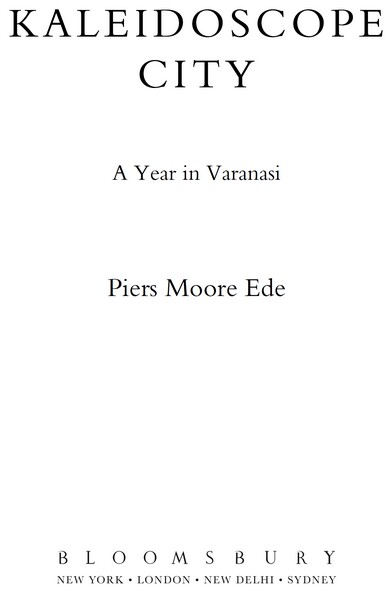

For Lucy, this ones for you

Contents

Kashi is the whole world they say. Everything on earth that is powerful and auspicious is here, in this microcosm. All of the sacred places of India and all of her sacred waters are here. All of the Gods reside here, attracted by the brilliance of the City of Light. All of the eight directions of the compass originated here, receiving jurisdiction over the sectors of the universe. And all of time is here, for the lords of the heavenly bodies which govern time are grounded in Kashi.

Diana Eck, Banaras: City of Light

Perhaps for all of us there is a country, and within that a single place, in which some essential element of the world is illuminated for the first time. Sitting down on a park bench in a beam of sunlight, or lost in the cacophony of a spice market, it comes to us that we have never been this vibrantly, persuasively alive. Our heart centre as the Indian yogis like to call it is aflame with the wonder of all things.

I first came to Varanasi when I was twenty-five, en route for Nepal through northern India, and with very little idea about the city other than it was supposed to be interesting, and that it made a convenient resting place for a few days before I continued my journey. India had already begun to work her magic on me, but it was in Varanasi (known as Kashi in the scriptures, or more recently Banaras ) that the full possibility of what India might be seemed to announce itself. Here was a vast experiment in human cohabitation that had been going on for five thousand years: a river city containing every facet of humanity, every creed, colour, caste, both astonishing beauty and the most harrowing ugliness and desolation. Here was the madness of India, as well as its wisdom, the sublime poetry of its spiritual traditions and the dirty imbalance of corruption. Here were Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Christians, Jains and Sikhs, as well as infinite sects pre-dating any of these major traditions, but which persisted happily within the larger whole. All of it combined as the city itself: one entity, a composite of spirit and form.

Until then I had supposed India was essentially unfathomable: it was too fast, too swiftly changing to yield to any categorisation. In Varanasi, however, I found a city whose spirit seemed to denote the whole. On that first trip, even from my fairly cursory explorations, it seemed abundantly clear that there was something unique about the place, an energetic quality, a feeling that spoke in the body long before it appeared as thought. There was an intensity to the alleys and the dust, which was part of the makeup of the citizens themselves, the most passionate, lively people Id ever encountered. Even after leaving it behind, the resonance of Banaras kept returning to me like some haunting snatch of music. I wanted to hear that music again, let it play upon my ears for a while, until it revealed its secrets.

The following winter I returned for a month, and the winter after that for three months. At first, my reasons for being there remained unclear to me I studied yoga and meditation, walked for hours, spent long days reading at the library Krishnamurti had set up at Raj Ghat, sometimes taking a boat ride home, a blissful hour in which the whole sweep of the river front would pass before me. I was in my mid-thirties, still restless. Why I should find answers here was anyones guess, and yet a certain intuition kept my ear to the ground. As with the thousands of pilgrims who arrived here on any given day, I was hoping the city herself would respond.

Finally, the opportunity came to return for a longer period, perhaps a year. Here now, at last, I felt I might cease to be an outsider and penetrate to the citys heart. I returned during the last burning days of summer, the Ganga lower than I had ever seen it owing to a poor monsoon, the heat shimmering off the flat plains of Uttar Pradesh at over 40 degrees. With one small bag of clothes, no camera, and the germ of an idea to write about my experiences, I went to Assi Ghat, which has long been the haunt of foreign residents. The word ghat refers to the flights of stone steps descending the banks of the Ganga into water: there are nearly a hundred in Varanasi, with Assi the southernmost. Because of this, it has retained an open village-like feel, bucolic at its edges, until very recently.

Looking back over my notes from those first days, I notice the shock and exhaustion of my re-entry: dust-red eyes from whizzing rickshaw rides, ears resounding with the blasts of incessant car horns, mind spinning with the velocity of it all, which somehow, I dont know how, Id forgotten. As any quantum physicist will tell you, all we are is energy, but in Varanasi that energy seems more highly charged: spinning faster, amplified somehow so that basic human tasks such as simply going to buy rice become shattering experiences of navigating two-hour traffic jams, throwing oneself against the side of an alley to avoid being crushed by a roaring Tata motorbike, or weaving between unruly cattle in the course of crossing the street. The crush of human numbers, the crumbling medieval architecture built upon and compressed by concrete structures, the hissing charge of frayed electric wires used as ropes by monkey troupes, the appalling pollution and a thousand other environmental factors combine to make the city an alchemists crucible, transmuting all who live there. Should you, after returning home across the city, wipe your face with a white cloth it will be stained black from the traffic fumes. Your lungs burn, your eyes stream, your stomach purges, and yet despite all this your spirit soars.

Within a week or so Id found a place to live: two rooms at the top of a supremely ugly custard-yellow concrete building right on the edge of the river. My landlord, Khado Yadav, lived with his wife, son and grandchildren on the ground floor, along with a legion of mice who would scuttle about, searching for fallen crumbs, while the family watched soap operas on television. During one of our first conversations, while Mr Yadav examined my potential as a likely tenant from his armchair, I gained a useful lesson by observing how the family simply let the mice be, utterly unconcerned by their presence. This was the key, perhaps, to surviving the city: an equanimous acceptance for a foreigner, easier said than done.

After the necessary haggling over the rent, Mr Yadav, a little creaky in his early seventies, and wearing a dal-stained white vest and lungi, showed me my quarters two rooms with bare concrete floors, and with only mesh windows, painted several generations before with a cobalt-blue now flaking paint. An iron key that might have unlocked a castle door clicked open the padlock. The only piece of furniture of note was a bed, built in the Indian style of wooden planks. In short, the place was perfect: cheap to inhabit, authentically Spartan, and with a view from one side over the Ganga herself. I could use the familys own bucket shower for washing, and if things needed to be dried, there was the rooftop he pointed a digit vertically which I was welcome to make use of.

I moved in soon after, purchasing the essentials of a gas ring, a few pans, a cast-iron tava a convex disc-shaped griddle for cooking chapattis, and a mosquito net. I arranged my single shelf with a few scholarly tomes on the city, a metal beaker for drinking water, notebook and pens, a postcard image of the great saint Sri Ramana Maharshi, as well as certain concessions to modernity, such as my laptop. As I lay down on my bed that first night, the warm wind streaming in through the rusted window mesh, I could hear rhesus macaques and tussling crows on the neighbouring roof. The months stretched ahead like an open promise, the river flowed past my window carrying the first night-time oil lamps, floating prayers cast out into the twilight.

Next page