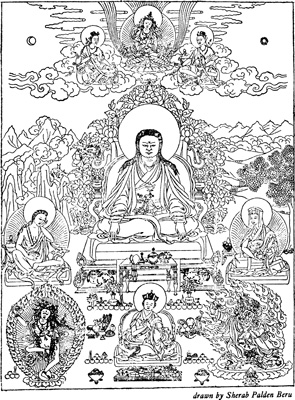

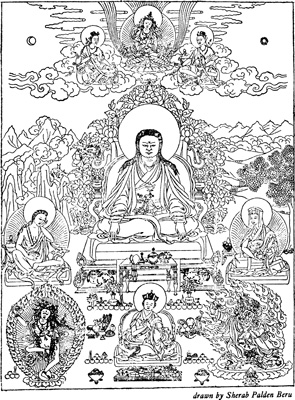

Center: Marpa the Translator, father of the Kagy school.

Clockwise from top: Vajradhara Buddha with two Indian gurus, Gampopa, Mahakala (the Protector), Karmapa, Vajra Yogini (female divinity), and Milarepa.

DRAWN BY SHERAB PALDEN BERU.

BORN IN TIBET

by

CHGYAM TRUNGPA

The eleventh TRUNGPA TULKU

as told to

ESM CRAMER ROBERTS

With Forewords by

THE SAKYONG MIPHAM RINPOCHE

and

MARCO PALLIS

Fourth Edition

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2010

To my Mother and motherland

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

1966 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Epilogue 1977 by Chgyam Trungpa

Foreword to the 1995 Edition 1995 by Diana Mukpo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Library of Congress catalogues the 1985 edition of this book as follows:

Trungpa, Chgyam, 1939

Born in Tibet.

Reprint. Originally published: Boulder, Colo.: Shambhala, 1977, c1966.

Includes index.

1. Trungpa, Chogyam, 1939. 2. LamasChinaTibetBiography. I. Roberts, Esm Cramer. II. Title.

BQ990.R867A33 1985 294.3 923 0924 [B] 85-8174

eISBN 978-0-8348-2130-9

ISBN 0-87773-333-3

ISBN 0-394-74219-2

ISBN 1-57062-116-0

ISBN 1-57062-714-2

CONTENTS

Foreword to the 1995 Edition

W HEN I THINK back upon my fathers life, it amazes me how much he accomplished in such a short time. He was only forty-eight years old when he passed away, but within that time, the experiences he had and the people he encountered were as varied and rich as if he had lived for hundreds of years.

Often people would ask him how he was able to adapt to so many diverse cultures, and how he was able to deal with the tremendous hardships of his life. Always his answer would be that it was due to the rigorous traditional training and education that he received in Tibet while he was young. It might appear to the reader that the Tibet of Chgyam Trungpas youth was medieval; it seems so distant from todays modern world, and so harsh. Ironically, however, it was that very training, with its simplicity and realness, that gave him the foundation that enabled him to relate with this modern world.

My father had two distinct roles in his life, corresponding with the periods of his life spent in the East and the West. During the first part of his life, since he was recognized as the incarnation of a famous teacher, people had high expectations of him. Many of the lamas and monks at the monastery were quite concerned that he be able to fit into his traditional role and continue the work of his predecessor. He very much had to fulfill the ambitions of the monastic community, as well as those of the laypeople of his religion.

Once he left Tibet, his role was quite differentalmost totally the opposite. In the West, very few people knew much about Buddhism as a whole, and they knew even less about the role of a lama, a spiritual teacher. People had little basis for any kind of expectations. In many ways, this was incredibly liberating for Chgyam Trungpa, and in fact it enabled him to become one of the most prominent Buddhist teachers of his time. His unique gift was that he was able to synthesize the ancient wisdom of Buddhism and transmit it to the West in a clear and concise way that was both meaningful and refreshingso much so that a new generation of Western practitioners was born.

