Justin Welby - The Power of Reconciliation

Here you can read online Justin Welby - The Power of Reconciliation full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Bloomsbury, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Power of Reconciliation

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Power of Reconciliation: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Power of Reconciliation" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Power of Reconciliation — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Power of Reconciliation" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To my mother Jane Williams, my stepfather the late Charles Williams, and to my grandmother Iris Portal, from whom I learned curiosity, presence and imagination.

To the Norton Group and others who pray for me.

Contents

God then,

encompassing all things, is

defenseless? Omnipotence

has been tossed away, reduced

to a wisp of damp wool?

And we

frightened, bored, wanting

only to sleep till catastrophe

has raged, lashed, seethed and gone by without us,

wanting then

to awaken in quietude without remembrance of agony,

we who in shamefaced private hope

had looked to be plucked from fire and given

a bliss we deserved for having imagined it,

is it implied that we

must protect this perversely weak

animal, whose muzzles nudgings

suppose there is milk to be found in us?

Must hold to our icy hearts

a shivering God?

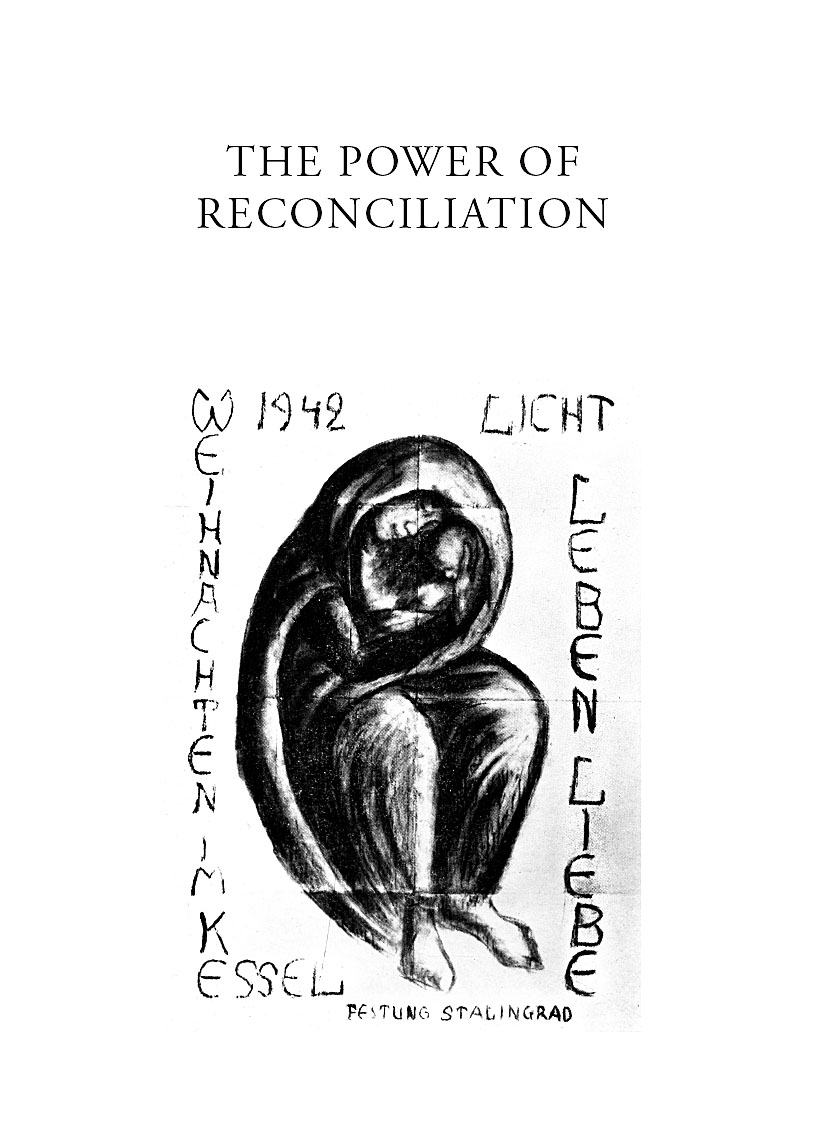

The woman circles the baby in a shawl, enveloping them both. Both faces are barely visible. Her arms and body are the circling not of fear and despair but of love and faith. Were it not for the arms of the mother, the child would be exposed, vulnerable, condemned to die by weather and cruelty. She puts her body between him and the world.

Outside the dug-out where the picture an ikon of Mary and Jesus is pinned to a mud wall, the reality is of a frozen hell. It is December 1942, Stalingrad. The German advance of the previous eighteen months had taken them to the edge of the Volga. Here they were stopped and for months the fighting swayed to and fro, until the German forces were turned by Russian advances from besiegers to besieged. The conditions were appalling, the loss of life enormous, the suffering of soldiers and civilians immense, made worse by the callousness of the supreme commanders of both sides.

