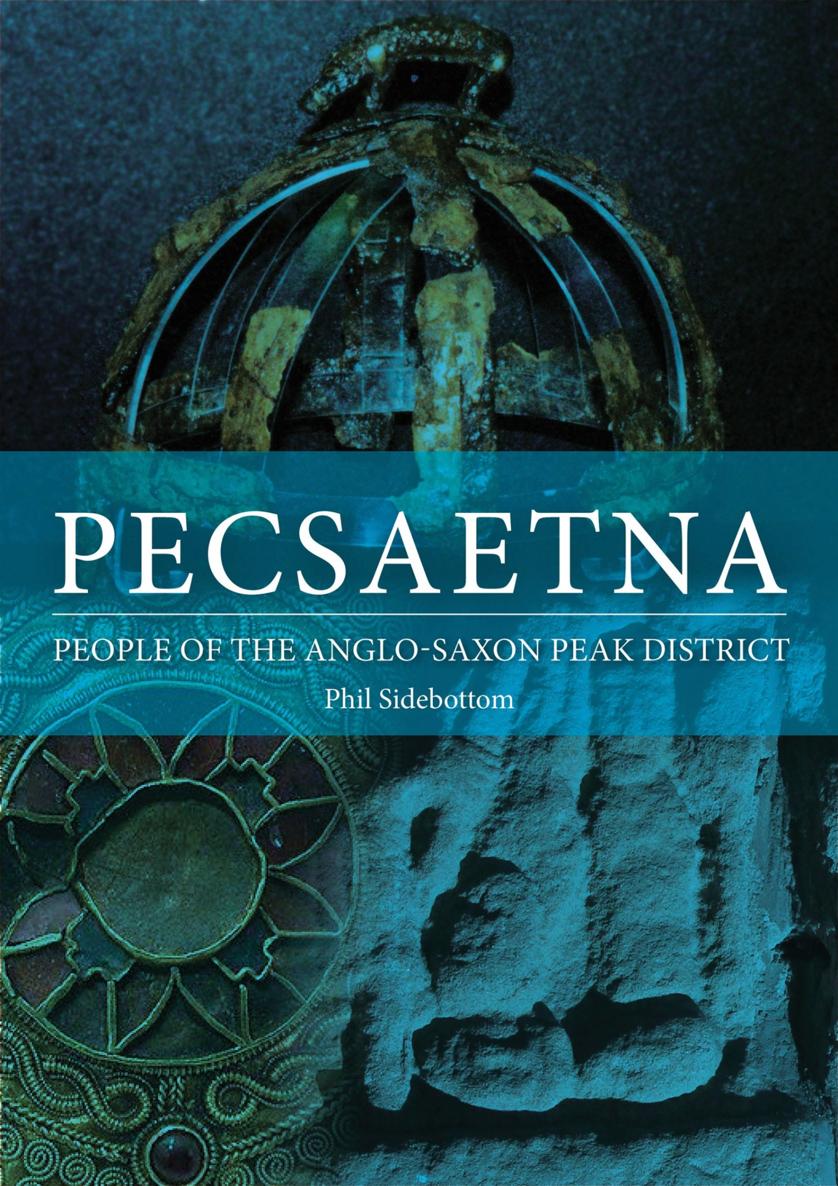

Cover design: Reproduction of the Anglo-Saxon gold and garnet disc from White Low, by permission of Museums Sheffield; other photos by the author.

To my wife Adele for all her encouragement and to the descendants of the Pecsaetna, who are still amongst us

List of Figures

Fig. 1. The location of the Peak

Fig. 2. Simplified geological map of the Peak area

Fig. 3. The principal rivers of Derbyshire and the limestone Peak

Fig. 4. Roman roads in the region

Fig. 5. The Ballidon estate with abandoned Roman farms

Fig. 6. The Tribal Hidage list

Fig. 7. The location of some principal saetna names

Fig. 8. Tribal Hidage territorial reconstruction map

Fig. 9. Extent of the Hamenstan or Peak estates before the Norman Conquest

Fig. 10. The dry limestone valley passing through the village of Whitwell; a possibility for the Whitwell Gap referred to in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles

Fig. 11. Dore and Whitwell with land units reconstructed from the Tribal Hidage in the Peak region

Fig. 12. The location of grange sites mentioned in the text

Fig. 13. Peak place-names

Fig. 14. Scandinavian place-names in Derbyshire and northern Staffordshire

Fig. 15. Fragment of a cross shaft in the south porch at Bakewell church

Fig. 16. 7th-century Anglo-Saxon burials

Fig. 17. The distribution of Anglo-Saxon barrow burials in the White Peak, earthworks and principal sites

Fig. 18. A barrow at Wigber Low excavated in 1987

Fig. 19. The Wigber Low barrow burial, showing the remains of its female interment

