THE

John Michell

READER

In this interesting collection, full of memorable details, JohnMichell commits many charming acts of political heresy againstthe received wisdoms of contemporary life, advocating by examplewhere freedom still resides.

RICHARD HEATH, AUTHOR OF SACRED NUMBER AND THE LORDS OF TIME

Joscelyn Godwin has shown exceptional empathy with Michellsworldview in his judicious arrangement of the writings.

PATRICK HARPUR, AUTHOR OF THE SECRET TRADITION OF THE SOUL AND THE PHILOSOPHERS SECRET FIRE

Refreshingly original, yet genuinely grounded in tradition. JohnMichell is wise, mischievous, and amusing. He has expanded thefrontiers of British sanity and enriches the lives of those who knowhim and his works.

RUPERT SHELDRAKE, AUTHOR OF MORPHIC RESONANCE

Forget trepanning, John Michell opened my third eye years ago.His revelations and the mysteries he touches upon are in my headforeverlife would be dead dull and probably impossible withoutthis extra and true dimension.

CANDIDA LYCETT GREEN, COAUTHOR OF THE GARDEN AT HIGHGROVE

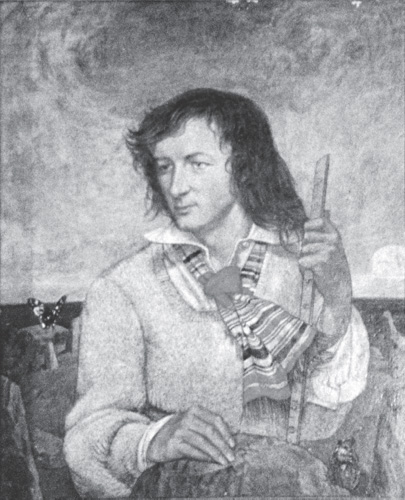

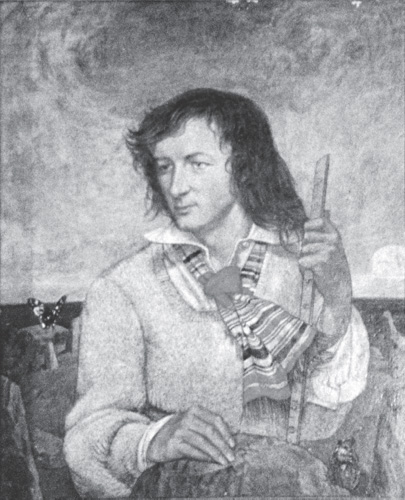

The Geometer No. 2.

Tempera painting of John Michell by Maxwell Armfield, ca. 1972.

INTRODUCTION

A Prophetic Vision

By Joscelyn Godwin

I n the dying years of the second millennium one of the few things that gave pleasure to this expatriate Englishman, when he let his minds eye wander to what was left of his native land, was the thought that in an upper room somewhere in Notting Hill sat John Michell, writing another book, painting geometric figures, sharing a midnight feast with his visitors, or turning out another feuilleton for The Oldie.

It is not too much to say that John Michell was a prophet. Prophets do not foretell the future so much as warn what may come to pass if events continue on their present course. Nowadays this is so blindingly obvious that we hardly need prophets to tell it to us. But there is a rarer prophetic gift, which is the seeing of forms in what Plato called the World of Ideasnot the imaginary ideas of men and women, but the divine or daemonic ideas after which the material world is formed. Ezekiel saw the Chariot of the Most High; John the Divine saw the New Jerusalem; Mohammed in his night-journey passed through the planetary spheres and met the other prophets of his lineage. Such visions may be warnings too, but they also inspire confidence in the meaning and goodness of the cosmos; they enable us to imagine Paradise here and now and to adjust our lives in harmony with it.

Since his publication of the New Jerusalem canon in 1971, a prophetic vision of the latter kind was the foundation of all of John Michells writings, and his efforts were bent on bringing about its new descent as a source of joy, sanity, and sacred order in the world. These little essays were like the foam thrown off by the great wave of creative energy set in motion by this discovery, which Michell characterised, in all humility, as a revelation.

