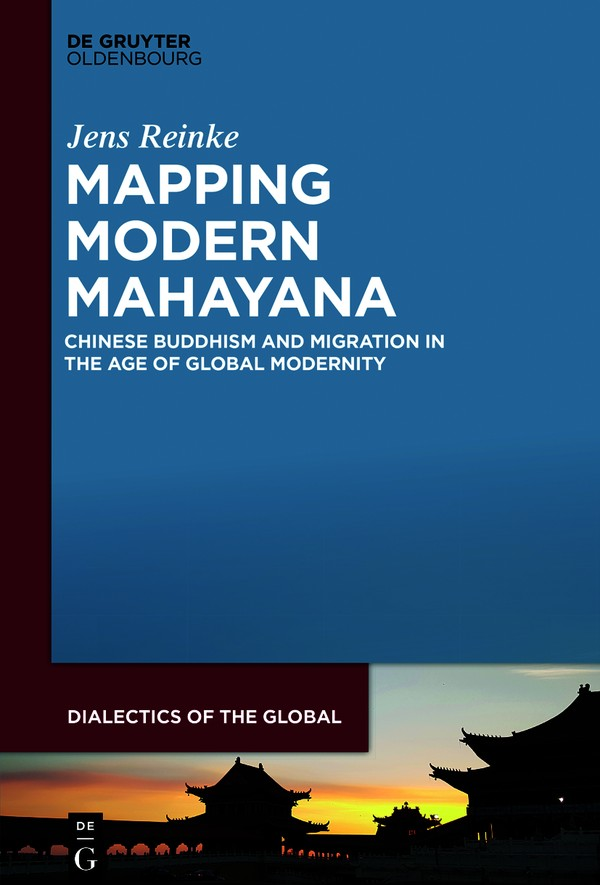

Jens Reinke

Mapping Modern Mahayana

Dialectics of the Global

Edited by

Matthias Middell

Volume

Jens Reinke

Mapping Modern Mahayana

Chinese Buddhism and Migration in the Age of Global Modernity

ISBN 9783110689983

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110690156

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110690200

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Funded with help of the DFG, a product of SFB 1199.

bersicht

Contents

- On the Series

- Acknowledgements

- Abstract

- The Many Transnationalisms of Renjian Buddhism

- Buddhist Border-Crossings during the Age of Colonial Modernity

- Shifting the Centre of Modern Chinese Mahayana

- The Globalization Project of Fo Guang Shan

- Migrating Bodhisattvas and Fo Guang Shan Religious Mobility

- Layers of Ethnic Chinese Migration

- Manoeuvring Diasporic Diversity

- Chineseness Globalized

- Spaces of Buddhist Leisure

- Deterritorializing Nationalized Tradition

- The Move to the Mainland

- Generating Global Pure Lands

- Global Outposts of Renjian Buddhist Education

- Cosmopolitan Goodness

- Purifying the Multitude

- The Religious Ecology of Fo Guang Shan

- Modernist Buddhist Communalism and its Western Other

- Fo Guang Shan and Global China as a Spatial Order

- Multiple Modern Buddhist Religiosities in the Age of Global Modernity

- The Future of Fo Guang Shans Transnationalism

- List of Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Online Sources

- Index

On the Series

Ever since the 1990s, globalization has been a dominant idea and, indeed, ideology. The metanarratives of Cold War victory by the West, the expansion of the market economy, and the boost in productivity through internationalization, digitization and the increasing dominance of the finance industry became associated with the promise of a global trickle-down effect that would lead to greater prosperity for ever more people worldwide. Any criticism of this viewpoint was countered with the argument that there was no alternative; globalization was too powerful and thus irreversible. Today, the ideology of globalization meets with growing scepticism. An era of exaggerated optimism for global integration has been replaced by an era of doubt and a quest for a return to particularistic sovereignty. However, processes of global integration have not dissipated and the rejection of globalization as ideology has not diminished the need to make sense both of the actually existing high level of interdependence and the ideology that gave meaning and justification to it.

The following three dialectics of the global are in the focus of this series:

Multiplicity and Co-Presence: Globalization is neither a natural occurrence nor a singular process; on the contrary, there are competing projects of globalization, which must be explained in their own right and compared in order to examine their layering and their interactive composition.

Integration and Fragmentation: Global processes result in de- as well as reterritorialization. They go hand in hand with the dissolution of boundaries, while also producing a respatialization of the world.

Universalism and Particularism: Globalization projects are justified and legitimized through universal claims of validity; however, at the same time they reflect the worldview and/or interests of particular actors.

Dedicated to the memory of Yeh Wu Su-Zhu

Acknowledgements

It would be impossible to name all those who have supported me during the process of writing this book, but let me nevertheless list some who have been particularly important in making it happen. First and foremost, I am grateful to Fo Guang Shan for permitting me to conduct in-depth ethnographic research at the orders temples and practice centres in Taiwan, the USA, South Africa, and the PRC. I am indebted to all the orders monastics and lay supporters who so generously offered me their valuable insights into the orders global development. I owe too many of them a debt of gratitude and it would be impossible to name them all. I am particularly grateful to Ven. Huifang , Ven. Huidong , Ven Miaoguang , Ven. Miaoshiang , Ven. Miaoyi , Ven. Miaomin , and Matt Orsborne. I also want to express my gratitude to Jane Iwamura, Victor Gabriel, and Vanessa Karam at the University of the West for their invaluable advice and encouragement.

This book is based on my doctoral thesis written at the Collaborative Research Centre (SFB) 1199: Processes of Spatialization under the Global Condition at Leipzig University. I would especially like to thank the centre for so generously providing the funding for the research for this book, which allowed me to carry out fieldwork on four continents. Most of all, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Philip Clart, without whose continuous support I would have not been able to complete this book. I am very grateful for his invaluable advice and feedback. His patient guidance has helped me not only through the process of writing up but also during my time in the field. His kind and ever constructive attitude towards all his students is a quality I would like to emulate in the future. Furthermore, I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my second advisor Andr Lalibert. His singular perspective, which examines modern Taiwanese Buddhism within the broader political and societal context of East Asia, had been a source of inspiration long before I met him in person. I benefited immensely from our conversations during his time in Leipzig.

If it were not for the training I received at the Graduate Institute of Religious Studies at National Chengchi University , I would never have been able to properly research Taiwanese religiosities. A special thank you goes to my MA advisor Li Yu-chen , who taught me not only most of what I know about Chinese Buddhism but also even more importantly the subtleties of conducting ethnographic research in the field. A sincere thank you goes to my MA dissertation committee members Chen Chien-huang and Hsieh Shu-wei for their invaluable advice on my thesis, but also for all I have learned from them about the history of Chinese religions. I very much regret that the late Tsai Yan-zen did not live to see this book completed; he was a wonderful teacher. I am also very grateful to Tsai Yuan-lin , who taught one of the first classes I took at National Chengchi University. His class on religion and globalization was inspirational, and I am still in the field. While at Chengchi University, I also had the opportunity to meet Miriam Levering and her late partner Mary E. Donovan. I miss our excursions into the culinary worlds of northern Taiwan. Furthermore, I want to express my deep thanks to Huang Hou-min from the Sociology Department at National Chengchi University , who, through his demanding yet inspirational teaching style, conveyed to me the foundations of sociological theory.