Sommaire

Pagination de l'dition papier

Guide

InterVarsity Press

P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426

ivpress.com

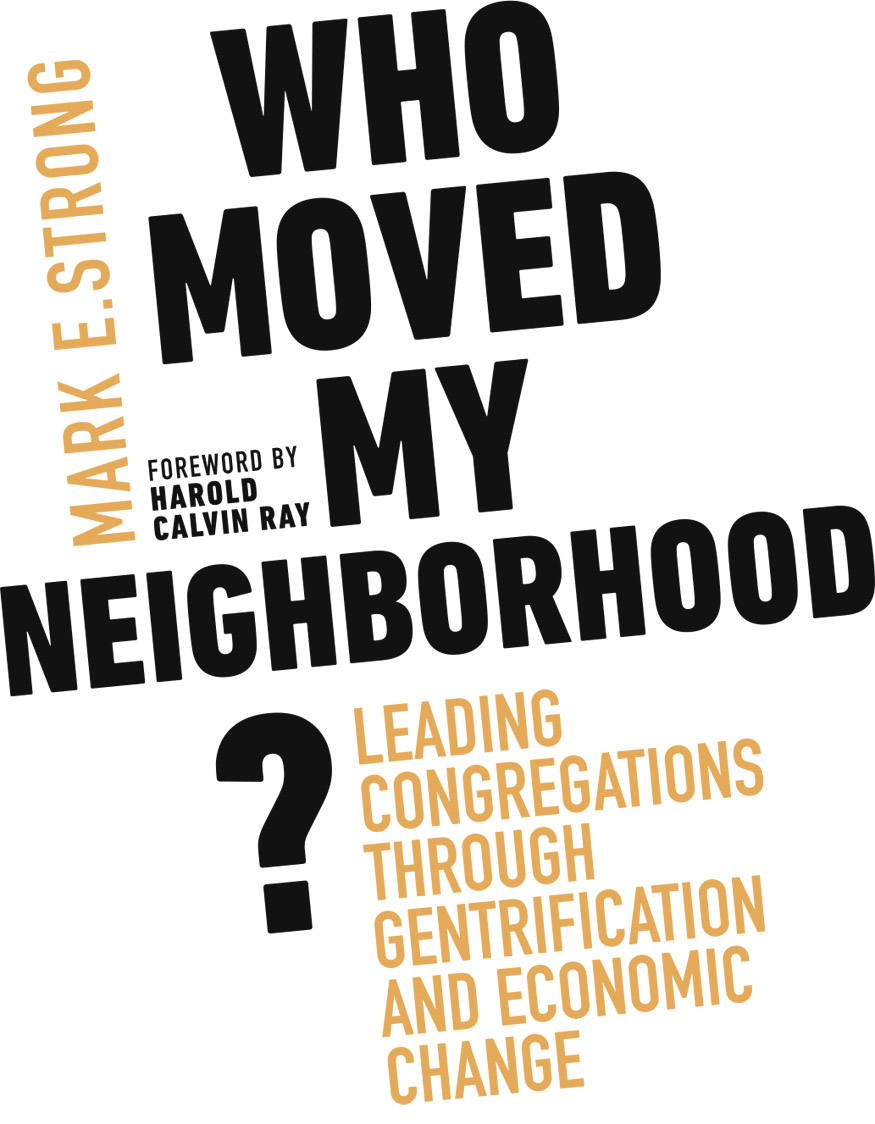

2022 by Mark E. Strong

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Press is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges, and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, visit intervarsity.org.

Scripture taken from the New King James Version. Copyright 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

While any stories in this book are true, some names and identifying information may have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Published in association with Jenni Burke of Illuminate Literary Agency: www.illuminateliterary.com.

The publisher cannot verify the accuracy or functionality of website URLs used in this book beyond the date of publication.

Cover design and image composite: David Fassett

Images: steps of a scaffold: acilo / iStock / Getty Images

prairie church: Joanna McCarthy / The Image Bank / Getty Images

colorful, ripped grunge paper: NikolaVukojevic / iStock / Getty Images

black and white grunge paper: NikolaVukojevic / iStock / Getty Images

historic brick wall: omersukrugoksu / E+ / Getty Images

construction crane: ROBOTOK / iStock / Getty Images

rough textured pearl white paper: tomograf / E+ / Getty Images

ISBN 978-1-5140-0239-1 (digital)

ISBN 978-1-5140-0238-4 (print)

This digital document has been produced by Nord Compo.

