For Devon,

who has walked

beside me

on the Way

PREFACE

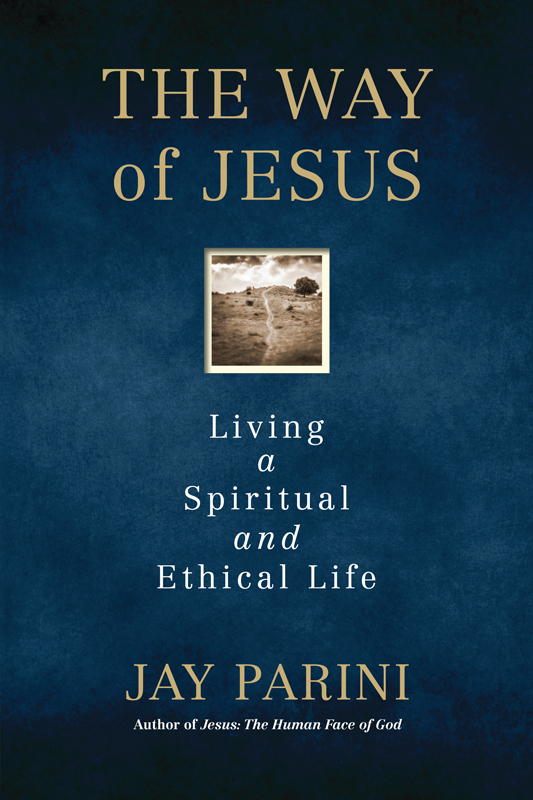

This book follows from an earlier one, Jesus: The Human Face of God (2013). There I looked briefly at the life of Christ, arguing that his story represents a kind of mythos, the Greek word for myth, which I defined not as a story that is untrue but as one that is especially true. What interested me were the symbolic contours of his life, his example of suffering and rebirth, and his remarkable teachings, which have been hugely influential. They have changed the lives of billions of people over two millennia, including my own.

In this study I examine what it means to follow the Way of Jesus, his path toward God, and his effort to seek out and create the Kingdom of God, as defined by himself and some of his most effective and influential interpreters, such as Paulthe great apostleand generations of writers and thinkers who have confronted his teachings and example, all of them attempting to put them into practice. I begin with a chapter on my own spiritual progress over the past six (nearly seven!) decades, a wandering path in and out of Christianity, during which times Ive embraced many versions of what it means to trust in God and follow the example of Jesus. In the subsequent chapters, I frequently allude to my own struggles and occasional successes, dealing frankly with my occasionally vexed relations with traditional ideas about salvation, which I prefer to call enlightenment, a better translation of the Greek term soteria.

In the second chapter, I examine the Christian mind, its complexities, and the problems that Christian thinking attempts to solve or understand. I take it for granted that most people these days, especially well-educated ones, have little time for supernatural religion or religious practices. I address some key philosophical issues frankly, stepping into the areas of epistemology and ontology: these, in turn, refer to the theory of knowledge and ideas about existence itself, and how we come to be who we are. As I must, I draw on a range of ancient and modern theologians, poets, and thinkers, quoting freely throughout. My own thinking operates within a web of textuality, and I try to acknowledge that freely, as a way of marking my own debts but also as a way of directing readers to other useful texts. In this chapter I look closely at the biblical tradition, including the Hebrew and Greek scriptures, and point in other directions as well, including the Gnostic Gospels. In other parts, I confront various matters of concern to Christians, including the stumbling blocks of miracles (and the supernatural) and human suffering. This chapter ends with a reading of the Resurrection as something more than simple resuscitation. Its about ongoing change, the daily rebirth and renewal of the spirit.

In the third chapter I turn to the nitty-gritty of Christian practice, as represented by the Church Year. Christians have been given a huge gift, the cycle of the seasons, with liturgical markers throughout. Christmas and Easter are simply the high points of this complex cycle. The calendar works to further our trust in God, to deepen our sense of what it means to follow the Way of Jesus. It also serves to bring the faith community into focus, into reality. Public prayer and confession and Holy Communion remain vital aspects of any Christian life, and I do my best to outline the course of this unfolding calendar, with its unique liturgies and language, its profusion of symbols, its manner of lifting us over and through the days of the year as we follow in the steps of Jesus.

In the final main chapter, I use T. S. Eliots classic collection of poems Four Quartets as a guide to Christian living. These four poems, which are in each case a sequence of connected poems, draw heavily on the language of Christianity while bringing into play insights from Hinduism and Buddhism as well. Eliot was a remarkable man, and his profound thinking about the work of the spirit in the life of the active mind is for me exemplary, infinitely suggestive. In the third sequence, The Dry Salvages, Eliot marks out five key things for Christians to consider as they follow the Way of Jesus: Prayer, observance, discipline, thought, and action. I consider each of these in turn, with personal reflections on their importance as signposts along the Way. Eliots sense of eternity as here, now, always strikes me as a perfect description of salvation. His approach, in its modesty and profundity, remains part of my life, and I reread this sequence of poems often.

This isnt a work of evangelism. Its an attempt to understand what Jesus really meant, his effort to put love first and foremost in our daily lives, and to describe my own efforts to follow his example. My hope is that this book will prove helpful to others who struggle, as I do, with some of the basic questions about human existence: its limits and sadness, its possibilities for awareness and understanding, its undeniable glories, believing firmly that in Jesus, all things are possible (Mark 10:27).

ONE

JOURNEYING BY FAITH

The eye is the first circle; the horizon which it forms is the second; and throughout nature this primary figure is repeated without end. It is the highest emblem in the cipher of the world. Saint Augustine described the nature of God as a circle whose center was everywhere, and its circumference nowhere. We are all our lifetime reading the copious sense of this first of forms.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Circles

I often think of my own faith journeyor journeysas a zigzag path over many decades, with numerous periods of drought, stretches of complete indifference and alienation from God, when I felt the brown cracked earth under my feet. The journey was never easy, and it remains just as tortuous after many decades, although it helps to have some experience with spiritual trekking itself. Of course, there were exhilarating times at every point, oases of connection, with a sense of being part and parcel of a larger spirit that holds me, and everyone, in loving embrace. These are the times Saint Paul refers to in 1 Corinthians 15:28, occasions when we sink into the experience of unity with God (atonement) deeply and completely, until God becomes all in all. This is salvation, that healing motion of the soul, and the destination we seek.

I remember so vividly reading in Emersons journals as a young man. He wrote that the highest revelation is that God is in every man, and I underlined this passage several times, with exclamation marks in the margins. Yes, I thought: God is here, inside me, inside everyone. He is the center of the endless circles we trace throughout our lives. Only recently, in fact, a friend asked me where I thought God was, and I touched the coffee table before us, and I said, In this wood. And it seemed astonishingly true.

I wish I could say that the times of connection or atonement (meaning at-one-ment with God), with their exhilaration and peace, were common occurrences in my life. But they remain moments in and out of time, experienced less often in church or periods of focused devotion than on country roads in late summer, in the leafy woods near my house, sitting by a pond, reading in bed, or writing in a caf. Quite often they have been found in conversations with my wife, who has followed her own intense path toward God, often coinciding with mine, over nearly four decades. She and I have shared a great deal on so many levels.