Fig. 20. Potentially Christian artefacts found at the Benty Grange Anglo-Saxon burial

Fig. 21. The White Low cross and Merovingian orb from Wigber Low

Fig. 22. The Grey Ditch, Bradwell, in relation to the Roman road, Batham Gate and Brough Lane

Fig. 23. Linear and other earthworks in the northern limestone Peak District and beyond

Fig. 24. Based on Ordnance Survey of 1879: Calver Cross Dyke can be seen to have been compromised by old lead workings at its northern end

Fig. 25. Calver Cross Dyke as it is today

Fig. 26. The boundary of the Ballidon estate in 963

Fig. 27. Primary group monuments in the north Midlands and southern Yorkshire

Fig. 28. Distribution of Secondary monuments around the limestone Peak

Fig. 29. Distribution of Primary monuments around the limestone Peak

Fig. 30. The sarcophagus cover, known as the Wirksworth Slab; Peak group heavy vinescroll at Wirksworth; an example of a Trent Valley group warrior figure at Norbury

Fig. 31. The Peak group of monuments

Fig. 32. Detail of the Hope cross shaft

Fig. 33. The Hope Motte

Fig. 34. South wall of the nave at St Peters, Alstonefield, showing the reused sandstone in the wall fabric

Fig. 35. Portions of possible Roman milestones in Alstonefield church and a fragment of an unfinished cross shaft also at Alstonefield

Fig. 36. The remains of Navio Roman fort at Brough-on-Noe

Fig. 37. The western rampart to Carl Wark fortified outcrop

Fig. 38. The Dore stone, Dore village

Fig. 39. The location of Dore with the Tribal Hidage reconstruction

Fig. 40. The route of the postulated Roman road over Burbage and Houndkirk Moors

Fig. 41. Looking north-east from the Roman road across Dore Moor

Fig. 42. Roman-period walls at Roystone Grange

Fig. 43. Taddington in 1898

Fig. 44. Wirksworth town centre in 1899

Fig. 45. Eyam in 1898

Fig. 46. Bradbourne, showing the church and hall as they were in 1880

Fig. 47. Alstonefield village and church in 1880

Fig. 48. Political saint dedications around the Peak

Fig. 49. The Odin Mine at Castleton

Fig. 50. The traditional lead working areas of the limestone Peak: mines are shown as dots

Fig. 51. A Bakewell cross fragment compared with a shaft from Hexham

Fig. 52. Figures in Roman dress on the shaft in Bradbourne churchyard

Fig. 53. The top of the large Bakewell cross-shaft and a Roman tombstone at Hexham, Hadrians Wall

Fig. 54. The Aethelflaedian and Edwardian forts in north-western Mercia

Fig. 55. The postulated land unit of the Pecsaetna after the loss of the Staffordshire portion of the White Peak

Introduction

This book is intended to pull together our current knowledge of the lost group of people called the Pecsaetna (literally, meaning the Peak Sitters) by synthesising historical and archaeological research towards a better understanding of their activities, territory and identity. This is not an easy task, for this group of people is shrouded in the mists of the so-called Dark Ages and are only known to us by the chance survival of less than a handful of documents. Many years ago, a paper written by Audrey Ozanne (Ozanne 1962/3), focused on the archaeology of this group, in particular, the grave-goods exhumed by the antiquarians Thomas Bateman and Samuel Carrington during the mid-19th century. Ozannes main concern was to try to establish dating horizons for artefacts found in mound burials in the Peak region, concluding that many or most were datable to the 7th century, around a time when Christianity was, historically, introduced into the region. She pointed to the use of symbolism which could be considered Christian, for example, the Latin cross found on the famous Benty Grange helmet, suggesting that its wearer was indeed a Christian, as it was not uncommon for early Christian graves to have grave-goods.

Ozannes paper in Medieval Archaeology , contained some important observations. Firstly, she drew attention to the large number of female barrow burials in the Peak District, suggesting that there was a more equal gender reverence than in later times. Some of the relatively prestigious burials, at Galley Low, Stand Low, White Low and Hurdlow, for example, were all presumed female interments (Ozanne 1962/3, 2628). In terms of identity, Ozanne was quite comfortable to identify the concentration of Anglo-Saxon barrow burials in the Peak as those associated with a people-group mentioned in an obscure Anglo-Saxon document known as the Tribal Hidage . This group was known as the Pecsaetna (sometimes referred to as the Pescsaetan or Pecsaete ), a group allocated 1,200 hides and listed alongside other groups in what we came to refer to as Greater Mercia. One assumption made by Ozanne was that the Pecsaetna and, therefore, the Peak District, were firmly part of the kingdom of Mercia, although we should approach this assumption with extreme caution as this may not have always been the case.