Yet, amid this frozen killing ground there were some places of hope. Lieutenant Kurt Reuber, pastor and physician with the encircled German army, having drawn the ikon, used it as a place for soldiers to pray and meditate, to find something of the love of family, of their mothers care. He died in 1944, a prisoner in Russia, together with two-thirds of his companions captured in January 1943 at Stalingrad. The ikon escaped on virtually the last flight out. The original is displayed in the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, Berlin, while copies now hang in the cathedrals of Berlin, Coventry and Kazan, Volgograd, as a sign of the reconciliation between Germany and its enemies: the United Kingdom and Russia.

Around the margin are included three words, Licht, Leben, Liebe , light, life, love. The light shone in the with scenes of horror that are numbing. The ikon tells of hope, of peace, of Gods abundance in Jesus Christ and of human partnership in the ancient dream of swords into ploughshares. It calls for peace.

There is something very remarkable about the ikon. It seems to create a dream of peace in a world of war. It calls from another world, one full of suffering, but one in which a woman and her child could conceivably survive. Its marginal words tell of warmth from light and love and of hope of life. It calls out for help and also reassures because the child is the Christ-child, the baby of Bethlehem, whose existence was menaced from his birth until his death and who yet rose from the dead and decisively changes the world. For me the ikon calls out, Have mercy, we want peace on the one hand, and on the other, Have hope, here is peace.

Is this infant fragility really Gods answer to the power of war and hatred, to the darkness of sin? Surely God may as well have lit a candle in a hurricane.

The human eye sees a mother in thin peasant clothes cradling a baby who would die so quickly if abandoned, perhaps in minutes: St John tells us this is the Word through whom all things were made.

Yet in the world busy human eyes are too preoccupied and overlook the mother, doubtless walked past each day in every great city on earth, on every battlefield and in every refugee camp. We who are safe avert our gaze from such sadness and suspect a trick: St John says this is an inextinguishable light that reveals the face of God.

That contrast remains true. I ring a bishop in Mozambique after a bitter and bloody attack from ISIS. I speak to another in South Sudan as the refugee camp in which he lives is shelled by rebel forces. I get a message from the wife of a close friend engaging in peacebuilding, Ebola resisting and COVID care in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), to say he has died from the virus.

I sit by someone weeping at the breakup of a relationship, or the estrangement of a child. I pray by the bed of a woman dying of COVID-19. A letter comes blaming the Church, blaming me, for failing to prevent the abuse of young people.

In all these places it is futile and uncaring at that moment to speak of reconciliation. Can there be change amid such suffering? Surely the tide of history will wash away any sandcastles of peace? Surely the darkness will win?

Yet for one very simple reason I turn back to the ikon. For this child and his obedient and self-giving mother, who endured so much more than can be imagined, is truly light, life, love. In him God is revealed in all his forceless glory and power. This is the God who draws worship not by compulsion but by fragility that is real and deathless.

The shivering child Jesus he certainly shivered and his sheltering mother are Gods call to us that he speaks as an adult, Blessed are the peacemakers for they shall be called children of God (Matthew 5.9). God has set the pattern and the means. The pattern is vulnerability. The means is sacrifice. This baby will live some thirty-three years and die on a cross with this mother unable to hold more than his dead, tortured body. This baby will be the cornerstone of stories of peace, the foundation of a community that is more diverse than any other on earth. It will be a community that rejoices in the abundance of diversity and seeks, because of this child, to learn to love one another and the whole world. It will be an example of failure too often, but sometimes the light of life and hope. That community will be filled with the Spirit of this child so that, at its best, no sacrifice is too great to ensure that Gods choice of abundance is poured into the world.

This fragility is reconciliation incarnate, made flesh. Reconciliation must be made flesh if it is going to be real. It must transform the lives of the weak, it must protect and it must go on trying even when it fails again and again. To give up is to accept, as though through scientific experiment, that the will to power of so many people is an undeniable absolute of being human. The will to power, the formation of identity through defining ourselves as what we are not, or by targeting another group as enemies, has become acceptable since the early twentieth century as being what makes for success, satisfaction, virtue.

With the will to power, coming from within ourselves, from pride and desire, there is no space for the ordinarily human, for the good community. Power hates weakness, and boasts that it never explains, never apologizes. It cannot abide reconciliation, which requires listening to another view, even putting oneself or ones group in the shoes of the other. Power will neither offer nor receive forgiveness. As a result, the enemy must be cancelled, perhaps physically, but certainly emotionally and if possible in public esteem.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Power of Reconciliation»

Look at similar books to The Power of Reconciliation. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Power of Reconciliation and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.