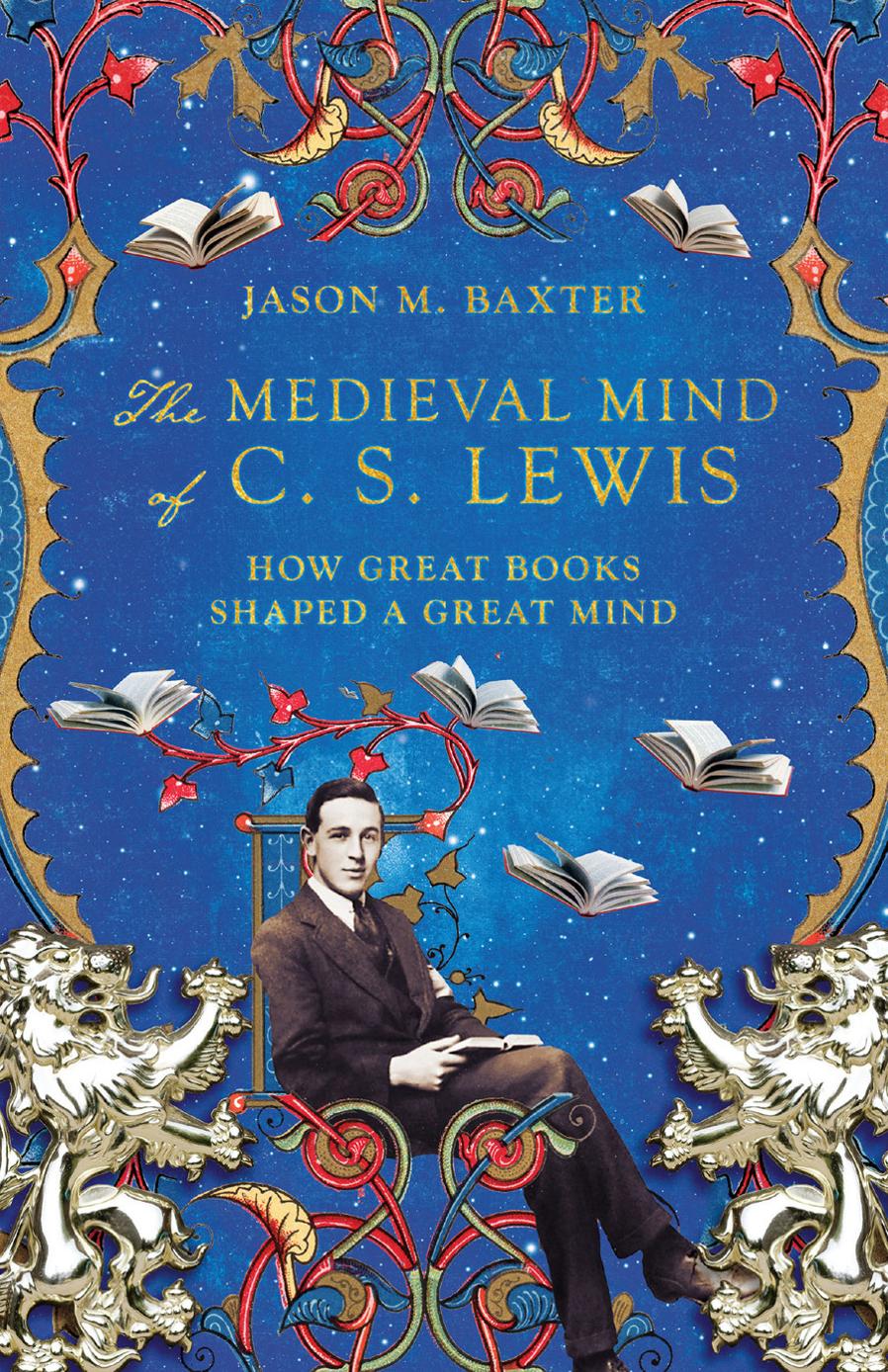

JASON M. BAXTER

THE MEDIEVAL MIND

OF C. S. LEWIS

HOW GREAT BOOKS

SHAPED A GREAT MIND

For my parents, Bob and Pauletta,

and my brother, Josh.

