Armstrong - A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam

Here you can read online Armstrong - A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1993, publisher: Ballantine Books, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Armstrong: author's other books

Who wrote A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

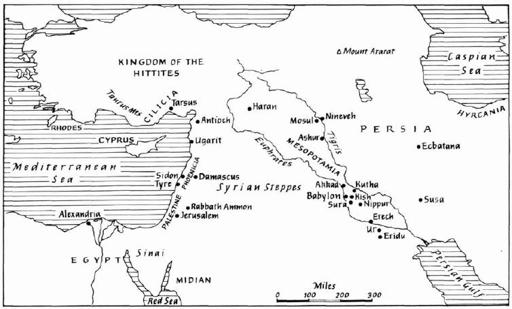

The Ancient Middle East

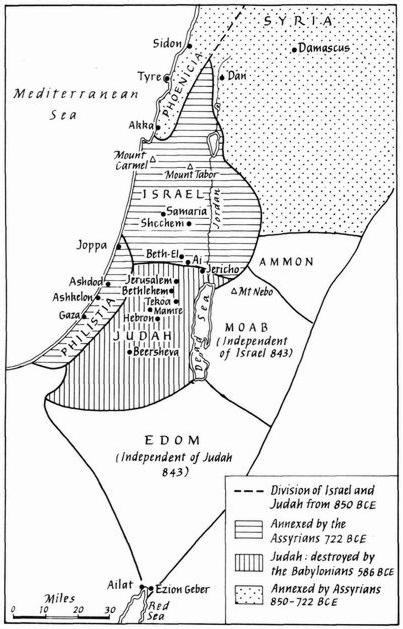

The Kingdom of Israel and Judah 722-586 BCE

As a child, I had a number of strong religious beliefs but little faith in God. There is a distinction between belief in a set of propositions and a faith which enables us to put our trust in them. I believed implicitly in the existence of God; I also believed in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the efficacy of the sacraments, the prospect of eternal damnation and the objective reality of Purgatory. I cannot say, however, that my belief in these religious opinions about the nature of ultimate reality gave me much confidence that life here on earth was good or beneficent. The Roman Catholicism of my childhood was a rather frightening creed. James Joyce got it right in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: I listened to my share of hell-fire sermons. In fact Hell seemed a more potent reality than God, because it was something that I could grasp imaginatively. God, on the other hand, was a somewhat shadowy figure, defined in intellectual abstractions rather than images. When I was about eight years old, I had to memorise this catechism answer to the question, 'What is God?': 'God is the Supreme Spirit, Who alone exists of Himself and is infinite in all perfections.' Not surprisingly, it meant little to me and I am bound to say that it still leaves me cold. It has always seemed a singularly arid, pompous and arrogant definition. Since writing this book, however, I have come to believe that it is also incorrect.

As I grew up, I realised that there was more to religion than fear. I read the lives of the saints, the metaphysical poets, T. S. Eliot and some of the simpler writings of the mystics. I began to be moved by the beauty of the liturgy and, though God remained distant, I felt that it was possible to break through to him and that the vision would transfigure the whole of created reality. To do this I entered a religious order and, as a novice and a young nun, I learned a good deal more about the faith. I applied myself to apologetics, scripture, theology and church history. I delved into the history of the monastic life and embarked on a minute discussion of the Rule of my own order, which we had to learn by heart. Strangely enough, God figured very little in any of this. Attention seemed focused on secondary details and the more peripheral aspects of religion. I wrestled with myself in prayer, trying to force my mind to encounter God but he remained a stern taskmaster, who observed my every infringement of the Rule, or tantalisingly absent. The more I read about the raptures of the saints, the more of a failure I felt. I was unhappily aware that what little religious experience I had, had somehow been manufactured by myself as I worked upon my own feelings and imagination. Sometimes a sense of devotion was an aesthetic response to the beauty of the Gregorian chant and the liturgy. But nothing had actually happened to me from a source beyond myself. I never glimpsed the God described by the prophets and mystics. Jesus Christ, about whom we talked far more than about 'God', seemed a purely historical figure, inextricably embedded in late antiquity. I also began to have grave doubts about some of the doctrines of the Church. How could anybody possibly know for certain that the man Jesus had been God incarnate and what did such a belief mean? Did the New Testament really teach the elaborate - and highly contradictory - doctrine of the Trinity or was this, like so many other articles of the faith, a fabrication by theologians centuries after the death of Christ in Jerusalem?