This book is affectionately dedicated to the

Life Change Church family

for your resiliency, determination, and faith

in the Lord Jesus Christ,

for your faithfulness in continuing to be the church

even though the neighborhood around you has moved.

And to the many churches

that find themselves in a different neighborhood

though they have not moved.

Foreword

Harold Calvin Ray

E very once and again, there arises from the midst of the rancorous clamor and passionate outcry of those who protest against recognized but curable social injustices and economic inequities a distinctive voice speaking with clarity, precision, and pragmatism in an effort to assuage the repetitive rehearsals of the obvious by presenting effective, solution-oriented alternatives to those wrestling with the issues at hand. Escaping for the moment the hearty temptation to prolong the exercise of bemoaning and lamenting, this voice chooses to light a candle of hope even while cursing the darkness of the communal despair.

Writing with remarkable and deliberate transparency, buttressed by his experiential credibility, Dr. Mark Strong in his timely and prophetic work Who Moved My Neighborhood? presents his foot soldier contemporaries in pastoral ministry with a revelatory self-help manual. This powerful treatise promotes and expedites a healing and reconciliation process for those pastors who find themselves facing the conundrum of anger, fear, and frustration. These emotional extremes are the understandable result of pastors being encumbered with the indelible challenge of leading what remains of a dispersed congregation into meaningful engagement with a neighborhood that they no longer recognize.

A 2020 national report titled Never More Urgent: A Preliminary Review of How the U.S. is leaving Black, Hispanic and Indigenous Communities Behind from the National Center for Faith-Based Initiatives noted that the identification and elimination of the policies, practices, and preferences that have historically, socially, and economically disenfranchised communities of color were a foremost but essential challenge of our modern-day society. This, of course, indicates that we are seriously interested in affirmatively addressing the glaring disparity across all spectrums of quality of life indices created by those policies, practices, and preferences.

The report further noted that the irrefutable disproportionate effect of Covid-19 on communities of color, when superimposed on already existing policy disparities, further demonstrated the dramatic quality of life gap experienced by minority communities. As such, the pandemic essentially served as a floodlight illuminating a myriad of debilitating maladies strangling the sustainable development of Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities.

However, while the Covid-19 pandemic rightfully focused media and governmental attention on the impact felt across all sectors of community life, another more historically rooted malady that dramatically and adversely affects the longevity, vitality, and sustainability of communities continues to run its course through the veins of communities of color in many of our nations largest cities. Gentrification serves to disrupt community life as it had been known and displaces a communitys commonwealth of historically rooted family trees, which had been responsible for fomenting dynamic, entrepreneurial, and front porchoriented community life.

It is clear that gentrification in and of itself need not necessarily be a bad thing. Every community needs change and must change as we encounter the white water rapids of cultural and societal change, as well as technological connectivity in our world. That stated, gentrification is only a good thing when the resulting evolution of the community does not simultaneously and inherently mean the elimination of that community!

Inner city development with such avarice and malevolent intent critically devalues the community that was with a presumptive and tragically flawed conclusion that the historic and passionate stakeholders of that community need not be consulted in the redesign nor included in the economic benefits and entrepreneurial opportunities resulting from that redesign. As Jane Jacobs warned nearly sixty years ago in her work titled The Death and Life of Great American Cities, such a flood of investment capital into reshaping historical neighborhoods according to the whims of outside forces is no constructive way to nurture cities.

Daniel Herriges, senior editor of Strong Towns, aptly notes that unfortunately concentrated poverty and its mirror image, concentrated affluence, are at historic highs. And our neighborhoods are caught between a destructive pair of outcomes: either experience stagnation and slow decay, or a cascade of redevelopment that leaves a place scoured of its former identity. He continues, We need to retool our regulatory processes and financing systems to legalize small. Right now, convoluted zoning and development rules, long and uncertain approval processes, and financing mechanisms that favor predictability and standardization have left an oligopoly of deep pocketed developers as nearly the only ones who can afford to be in the game. This precludes many citizens from playing a meaningful role in co-creating the places they will live. And it is at the root of Americas overlapping housing and affordability crises.