John Michells other role was that of a guardian of tradition and its defender against the new men who mistrust everything ancient, beautiful, or suspect of elitism. These tinpot emperors come in for a sound chastisement in these pages, and it is not sheer malice to enjoy hearing someone shout that they are stark naked. The tradition that Michell defended has always been elitist, but not in the sense of favoring birth, money, or even brains. Instead, it fostered the quality, in every sphere, of being truly and comfortably what one is. In this sense, those who live by cultivating the land or by the careful work of their hands are more deserving of respect than media stars (even royal ones) or socialites. Moreover, Michell had a particular empathy for those at the bottom of the ladder who might have found their place in a more traditional social order but whom present-day conditions have made outsiders. He liked those who maintained their dignity and refused to compromise their own nature: tramps, canal folk, and New Age travellers, or the West Africans and Asians of his London district.

In such an age gentle mockery is a better weapon than fulminating rants against the wrongness of things. Michell was gentle, though he knew where to stick the pin for maximum effect. He was a humoristthe kind who did not try to be funny, but simply was so because he saw things from angles that were unexpected and sometimes forbidden. Americans obviously value British humor for this last quality, living as they do under a rule of euphemism that would never, for example, call a magazine for senior citizens The Oldie.

Among the forbidden categories are those censored not out of moralism or sensitivity but because they are beyond the understanding, hence beneath the notice, of the experts. One example is calling into question William Shakespeares authorship of the plays ascribed to him, to which Michell dedicated his longest book, Who Wrote Shakespeare? Alas, a plan for an exhibition on the subject in Stratford-upon-Avon proved unequal to the vested interests of the tourist industry. Long before that, Michell was a thorn in the side of the prehistoric archaeologists because he asked the wrong sort of questions and produced the wrong sort of evidence, while getting people much more excited about prehistoric remains than the experts ever could. If he was right, and there was a worldwide culture of high mathematical and technical achievement in the Stone Age, history books will have to be rewritten. But to give these experts their due, the trend of revision in prehistory has turned in Michells favor, and the seeds planted in the popular mind by his early books flowered as the enthusiasts of the 1960s became the professors of the 1990s.

Moving from the past to the present, Michell was also an authority on things beyond the pale of respectability, New Age travellers of the intellectual world like flying saucers, crop circles, and weird phenomena that defy rational explanation. In his case, being an authority did not imply having the clue or the key to these, nor even believing that an explanation of them was possible. Such an admission is truly aggravating to the expert mind but no surprise to those who share Michells esteem for Americas great philosopher Charles Fort, who was content to say Lo! and unleash a flood of damned and inconvenient facts. The book Phenomena, written together with Robert Rickard and celebrating a long collaboration on the Fortean Times, collects instances of Teleportation, Stigmata, Fairies, Spontaneous Human Combustion, Falls of Liquids, and Mysterious Oozings, and so on, but without theories or explanations. This is of course the stuff of tabloids and urban legends, but when a serious and educated mind grapples with the evidence, the metaphysical consequences are quite momentous.

For all that he was a Platonist and a traditionalist, deeply enamored of a past that mirrored the divine order, Michell was also a radical of a typically English stamp. He belonged with William Blake, William Cobbett, William Morris, Henry W. Massingham, and those other defenders of Albion against its betrayers. Albion stands for the soul of Britain, which, like every race and nation, has its own potential perfection that enables it to sing its own melody in the chorus of humanity. It is no solution to the present cacophony to try to make them all mouth the same tune, whether composed in Washington or Brussels. But since the Reformationso goes the storythe giant Albion has been in bondage and decay. His sickness is too old and too deep to be curable by mere conservatism or political action; only a radical, even a surgical cure will serve, one that people can support from the depth of their souls, not their pocketbooks.

Next page