With immortal love.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I WOULD LIKE TO THANK MY FRIEND Jim Tonkowich for getting this whole project started through his invitation to teach a distance learning course at Wyoming Catholic College. My South Bend friends, Kirk and Maggie Doran, and Steve and Sue Judge, Colum Dever, and Matt Vale provided the original audience for half of this book. Special thanks to Michael Ward and Jahdiel Perez for the invitation to speak at the C. S. Lewis Society in Oxford, where I delivered an early version of the chapter on Lewis and science. Paul Prezzia invited me to St. Gregorys Academy, where I delivered a version of the introduction.

ABBREVIATIONS

| DI | C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature, Canto Classics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964). |

| EC | C. S. Lewis, Essay Collection and Other Short Pieces, edited by Lesley Walmsley (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2000). |

| Letters | C. S. Lewis, The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper, 3 vols. (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 20052009). Vol. 1: Family Letters: 19051931; vol. 2: Books, Broadcasts, and the War: 19311949; vol. 3: Narnia, Cambridge, and Joy: 19501963. Individual volumes are cited by volume number only. |

| SBJ | C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1955). |

INTRODUCTION

THE LAST DINOSAUR AND THE SURPRISING MODERNITY OF THE MIDDLE AGES

It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in-between.

C. S. LEWIS, ON THE READING OF OLD BOOKS, EC, 439

IN THE EARLY 1960s, the editors of the Christian Century sent a question to one hundred of the most famous literary and intellectual personalities of the day: What books did most to shape your vocational attitude and your philosophy of life? The editors were trying to map the books that had shaped the minds of their generation. C. S. Lewis was among those polled.

By that time, Lewis had already been famous for two decades, as a novelist, essayist, theologian, as the Christian Century summed him up, curiously leaving out something he considered essential to his intellectual identity. He was particularly admired for his Screwtape Letters, his war-years broadcast, Mere Christianity, and for his imaginative, fictional writings (especially The Chronicles of Narnia, published throughout the 1950s). Already in September 1947, he had been on the cover of Time magazine, whose feature article on him was tellingly titled, Don vs. Devil. And over those years, he had spent two hours a day patiently responding to the letters that poured in from his devoted admirers from across the Anglophone world. He had hosted journalists seeking interviews with him and had accepted dozens of invitations to give lectures and sermons. In sum, his cultural standing was founded on his perceived mastery of psychology, his ability to recast Christianity imaginatively in myth, and for his work in apologetics. As Rowan Williams, summing up fifty years of admiration, put it, Lewiss gift was what you might call pastoral theology: as an interpreter of peoples moral and spiritual crises; as somebody who is a brilliant diagnostician of self-deception.