Eventually, with regret, I left the religious life and once freed of the burden of failure and inadequacy, I felt my belief in God slip quietly away. He had never really impinged upon my life, though I had done my best to enable him to do so. Now that I no longer felt so guilty and anxious about him, he became too remote to be a reality. My interest in religion continued, however, and I made a number of television programmes about the early history of Christianity and the nature of the religious experience. The more I learned about the history of religion, the more my earlier misgivings were justified. The doctrines that I had accepted without question as a child were indeed man-made, constructed over a long period of time. Science seemed to have disposed of the Creator God and biblical scholars had proved that Jesus had never claimed to be divine. As an epileptic, I had flashes of vision that I knew to be a mere neurological defect: had the visions and raptures of the saints also been a mere mental quirk? Increasingly, God seemed an aberration, something that the human race had outgrown.

Despite my years as a nun, I do not believe that my experience of God is unusual. My ideas about God were formed in childhood and did not keep abreast of my growing knowledge in other disciplines. I had revised simplistic childhood views of Father Christmas; I had come to a more mature understanding of the complexities of the human predicament than had been possible in the kindergarten. Yet my early, confused ideas about God had not been modified or developed. People without my peculiarly religious background may also find that their notion of God was formed in infancy. Since those days, we have put away childish things and have discarded the God of our first years.

Yet my study of the history of religion has revealed that human beings are spiritual animals. Indeed, there is a case for arguing that Homo sapiens is also Homo religiosus. Men and women started to worship gods as soon as they became recognisably human; they created religions at the same time as they created works of art. This was not simply because they wanted to propitiate powerful forces but these early faiths expressed the wonder and mystery that seems always to have been an essential component of the human experience of this beautiful yet terrifying world. Like art, religion has been an attempt to find meaning and value in life, despite the suffering that flesh is heir to. Like any other human actitivity, religion can be abused but it seems to have been something that we have always done. It was not tacked on to a primordially secular nature by manipulative kings and priests but was natural to humanity. Indeed, our current secularism is an entirely new experiment, unprecedented in human history. We have yet to see how it will work. It is also true to say that our Western liberal humanism is not something that comes naturally to us; like an appreciation of art or poetry, it has to be cultivated. Humanism is itself a religion without God - not all religions, of course, are theistic. Our ethical secular ideal has its own disciplines of mind and heart and gives people the means of finding faith in the ultimate meaning of human life that were once provided by the more conventional religions.

When I began to research this history of the idea and experience of God in the three related monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, I expected to find that God had simply been a projection of human needs and desires. I thought that 'he' would mirror the fears and yearnings of society at each stage of its development. My predictions were not entirely unjustified but I have been extremely surprised by some of my findings and I wish that I had learned all this thirty years ago, when I was starting out in the religious life. It would have saved me a great deal of anxiety to hear - from eminent monotheists in all three faiths - that instead of waiting for God to descend from on high, I should deliberately create a sense of him for myself. Other Rabbis, priests and Sufis would have taken me to task for assuming that God was - in any sense - a reality 'out there'; they would have warned me not to expect to experience him as an objective fact that could be discovered by the ordinary rational process. They would have told me that in an important sense God was a product of the creative imagination, like the poetry and music that I found so inspiring. A few highly respected monotheists would have told me quietly and firmly that God did not really exist - and yet that 'he' was the most important reality in the world.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam»

Look at similar books to A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A History Of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.