The Mishap Lineage

TRANSFORMING CONFUSION INTO WISDOM

Chgyam Trungpa

Edited by Carolyn Rose Gimian

SHAMBHALA

BOSTON & LONDON

2010

Dedicated to the people of Surmang

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

2009 by Diana J. Mukpo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A portion of the authors proceeds from this book are being donated to the Konchok Foundation, which supports the rebuilding of the Surmang monasteries, the education of the Twelfth Trungpa, and other projects in East Tibet.

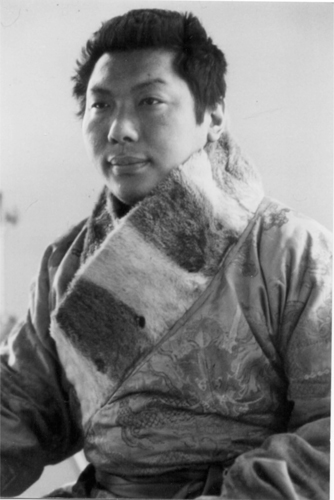

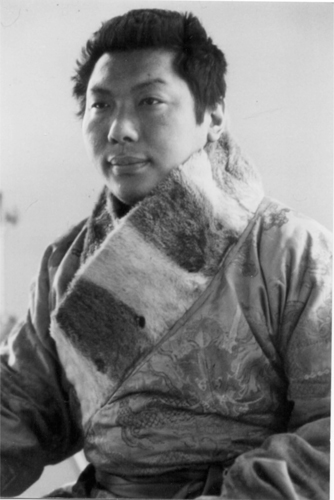

Frontispiece: Chgyam Trungpa in the robes of the Tenth Trungpa. Photo by Martin Janowitz.

The Tibetan symbol that appears on the cover and chapter openers of this book is called an Evam. Evam is the personal seal of the Trungpa tulkus. It is a symbol of the unity of the feminine principle of space and wisdom, E, with the masculine principle of compassion and skillful means, Vam.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Trungpa, Chgyam, 19391987.

The mishap lineage: transforming confusion into wisdom / Chgyam Trungpa; edited by Carolyn Rose Gimian.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2124-8

ISBN 978-1-59030-713-7

1. Drun-pa lamasBiography. 2. Religious lifeKar-ma-pa (Sect) I. Gimian, Carolyn Rose. II. Title.

BQ7682.9.A2T78 2009

294.39230922dc22

[B]

2009008425

Contents

Editors Preface

THE MISHAP LINEAGE: Transforming Confusion into Wisdom is Chgyam Trungpas personal reflection on his lineage, the lineage of Trungpa tulkus, or incarnate teachers, which began in Tibet in the fifteenth century. Chgyam Trungpa himself, who was born in Tibet in 1940, was the Eleventh Trungpa. In this book, Trungpa Rinpocherinpoche is a title for reincarnate teachers that means precious oneis not so much documenting the history of the teachers in the lineage as he is informing our own contemporary experience with the myths or stories of his predecessors. Here, stories from the lives of the Trungpas are a point of departure for the discussion of the principles and the experiences that guide a practitioners journey on the path. These discussions are also related to how he viewed the introduction of the Buddhist teachings in North America and his hopes for their future.

He uses the historical framework to help us understand how we can relate to the idea of lineage and community in the modern context of a spiritual journey. What is the nature of lineage? How can we, as twenty-first-century practitioners, connect with the stories of practitioners experiences hundreds of years ago? Does their experience apply to us? Is it true, is it relevant, is it real? These are questions the reader can explore in this volume. Perhaps some of the questions will be answered. Perhaps some will remain as fuel for the journey. That would certainly be in keeping with how the author taught. He was much more interested in awakening curiosity than in providing certainty, and the style of the presentation here is in keeping with that.

The idea of the Mishap Lineage, encountering and sometimes even inviting constant mishaps and then using them as the ground for the next stage of development on the path, is introduced here as a defining characteristic of the Kagy lineage, and particularly of the line of the Trungpas. The theme of mishaps and the lineage of mishaps comes up over and over. So far as I was able to uncover, there is no term for Mishap Lineage in Tibetan. Chgyam Trungpa gave us dynamic translations for key Buddhist terms in the English language, many of which have shaped the view of practice and the Buddhist path in America. Beyond that, he coined new phrases that have no equivalent in Tibetan or Sanskrit, such as spiritual materialism, meditation in action, andnow we learnMishap Lineage. These terms may be among the most important concepts he presented; clearly, they are particularly applicable to Buddhism in America. The concept of the Mishap Lineage also reflects the personal quality of his own journey. His coming to the West only occurred because of the mishap of the Chinese invasion of Tibet. His coming from England to America only took place because of many mishaps that occurred in England. He himself feasted on mishaps, using them as fuel and food for the continuing journey rather than shying away. The Mishap Lineage was chosen as the title for this book because this principle seems to resonate so strongly with our experience of Buddhist practice in the West. The seminar that was the basis for much of the material in this book, as far as this editor knows, is the first place where this concept was introduced.

Chgyam Trungpa died more than twenty years ago, on April 4, 1987, yet his teachings are still practiced today by thousands, many of whom never met him, and read each year by tens of thousands more. There is a growing appreciation for the central role that he played in bringing the Buddhist teachings to the West, in particular his pivotal role in establishing the tradition of the Practicing Lineage in America. This book is an offering to him, the teachers of his lineage, and to his students, both those who knew him and studied with him personally, as well as those who encounter him in his written work or are practicing now in his tradition, applying his teachings in their practice of meditation, following the path he laid out.

and Wenchen Nunnery, near Kyere, where the nuns practice many of Rinpoches teachings in their retreats. After all, as Rinpoche says in the last talk: Surmang is Trungpa. Trungpa is Surmang. It is where most of the events described in this volume took place. And we should not forget that without Surmang and the mishaps that affected Tibet, there would never have been a Chgyam Trungpa in America. We owe these people and this place an enormous debt.

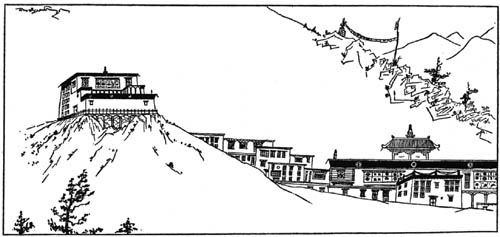

Surmang Dtsi Tel. Drawing by Chgyam Trungpa. |

In December 1975, when Rinpoche presented the Mishap Lineage seminar (originally titled The Line of the Trungpas seminar) that is the basis for this book, he had little reason to believe that his dharma lineage had survived at Surmang. Rinpoche began his journey out of Tibet in 1959, after receiving a report of the sacking of the monastery. His bursar described to him how the sacred remains of the Tenth Trungpa were desecrated by the Chinese. The bursar, having cremated the remains, brought them to Rinpoche. Understandably, Trungpa Rinpoche saw little future for the dharma in Tibet. Many terma teachings that he had discovered at Surmang were destroyed, as far as he knew, as well as other practice texts and writings. He rarely spoke about these teachings, perhaps in part because he saw no chance that they would be recovered.

Toward the end of his life, Trungpa Rinpoche received letters and other communications from Tibet, including a letter from his mother, and he expressed a desire to visit Surmang by helicopter (since he was not well enough to get there by other means), but this was not to be. Following his death, a number of his students traveled to Surmang and began to reestablish relationships there.

Next page