To Hooch

M Y THANKS GO to Stefan Dickers and all at the Bishopsgate Institute for literally pulling the archives to pieces in order to find an image or article for my research. Thanks for indulging all my weird requests and helping with all my Im just looking for queries. It has been a challenge but it has also been great fun. I would also like to thank all the team at The History Press for their help and support in creating this book. My thanks also go to the Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives for their continuing support. There are many others in the Tower Hamlets area who have supported me along the way and I hope this continues. Lastly, but most importantly, I would like to thank Hooch and Brown Owl for making this all possible. I have expanded my knowledge on this voyage of discovery and hopefully I will only dock for a while before setting off on the next adventure! As the Stepney motto says: A magnis ad maiora (from great things to greater)!

CONTENTS

BC

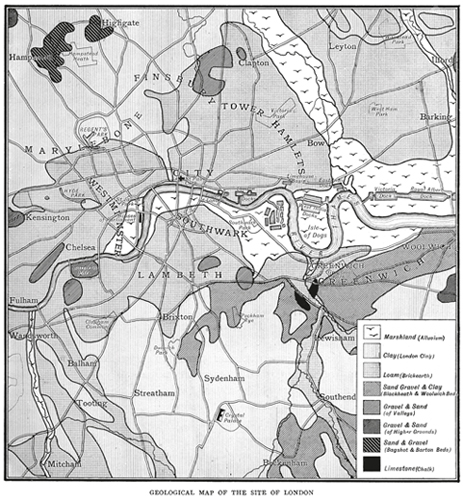

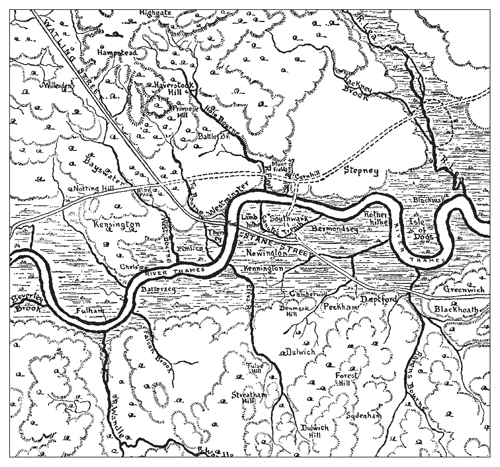

I N THE BEGINNING , the East End would have been a dark and forbidding place. In fact the area would have been a bog. The Thames was a tributary of the Rhine less than a million years ago, and the North Sea was the Rhine basin. With Hampstead in the north on high ground and Dulwich on the south, the Thames formed lagoons and marshes that were surrounded by the forest that covered all of the land.

Living creatures, men and animals, must have crossed into England by the neck of land connecting Britain with Europe, but by the time we first learn of them the sea had broken through the Straits of Dover and Britain was an island. At this time it was a good deal colder, so there were hairy mammoths and woolly rhinoceros, boars, bears, wolves, wild oxen, and sabre-toothed tigers. These animals roamed the forests and hunted each other, eventually becoming extinct. For man, the East End would have been suited to cultivation with farm implements fashioned by Stone Age man. It would have been a difficult and perilous time for the East Ender, but man survived.

With a lot of forest came a lot of rain, and the consequence was that the Thames had many tributaries to carry the water down from the north. Two are of note, the Lea, Londons defence on the east from time immemorial, and the Wallbrook. On the left bank of the Wallbrook, on a dry hillock near Cannon Street station, the first permanent settlement was made, at about the beginning of the Christian era. The Celts who built it probably called it Llyn-dim the lake-fort London. It was pretty safe from invasion, as it was 50 miles from the sea, but trade could flow up and down the river by boat.

The Celtic Britons were part of the territory of the Catuvellauni, the main group of the Belgic tribes who had invaded Britain in the second century BC . By the time Julius Caesar came in 55 BC and 54 BC , the Home Counties had become the Celts stronghold in Britain. The Celts were fierce and undisciplined and prone to fighting amongst themselves. They were warriors who were tall, fair-skinned with red or yellow hair, and fond of bright clothes and ornament. They were energetic, musical, and idealistic. They were also daring and clever seamen who traded with the Continent. Ratcliff (the red cliff) as the Saxons were to later name it, was, for the Celts, a convenient landing place nearby. Ever since, the East End has had a close maritime link with the mother-city.

