Published by BYU Studies in conjunction with Utah State University Department of Religious Studies and the Academy for Temple Studies, https://www.templestudies.org.

Copyright 2013 Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

Opinions expressed in this publication are the opinions of the authors, and their views should not necessarily be attributed to the Academy for Temple Studies, Utah State University, BYU Studies, Brigham Young University, or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, digital, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in an information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. To contact BYU Studies, write to 1063 JFSB, Provo, Utah 84602, or visit http://byustudies.byu.edu.

Contents

Gary N. Anderson, Philip L. Barlow, and John W. Welch

Margaret Barker

Laurence Paul Hemming

John W. Welch

Daniel C. Peterson

LeGrande Davies

John L. Fowles

About This Publication

This volume contains the presentations given at the first conference of the Academy for Temple Studies, co-sponsored by the Department of Religious Studies at Utah State University in Logan, Utah, on October 29, 2012. The underlying papers and transcripts of presentations and panel discussions were edited and prepared on behalf of the Academy for Temple Studies by Jennifer Hurlbut, Marny K. Parkin, and other staff of BYU Studies at Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

The contents are conference presentations and most should be considered as preliminary reports of works in progress. We present them as a record of this conference, for the edification of readers who wish to know about current efforts in the field, and to stimulate further research and discussion. Temple studies as an academic discipline is a fairly young field. Some of the ideas explored and presented at this conference have not yet undergone peer review or full source checking.

The Academy for Temple Studies was formed in 2012 by a group of American scholars and interested supporters who came together as a result of their participation in the Temple Studies Group in London. They invited Dr. Margaret Barker and Rev. Dr. Laurence Hemming of the London group to present at this first conference in North America. The London Temple Studies Group promotes and enables study of the Temple in Jerusalem, believing that the world view, traditions, customs and symbolism of the Temple were formative influences on the development of Christianity. More information about its objectives and symposia can be found at the website templestudiesgroup.com.

The website of the Academy for Temple Studies is www.templestudies.org. On this site one can find videos of the 2012 Logan conference presentations as well as suggested readings and a growing bibliography of temple studies publications. We are grateful to the many people whose assistance, support, and attendance have made all of this possible. We hope this website will be of great use to those interested in all aspects of ancient and modern temples around the world.

Gary N. Anderson

Philip L. Barlow

John W. Welch

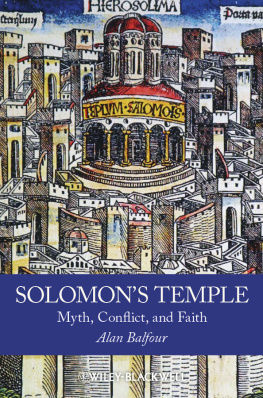

Restoring Solomons Temple

Margaret Barker

The Christians saw themselves as restoring Solomons temple, and Christian theology grew rapidly around this fundamental claim. Some forty years ago, when dealing with the formation of the first Christian teaching, Martin Hengel wrote, One is tempted to say that more happened in this period of less than two decades than in the whole of the next seven centuries, up to the time when the doctrine of the early church was completed. He was writing about the title son of God, which was a part of temple teaching (Psalm 2:7), but his observation applies to temple theology as a whole: How did the first Christians know so much, so soon?

There is an ambiguous attitude towards the temple in the New Testament: Jesus drove the traders out of the temple, declaring that the house of prayer had become a den of robbers (Matthew 21:1213; Mark 11:1517; Luke 19:4546; John 2:1416). He told parables that condemned the temple authorities: they were the wicked and greedy tenants of the LORDs vineyard who would be punished (Matthew 21:3341; Mark 12:19; Luke 20:916). He prophesied that the temple would be utterly destroyed (Matthew 24:12; Mark 13:12; Luke 21:56). The whole of the Book of Revelation is about the destruction of the temple, preceded by the opening of the seven seals of the little book, the seven trumpets, and then the seven vessels of Gods wrath tipped upon Jerusalem (Revelation 56; 811; 16). Despite this, Peter taught newly baptized Christians that they were living stones in a spiritual temple, a royal priesthood, Gods own people called from darkness into light (1 Peter 2:410); and the unknown writer of the book of Hebrews used temple symbolism to explain the meaning of Jesuss death (Hebrews 9:114).

The explanation for these two very different attitudes lies over six centuries before the time of Jesus, but the results of events so long ago were still important. From the end of the eighth century BCE, the time of the prophets Hosea and Isaiah, there had been pressures building in Jerusalem to change the ways of the temple and to give greater prominence to Moses, rather than to the king, and these pressures finally triumphed in the time of King Josiah a century later. There are two accounts of this period in the history of Jerusalem:

The biblical one in 2 Kings 24:14 says that Jerusalem had been under the rule of wicked kings who did not observe the law of Moses as set out in Deuteronomy, and because of their evil ways, the temple was destroyed and the people were scattered;

The nonbiblical one in 1 Enoch 93:9 says that this was a period when the temple priests lost their spiritual vision and abandoned Wisdom, and so the temple was burned and the people were scattered.

Thus the writer of 2 Kings saw the changes as good, and the writer of 1 Enoch saw them as a disaster. Since 2 Kings is in the Bible and 1 Enoch is not, this has coloured most reconstructions of the events.

The crisis came in the reign of King Josiah, who supported the pro-Moses group and in 623 BCE began a series of violent purges to rid his kingdom of the older ways, which he regarded as impure (2 Kings 2223). He removed many of the ancient furnishings from the temple because they symbolised certain teachings which he would no longer allow: in particular, he removed all traces of a female figure, represented by a great tree, which he burned by the sacred spring and had its ashes beaten to dust and scattered. We should probably recognise this tree as a great menorah. Then he purged his kingdom, destroying all the hilltop places of worship out in the countryside, the sacred trees and the pillars. Many of the priests of these places were driven out. Finally, Josiah celebrated a great Passover, the major feast of the pro-Moses party.

Then came the disaster. The Babylonians invaded Josiahs kingdom: they came first in 597 BCE, took away all the temple gold and removed the ruling class into exile. They appointed a puppet ruler, but he proved unreliable, and so they returned and destroyed Jerusalem in 586 BCE. They burned the temple and the city, and took more people into exile. Others fled as refugees to Egypt (2 Kings 2425). Such a catastrophe was long remembered, and other significant details can be found in Jewish writings as much as nine centuries later. These details shed a very different light on Josiah and his cultural revolution. Many people deserted Jerusalem and went to join the invading Babylonians. Jeremiah says that King Zedekiah was afraid of these people (Jeremiah 38:19), and the Jerusalem Talmud, compiled about 400 CE, tells us where they went. It has a cryptic reference to 80,000 young priests who fought with the Babylonians against Jerusalem, presumably to regain their position after Josiah had driven them out. These young priests later settled in Arabia.