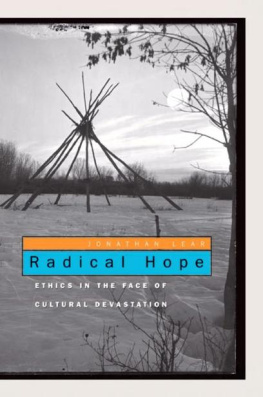

Jonathan Lear - Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation

Here you can read online Jonathan Lear - Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jonathan Lear: author's other books

Who wrote Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

[To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.]

JONATHAN LEAR

For Gabriel

A Peculiar Vulnerability Protecting a Way of Life Gambling with Necessity Was There a Last Coup? Witness to Death Subject to Death The Possibility of Crow Poetry

The End of Practical Reason Reasoning at the Abyss A Problem for Moral Psychology The Interpretation of Dreams Crow Anxiety The Virtue of the Chickadee The Transfonnation of Psychological Structure Radical Hope

The Legitimacy of Radical Hope Aristotle's Method Radical Hope versus Mere Optimism Courage and Hope Virtue and Imagination Historical Vindication Personal Vindication Response to Sitting Bull

FRONTISPIECE Tipis by river. Richard Throssel Collection, American Heritage Center, The University of Wyoming, Ace. 2394.

PAGE xii Plenty Coups. Richard Throssel Collection, American Heritage Center, The University of Wyoming, Ace. 2394.

PAGE 54 Plenty Coups. Richard Throssel Collection, American Heritage Center, The University of Wyoming, Ace. 2394.

PAGE 102 Plenty Coups with adopted daughter (Mary Man With the Beard), photograph by Norman Forsyth. Smithsonian Institution, Office of Anthropology, Bureau of American Ethnology Collection.

[To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.]

SHORTLY BEFORE HE DIED, Plenty Coups, the last great chief of the Crow nation, reached out across the "clash of civilizations" and told his story to a white man. Frank B. Linderman had come to Montana in 1885 as a teenager, and he became a trapper, hunter, and cowboy. He lived in a cabin in the woods near Flathead Lake and was intimately associated with the Crows. From the book he wrote, recounting Plenty Coups's story, it is clear that he and Plenty Coups had become friends. "I am glad I have told you these things, Sign-talker," Plenty Coups says at the end of the book. "You have felt my heart, and I have felt yours. I know you will tell only what I have said, that your writing will be straight like your tongue, and I will sign your paper with my thumb, so that your people and mine will know I told you the things you have written down."' It is a marvelous account of the exploits of a young man growing up at a time when the Crow were still a vibrant tribe of nomadic hunters. Even so, Linderman is reticent about how well he has got to know his subject. In the foreword he says, "I am convinced that no white man has ever thoroughly known the Indian, and such a work as this must suffer because of the widely different views of life held by the two races, red and white. I have studied the Indian for more than forty years, not coldly, but with sympathy; yet even now I do not feel that I know much about him. He has told me many times that I do know him-that I have `felt his heart,' but whether this is so I am not certain."2

But the words that haunt me are not part of Plenty Coups's story, though they do come from his mouth. In an author's note at the end of the book, Linderman says that he was unable to get Plenty Coups to talk about anything that had happened after the Crow were confined to a reservation:

Plenty Coups refused to speak of his life after the passing of the buffalo, so that his story seems to have been broken off, leaving many years unaccounted for. "I have not told you half of what happened when I was young," he said, when urged to go on. "I can think back and tell you much more of war and horse-stealing. But when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere. Besides," he added sorrowfully, "you know that part of my life as well as I do. You saw what happened to us when the buffalo went away."3

After this nothing happened: what could Plenty Coups's utterance mean? If we take him at his word, he seems to be saying that there was an event or a happening-the buffalo's going awaysomething Plenty Coups can refer to as a "this," such that after this, there are no more happenings. Or, to get the temporality correct, Plenty Coups came to see, as he looked back, that there was a moment such that after this, nothing happened. It would seem to be the retrospective declaration of a moment when history came to an end. But what could it mean for history to exhaust itself?

The question is so odd that there is a natural inclination to interpret Plenty Coups as saying something that makes more immediate sense to us. One possibility is to focus on Plenty Coups's claim that after the buffalo went away, "the hearts of my people fell to the ground and they could not lift them up again." As he puts it, "there was little singing anywhere." This might suggest a psychological interpretation: after the buffalo went away, after they were confined to a reservation, the Crow people became depressed; things ceased to matter to them. It was for them as though nothing happened. This psychological interpretation is given added support by the author's account of Plenty Coups adding sorrowfully, "Besides, you know that part of my life as well as I do." In general, it is an astonishing claim for anyone to say that another person knows a part of his adult life as well as he himself does. Although we may be corrected in various ways by others, we take ourselves to have authority when it comes to the narratives of our own lives. Plenty Coups seems to be abdicating this authority when it comes to this period. Indeed, he seems to suggest that anyone-not just the author-who saw what happened when the buffalo went away would be competent to tell that part of his life as well as he could. That is, any competent third-person observer would know all there was to know. This suggests that, according to Plenty Coups, there is no importantly first-person narrative to tell of this period. It is as though there is no longer an I there. This strange thought is made sense of by saying: Plenty Coups is depressed-or he is giving voice to the depression that engulfed his tribe.

This interpretation has the merit of making sense. And it is plausible: Plenty Coups might have been giving voice to a malaise that infected his tribe. The interpretation thus fits what philosophers call the principle of humanity: that we should try to interpret others as saying something true-guided by our own sense of what is true and of what they could reasonably believe.4 But note, we have gained plausibility in interpretation by changing the subject matter. Ostensibly Plenty Coups is making a claim about the world: that after a certain point nothing happened. We have interpreted him as saying something true by taking him to be expressing something about his psyche, and the psyches of his fellow Crow tribesmen. This may fit the Principle of humanity, but there is a question of whether it fits Plenty Coups's humanity. Might he not be giving utterance to a darker thought, one that is more difficult for us to understand? If so, then the psychological interpretation is in too much of a rush. If he is talking about the Crow people becoming depressed, we can understand him in a minute and move on. But if he is talking about happenings coming to an end ... ; how can we interpret him as saying something true?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation»

Look at similar books to Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.