Table of Contents

To Joanna Macy

in gratitude for her tireless efforts

to preserve and protect the living earth

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

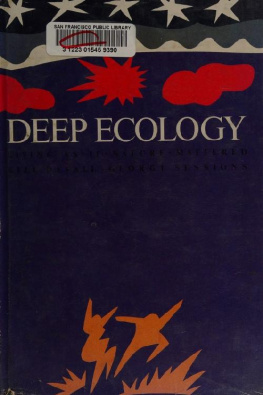

I THANK ALL THOSE who throughout the years have written and acted in defense of the earth, such as the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, E.F. Schumacher, Arne Naess, George Sessions, Aldo Leopold, Annie Dillard, and Joanna Macy, and who have appeared in the pages of this book. And I thank as well others who havent appeared herein but whose influence on my own environmental concerns and philosophy has been profound. Among these some of the most important are the brothers Ronald and Donald Culross Peattie, Wendell Berry, Francis Moore Lappe, Edward Abbey, Terry Tempest Williams, and Masanobu Fukuoka. And Im thankful as well for the profound aspects of deep ecology that pervade the teachings of the Buddha and that have shaped a path of economic restraint and voluntary simplicity for myself and other Buddhists to follow. Once again I thank my wife, Karen Laslo, for her support and guidance not only in matters of writing but in life as well. Karen has shown kindness and forbearance in her toleration of the long hours and days I sometimes spend at a computer when an outbreak of writing has overtaken me. I also want to thank Josh Bartok, editor at Wisdom Publications, for his guidance in shaping this book in its finished form. This is the fourth book of mine that Josh has edited, and with each book my gratitude for his wisdom and insight deepens. Josh believes in what Im doing and, more importantly, he understands what Im doing. He knows where my strengths as a writer lie and where they do not. And when Ive strayed away from the path I was meant to walk, he puts my feet back on home ground once more. Where else would I find an editor with the affection and courage to tell me to take a deep breath and hold on because hes about to suggest cutting three major chapters from a book of mine? After the lightning quits flashing and the thunder recedes and the wind dies down, and after I quit fretting over three months worth of discarded paragraphs and sentences, Im invariably grateful to see that my writing is much the better for this tough love of his. Josh, I cant thank you enough.

EARTH: AN INTRODUCTION

UNFORTUNATELY, I have some unavoidably bad news to report regarding the state of the earth. It cant be helped. It comes with the facts. The truth is were poisoning the planet with our industry, bringing uncountable other species to extinction, and heating up the planet with potentially disastrous consequences. Its enough to break the heart. Its not new. As long as a century and a half ago the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, residing in the coal-blighted suburbs of London, witnessed conditions much like our own:

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears mans smudge and shares mans smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

Hopkins didnt flinch from the harsh truth of what he saw, but he saw as well another truth that might easily be overlooked:

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things....

I read these words here in a twenty-first century American town, and I take heart from the persistent tufts of grass and that inch their way up through cracks in the asphalt pavement of the street outside, and from the backyard dogwood tree that season after season ripens red berries for flocks of waxwings to feast upon. Everywhere I look, I see evidence of deep down things. I might never have become a Buddhist had I not first encountered Zen Master Dogens Tenzo Kyokan or in English Instructions to the Cook. It was the first Buddhist text I ever read, and it engaged me in such a way that I entered the path of Zen and never looked back. Its often said that while the Tenzo Kyokan gives literal instructions on how to cook, its actually an analogue for how to live ones life whatever one happens to be doing. I dont doubt that Dogens instructions can be profitably read that way, but the Tenzo (as the chief cook of a Zen monastery is called) actually spends his hours and days, sometimes years, devoted to the duties of the monastery kitchen and garden. The gardening and cooking of the monastery cook isnt metaphorical, its actual. If I respect, honor, and value the rice and vegetables that come to hand and know how best to prepare them for use by the body, then I know what I most need to know of life. My kitchen work stands as it is without adjunct interpretation. The Tenzo Kyokan is earthy and rich with the growth, care, and use of living things. The work of kitchen and garden is a quintessential human exchange with land.

The nature of that exchange is of great concern to me, and this book was written in an effort to better understand the relationship between society and environment, between the people and land. A wealth of detail regarding specific interactions within an ecosystem is already being compiled through the systematic methods of inquiry utilized by the science of ecology. We humans are involved in that interaction, and what Im after in this book is not so much the data but the condition of mind essential to a genuine human interaction with earth. What has been lost to us that we no longer know how to speak the language earth speaks? What have we forgotten to think or say or do that, could we but remember, would restore our acquaintance once more?

As both a Buddhist and a student of deep ecology, Im struck by how much the two have in common, each exacting of the follower a genuine paradigm shift in perception. For the Buddhist the shift is an awakening to earth as an extension of ones own body wherein the dichotomy of self and other dissolves. For the deep ecologist the shift is a similar awakening wherein earth is realized as one indivisible body comprised of all beings of any sort. In both instances, this awakening is of profound proportions arguing for a shared communal relationship with earth that is unknown in modern industrial society. Of the eight principles of deep ecology as set down by Arne Naess and George Sessions, the seventh principle states the extent of the change required:

The ideological change is mainly that of appreciating quality (dwelling in situations of inherent worth) rather than adhering to an increasingly higher standard of living. There will be a profound awareness of the difference between big and great.

For both the Buddhist and the deep ecologist, quality resides in dwelling itself. Anything that dwellsa stone, leaf, rabbit, the back yard elm tree, my next-door neighborhas an inherent worth not derivative of its value to others. The quality of dwelling resides in its own stead and cant be valued on the market. The difference between big and great that Naess and Sessions cite lies in the fact that bigness is a comparative valuation based on quantity, while greatness comes large or small and its valuation exists outside comparison. In America, our higher standard of living is largely a matter of bigness, a standard external to the inherent quality of life itself. The insistence that the worth of a thing inheres in the thing itself and not in its value to others is what weds Buddhism to deep ecology and distinguishes deep ecology from the science of ecology in general. Its a perception that recognizes the right of all beings to exist simply because they do. Nothing is left out, nothing excluded.