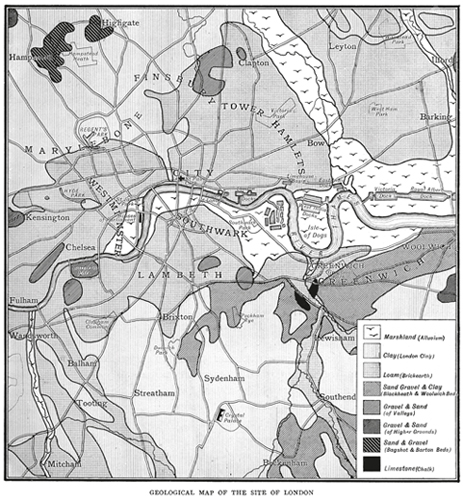

Geological map of early London. (Courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute)

AD 43

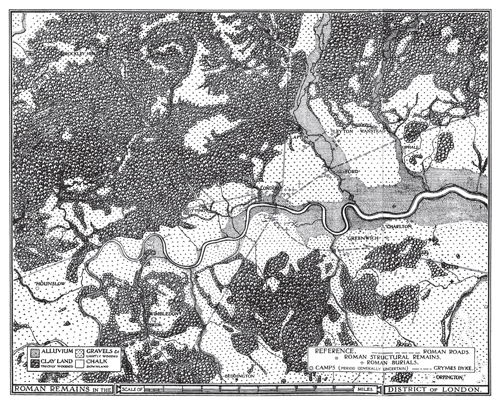

N INETY YEARS AFTER Julius Caesar called off his invasion of Britain, Emperor Claudius began the real occupation of Britain by the Romans. In AD 43 Claudius marched with his legions and his elephants down the British trackway to Old Ford and crossed the Lea to capture Colchester. Within the space of twenty years all of southern England became Romes. Boudiccas defeat and death in AD 61 marked the end of Celtic power in the South of England and the Romans replaced Albion, the Celtic name for the area, with Britain. The term Great Britain was not invented for another 1,600 years, however, when James I joined the kingdoms of England and Scotland. The Romans also tried to change Londons name to Augusta but failed.

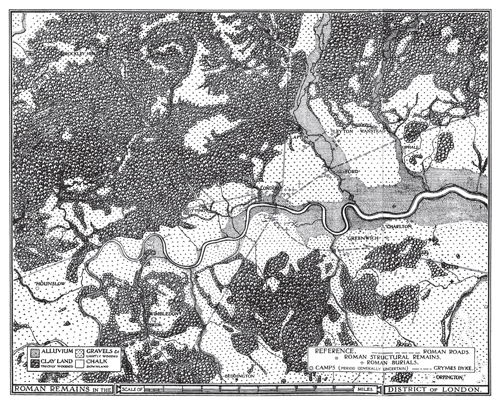

Physiographical map of the London district in Roman times. (Authors collection)

The Romans fortified London, which until then had been little more than a commercial port. They built their citadel on the other side of the Wallbrook and enclosed the ground from Cornhill to Thames Street and from Mincing Lane to the Wallbrook. They also built the first London Bridge. Their port was near the bridgehead and their market near the port, thus making Billingsgate the oldest London market. In the East End the Romans created orchards and gardens. Closer to the city, they buried their dead at Spitalfields and Ratcliff.

For 300 years Britain grew in wealth and importance. Roads were built. Notably the road following the line of Bethnal Green Road and Roman Road was built, joining the great port of Londinium to Colchester, the capital of Britain. Another Roman road went from the city wall along to Ratcliff, which may have been suitable as a landing place for ships. Just off the line of this road, at Shadwell, the remains were found of a Roman signal station. It is believed that the signal station would have been one of a series, designed to warn Londoners of impending enemy ships coming upriver from the sea.

When the Romans first conquered Britain they supressed the Druids, the priests of the Celts, but on the whole were tolerant of alien religions. In the fourth century, Emperor Constantine made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire, which appeared to challenge the Roman right to rule and had been persecuted previously under Roman law. Christianity never seems to have caught on very widely in Roman Britain. Less than 100 years after Constantines edict the Roman legions had left Britain and Christianity was nearly obliterated by the Saxon invasions that began in AD 445. Some 300 years of Roman peace had made the Britons civilised but soft, unable to effectively defend against the fierce heathen tribes from across the North Sea.

AD 450

T HE NAME STEPNEY comes from the Saxon Stebunhithe , meaning the landing place of Stebba or Stephen. During Saxon times most of the manor of Stepney was a rural rather than a maritime area, with marshlands in the south near the Thames and forests to the north, part of which is now Victoria Park. Considering the areas later development into maritime affairs, it is interesting that its original name is related to shipping.

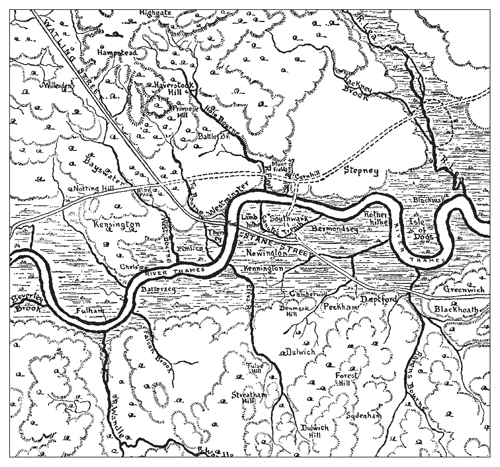

London before the houses. (Courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute)

It has been suggested that London may have been abandoned for some time, at least during the fifth century, due to Saxon invaders having little interest in urban life. Britain was divided up into kingdoms and East London became part of the kingdom of the East Saxons, which included present-day Essex, Middlesex and Hertfordshire. Later this domain was absorbed into the larger kingdom of Mercia.

Next page