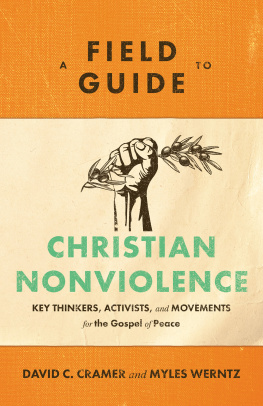

2022 by David C. Cramer and Myles Werntz

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meansfor example, electronic, photocopy, recordingwithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Baker Publishing Group publications use paper produced from sustainable forestry practices and post-consumer waste whenever possible.

Contents

Endorsements

Title Page

Dedication

Copyright Page

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Nonviolence of Christian Discipleship

Following Jesus in a World at War

2. Nonviolence as Christian Virtue

Becoming a Peaceable People

3. Nonviolence of Christian Mysticism

Uniting with the God of Peace

4. Apocalyptic Nonviolence

Exposing the Power of Death

5. Realist Nonviolence

Creating Just Peace in a Fallen World

6. Nonviolence as Political Practice

Bringing Nonviolence into the Public Square

7. Liberationist Nonviolence

Disrupting the Spiral of Violence

8. Christian Antiviolence

Resisting Sexual and Gender-Based Violence

Conclusion

Bibliography

Index

Back Cover

Preface

T his little book is two decades in the making. On September 11, 2001, the two of us were just a couple weeks into the fall semester of our respective academic programsDavid as a freshman Bible and philosophy major in Indiana and Myles as a second-year seminarian in Texas. As young, white evangelicals, neither of us had thought deeply about the relationship between violence and our Christian faith. With the collapse of the World Trade Center towers came the collapse of our innocence.

We were sent back to Scripture with new questions and new lenses. Jesuss Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 57) took on a new sense of urgency. When Jesus said to love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you (5:44), did he have in mind those who are intent on killing you? And when he said not to resist an evildoer (5:39), did that entail refusing to engage in violence for personal or national defense? Such questions sent us searching for answers, not only in Scripture but also in Christian theology and ethics.

As with many evangelicals looking for answers to questions about violence and the Christian faith, we were directed to the

In the meantime, a number of survivor advocates were working to bring to light the long history of Yoders sexual violence toward womena history that for decades had been minimized or conveniently overlooked by male scholars like us who were drawn to Yoders arguments for Christian nonviolence. In 2013, Mennonite mental health clinician and pastoral theologian Ruth Krall published a collection of essays providing an in-depth case study of Yoders sexual violence and the Mennonite Churchs response. That same year, Mennonite theater professor, survivor, and survivor advocate Barbra Graber wrote an essay titled Whats to Be Done about John Howard Yoder? which struck a nerve in the Mennonite world and beyond. An avalanche of testimonies of and responses to Yoders sexual violence ensued, and once again, our innocencethis time about our own complicity in propagating the work of a known sexual predatorcollapsed.

The revelations about Yoder caused us to scrutinize the foundations of our commitments to Christian nonviolence. If one of the leading twentieth-century voices for Christian nonviolence was himself violent in such heinous ways, is Christian nonviolence itself a sham?

Instead of leading us to reject our commitments to Christian nonviolence, this time of questioning and scrutinizing led us to broaden our understanding of nonviolence and deepen our commitments to iteven as our convictions were transformed in light of what we learned. We found that Yoders own approach to nonviolence has precedents in figures like Andr and Magda Trocm, who were inspired by Jesuss revolutionary nonviolence to nonviolently resist the Nazis and the Vichy government by harboring thousands of Jewish refugees in the small French town where Andr pastored. Moreover, we came to see Christian nonviolence not as a unified, coherent position but as a dynamic, multivalent tradition that includes a number of identifiable streamsnot all of which are entirely compatible with one another. We came to see that this multifaceted tradition includes mystics and liberationists, socialists and anarchists, Catholics and Methodists, in addition to Mennonites focused on discipleship.

Yet in our conversations about Christian nonviolence with othersboth those committed to Christian nonviolence and those opposed to itwe often heard it described in a fairly limited way as nonviolence of Christian discipleship. This is the view that Christians practice nonviolence because Jesus taught us to and exemplified it in his own life, which serves as a model for Christian disciples. It is also the view that Yoder both popularized and provided scholarly credibility to through his many writings but especially his 1972 work, The Politics of Jesus . Even now, when we self-identify as Christian pacifists or advocates of Christian nonviolence, we often find ourselves pigeonholed as Yoderians and our view described as the Yoder-Hauerwas position, which combines Yoders approach with that of his friend and colleague Stanley Hauerwasanother prominent pacifist of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.