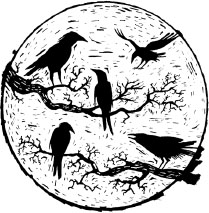

AN

UNKINDNESS

F

RAVENS

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2014

Illustrations copyright Aubrey Smith

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78243-308-8 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-317-0 in e-book format

Cover illustration and design by Aubrey Smith

Illustrations by Aubrey Smith

Designed and typeset by Claire Cater

www.mombooks.com

CONTENTS

For my rascal of boys, Matt, Stanley and Albert.

Stand near woodland in early spring, after night has fallen and when the air is still, and if youre lucky, youll hear the thrilling, trilling song of the nightingale. Perhaps youll be luckier still and hear more than one; male nightingales sing to establish their territory and attract a mate, so if youre walking in a woodland after sunset youll often hear several birds singing in harmony. Its hard to put into words such an ethereal experience, but if you tried, what would you say? What would you call a forest full of nightingales? These days we generally refer to most groups of birds as a flock. Its a practical, catch-all term that is usually adequate for conveying our meaning. But perhaps the timelessness of the nightingales song has stirred something in you; you want to do justice to that proud, hopeful warbling. You think of those half-remembered lines from John Keats Ode to a Nightingale:

Thou wast not born for

death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations

tread thee down;

The voice I hear this

passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown.

In the modern world, those ancient days can seem to belong to another universe. The pace of our lives, the speed of our technology, and the digitization of our human connections would all be unfathomable to our distant ancestors, just as their customs, cures and country lore can seem incomprehensible to us. But those nightingales singing in the twilight connect our two worlds. And so does the language that we use to describe them. In fact, the gradual evolution of our language over the centuries is a reminder that the past and the present are not two worlds but one. Many of the words English speakers use every day have their roots in the language used by the ancient civilizations and most of the sayings and idioms that form part of the lexicon of phrases we take for granted were already proverbial in the Middle Ages. One particularly rich stream of historically resonant language includes the words we use to describe groups of people, animals and birds, properly known as collective nouns. If one of our fifteenth-century forefathers had witnessed that symphony of nocturnal bird song, hed have said hed heard a watch of nightingales.

I love this as an example of a traditional collective noun because it is typical of the way a simple group name can provide a snapshot of the person, creature or thing it describes. A phenomenon American author James Lipton describes perfectly in his distinguished book on the subject, An Exaltation of Larks, as giving us large illuminations in small flashes.

The aim of this book is to celebrate these nuggets of enlightenment, to explore their origins, set them in the social context in which they would first have been used and to attempt to share the view from the window that each one opens onto the medieval world. Why is a group of lions called a pride? Who called a flock of crows a murder? Why is a party of friars, or foxes, or thieves, referred to as a skulk?

Unusually for terms used in the Middle Ages, there is a paper trail to follow in pursuit of the origins of collective nouns. Its a trail that weaves and winds, more country lane than Roman road, but it is there, and this fact alone helps to explain where they came from. Unlike proverbs, rhymes or homilies, these terms were formally recorded because they formed part of the education of the nobility. In fact, they were created and perpetuated as a means of marking out the aristocracy from the less well-bred masses. Most of the traditional collective nouns were aware of today from a gaggle of geese to a kindle of kittens appeared for the first time in fifteenth-century publications known as Books of Courtesy. These were handbooks on the various aspects of noble living designed to prepare young aristocrats for the formalities of their privileged lives and prevent them from embarrassing themselves or their families at court. Unless otherwise stated, all of the terms examined in this book can be traced back to these documents.

The earliest of these documents to survive to the present day was the Egerton Manuscript, dating from around 1450, which featured a list of 106 collective nouns. Several other manuscripts followed: two Harley Manuscripts, the Porkington Manuscript, the Digby Manuscript and the Robert of Gloucester Manuscript, each adding their own terms. Then, in 1476, William Caxton, who had just returned from Germany with the expertise to establish Englands first printing press, published a version of John Lydgates political poem Horse, Sheep and Goose. On the final few pages, in keeping with the hand-written manuscripts that preceded it, he included a list of collective nouns. This was followed, in 1486, by the publication of the most influential of all the lists, which appeared in The Book of St Albans, a treatise on hunting, hawking and heraldry, written mostly in verse and attributed to the nun Dame Juliana Barnes (sometimes written Berners), prioress of the Priory of St Mary of Sopwell, near the town of St Albans.

Print historians have expressed uncertainty over the true identity of the books author, but most seem content with the likelihood that Dame Juliana, who joined the convent from an aristocratic family, was responsible at least for the section on hunting, and for its accompanying list of group terms titled The companies of beasts and fowls. This list features 164 collective nouns, beginning with those describing the beasts of the chase but extending to include a wide range of animals and birds and an extensive array of human professions and types of person. The Book of St Albans was reprinted by the famous printer Wynkyn de Worde and new editions appeared throughout the sixteenth century, spreading the knowledge of these terms far beyond their early, elite audience.

Those collective nouns describing animals and birds have diverse sources of inspiration. Some are named for the characteristic behaviour of the animals (a leap of leopards, a busyness of ferrets), or by the use they were put to by humans (a yoke of oxen, a burden of mules). Sometimes theyre given group nouns that describe their young (a covert of coots, a kindle of kittens), others by the way they respond when flushed (a sord of mallards, a rout of wolves). Others still are named by some personality trait they were believed to possess (a cowardice of curs, an unkindness of ravens). Its these examples that are most revealing of the medieval mind-set of their inventors, as well, of course, as those that describe people. Clearly there was no reason related to hunting that the companies of beasts and fowls should have included terms, many of them humorous, sarcastic or negative in tone, to describe types of people or groups of craftsmen or professionals. The clergy come in for a particularly hard time, with an abominable sight of monks and gamely included by Dame Juliana a superfluity of nuns.

Next page