THE THIRD LEWIS

But there was, as his friend Owen Barfield once said, a third Lewis. In addition to the Christian apologist, whose sagacious words delivered over radio waves had been so comforting during Englands darkest hour, and in addition to Lewis the mythmaker, the creator of Narnia and fantastic tales of space travel, there was Lewis the scholar, the Oxford (and later Cambridge) don who spent his days lecturing to students on medieval cosmology and his nights looking up old words in dictionaries. This Lewis, as Louis Markos puts it, was far more a man of the medieval age than he was of our own. This was the man who read fourteenth-century medieval texts for his spiritual reading, carefully annotating them with pencil; who summed himself up as chiefly a medievalist; the philologist, who wrote essays on semantics, metaphors, etymologies, and textual reception; the distinguished Oxford don and literary critic who packed lecture theatres with his unscripted reflections on English literature; the schoolmaster who fussed at students for not looking up treacherous words in their lexicons; the polyglot pedant who did not translate his quotations from medieval French, German, Italian, or ancient Latin and Greek in his scholarly books; the man who wrote letters to children recommending that they study Latin until they reached the point they could read it fluently without a dictionary; the critic who, single-handedly, saved bizarre, lengthy, untranslated ancient books from obscurity. Before he was famous as a Christian and writer of fantasy, he was famous among his students for his academic lectures, which bore such scintillating titles as Prolegomena to Medieval Literature and Prolegomena to Renaissance Literature. Long before he ever thought of defending Christianity, he dedicated himself to defending the beauty and wisdom of the premodern literature of Europe. It was this professorial Lewis who in a 1955 letter lamented that modern renderings of old poems made up a dark conspiracy... to convince the modern barbarian that the poetry of the past was, in its own day, just as mean, colloquial, and ugly as our own. This was Lewis the antiquarian, who devoted muchindeed, mostof his life to breathing in the thoughts and feelings of distant ages, and reconstructing them in his teaching and writing. We find him recommending to general audiences that they read one old book for every modern one (as in the epigraph), and advising those seeking spiritual advice to old books: I expect Ive mentioned them before: e.g. The Imitation, Hiltons Scale of Perfection,... Theologica Germanica... Lady Julian, Revelations of Divine Love. Likewise, we hear him confess, in a 1958 letter to Corbin Scott Carnell that he could hardly think of any debt he owed to modern theologians. He thought Carnell had paid him a wholly undeserved compliment, assuming his reading was greater than it was. There are hardly any such debts at all.... Christendom, you see, reached me at first almost through books I took up not because they were Christian, but because they were famous as literature. Hence Dante, Spenser, Milton, the poems of George Herbert... were incomparably more important than any professed theologians. Later, once he had been caught by truth in places where I sought only pleasurecame St. Augustine, Hooker, Traherne, Wm Law, The Imitation, the Theologia Germanica. As for moderns, Tillich and Brunner, I dont know [them] at all. In sum, this was C. S. Lewis the medievalist.

Even for the editors of Christian Century, who summed up Lewis as a novelist, essayist, and theologian, it was easy to forget that the man who had become a celebrity Christian had an ardent love for studying the technical features of medieval language (indeed, sound laws that regulate vowel changes!), manuscript transmission, old books of science, and medieval poetic form. To many of Lewiss readers, it might seem absurd, maybe even irresponsible and escapist, to devote the whole of ones adult life to the study of dead languages (Anglo-Saxon, Old Norse, Provencal, medieval Italian, or Latin) or reconstructing the details of ancient bestiaries (allegorical readings on the spiritual meaning of animals). Sure, studying New Testament Greek is useful, but trying to understand the subtleties of medieval debates, say, on the exact nature of moon spots (as Dante does in Paradiso 2)? But Lewis, of course, did do exactly that: he devoted the entirety of his adult life to precisely these kinds of academic pursuits. But perhaps of even greater surprise is the fact that these scholarly pursuits were not separate from his personal life. Lewis did not stop thinking about medieval symbolism, cosmology, and allegory when he left the office. Indeed, what is most telling is that even in the midst of the messy and painful affairs of life and grief and loss, his mind habitually returned to the old books for comfort and consolation. For instance, in an intimate letter to Sheldon Van Auken, after his friend had lost his wife, Lewiss mind could think of nothing better than to recommend his friend read Boethiuss Consolation of Philosophy in the Loeb edition, with Latin pages facing the English translation. He then followed up with the recommendation of a second medieval book: As you say in one of your postscriptsyour love for Jean must, in one sense, be killed and God must do it. Youd better read the Paradiso hadnt you? Note the moment at which Beatrice turns her eyes away from Dante to the eternal Fountain, and Dante is quite content. Only a few years later, in 1961, when Lewis was suffering from grief over the loss of his own wife, Joy, his mind drifted back to the same passage in Dante. The last line in A Grief Observed is the same he had quoted to Van Auken: I am at peace with God. She smiled, but not at me. Poi si torn alleterna fontana.