Born in Tibet is a unique book, one that I personally have always loved to read. It is not just a historical document, a book about Tibetan culture, but it reveals many subtleties of what that life was actually like. It shows the spiritual development of teacher and disciple, and it illustrates the humanness that everyone possesses, regardless of culture, and the politics that come about from that.

Even though my father was not particularly a nostalgic person, he had tremendous pride in his Tibetan heritage, which he transmitted to me in various ways. Occasionally in the middle of the night, we would prepare bandit soup together. This was one of his favorite Tibetan delicacies, which was simply raw meat with hot water poured over it.

Knowing the tremendous hardships and challenges that confronted Chgyam Trungpa, and how he was able to overcome them through his courage, humor, and his faith in the spiritual disciplines of Tibet, I have always found this book inspiring. I hope that you too may be inspired by his example, and that this book will continue to benefit numberless beings.

THE SAKYONG MIPHAM RINPOCHE

November 25, 1994

Karm Chling

Foreword to the 1977 Edition

S TORIES OF ESCAPE have always enlisted the sympathy of normal human beings; no generous heart but will beat faster as the fugitives from civil or religious persecution approach the critical moment that will, for them, spell captivity or death, or else the freedom they are seeking. The present age has been more than usually prodigal in such happenings, if only for the reason that in this twentieth century of ours, for all the talk about human rights, the area of oppression, whether as a result of foreign domination or native tyranny, has extended beyond all that has ever been recorded in the past. One of the side effects of modern technology has been to place in the hands of those who control the machinery of government a range of coercive apparatus undreamed of by any ancient despotism. It is not only such obvious means of intimidation as machine guns or concentration camps that count; such a petty product of the printing press as an identity card, by making it easy for the authorities to keep constant watch on everybodys movements, represents in the long run a still more effective curb on liberty. In Tibet, for instance, the introduction of such a system by the Chinese Communists, following the abortive rising of 1959, and its application to food rationing has been one of the principal means of keeping the whole population in subjection and compelling them to do the work decreed by their foreign overlords. Formerly Tibet was a country where, though simple living was the rule, serious shortage of necessities had been unknown: Thus, one of the most contented portions of the world has been reduced to misery, with many of its people, like the author of the present book, choosing exile rather than remain in their own homes under conditions where no man, and especially no young person, is any longer allowed to call his mind his own.

Hostile propaganda, playing on slogan-ridden prejudice, has made much of the fact that a large proportion of the peasantry, in the old Tibet, stood in the relation of feudal allegiance to the great land-owning families or also to monasteries endowed with landed estates; it has been less generally known that many other peasants were small holders, owning their own farms, to whom must be added the nomads of the northern prairies, whose lives knew scarcely any restrictions other than those imposed by a hard climate and by the periodic need to seek fresh pasturage for their yaks and sheep. In fact all three systems, feudal tenure, individual peasant proprietorship and nomadism have always existed side by side in the Tibetan lands; of the former all one need say is that it naturally would depend, for its effective working, on the regular presence of the landowner and his family among their own people; in any such case, absenteeism is bound to sap the essential human relationship, bringing other troubles in its train. In central Tibet a tendency on the part of too many of the secular owners to stop in Lhasa, with occasional outings down to India, had latterly become apparent and this was to be accounted a danger sign; further east, in the country of Kham to which the author belongs, unimpaired patriarchal institutions prevailed as of old and no one wished things otherwise. Of the country as a whole it can be said that, generally speaking, the traditional arrangements worked in such a way that basic material needs were adequately met, life was full of interest at every social level, while the Buddhist ideal absorbed everyones intellectual and moral aspirations at all possible degrees, from that of popular piety to spirituality of unfathomable depth and purity. By and large, Tibetan society was a unanimous society in which, however, great freedom of viewpoint prevailed and also a strong feeling for personal freedom which, however, did not conflict with, but was complementary to, a no less innate feeling for order.

Next page