Contents

The Knights Templar

In Jerusalem, in the wake of the First Crusade and its bloody triumph, there was born a religious brotherhood of a kind never seen before. In about AD 1118 this embryonic Order, comprising a handful of men, established itself on the site of the ancient Hebrew Temple. They became known as the Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon , the Knights Templar , or simply the Templars. Setting themselves apart from other knights and nobles, the Templars took religious vows before the Patriarch of Jerusalem. They renounced worldly comforts and committed themselves to a harsh, monastic way of life. It was to be monasticism with a difference, however, for they were to retain their arms and armour and become warrior monks. This union of monasticism and militarism was a new concept within Catholic Christianity, and some observers were troubled by the contradiction. Others were concerned lest the Templars neglect the internal battle against spiritual forces of darkness while they engaged in physical warfare against those deemed infidels and enemies of Christ.

The Templars lived communally, devoted themselves to prayer, and embraced poverty, chastity and obedience. In addition they pledged their swords to the defence of pilgrims, guarding them from the bandits and marauders and guiding and sheltering them along the arduous way to the sacred places. The early Templars received enthusiastic support from Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, the charismatic and visionary leader of the Cistercian Order, who was later to be canonised. St Bernards endorsement resulted in the Templars incorporation into the heart of the ecclesiastical establishment. They received their formal Rule, as well as general recognition by the clergy, at the Council of Troyes in 1129. A great noble, Count Hugh of Champagne, meanwhile, gave the Order an aristocratic seal of approval by joining it himself. He swore allegiance to their founding Grand Master, Hugues de Payens, who had embarked for the East as the counts own vassal. Before long, Church edicts were issued, giving the Templars such extensive powers and privileges that in theory they answered only to the Pope.

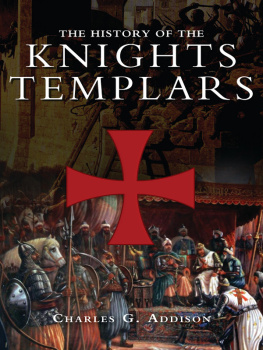

The Holy Land had been recovered for Christianity from the Muslim powers. While enduring much suffering and spilling much blood, the Crusaders had effectively created a Christian confederation there, comprised of the four states of Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli and Jerusalem. The fledgling Kingdom of Jerusalem became pre-eminent, but was surrounded by enemies and remained in peril. The scene of Christs Crucifixion and Resurrection was held sacred by all of Christendom. Once Jerusalem was won, the struggle was to retain it. It soon became clear that the Order of the Temple could serve an additional function contributing to the defence and expansion of the kingdoms frontiers. The Templars potential was appreciated in the principality of Antioch, to the north, where they received some of their earliest castles. Catholics with sufficient means made generous donations of land and capital to the Order. They believed that by making such endowments they aided the Holy Lands physical defence, and also helped to assure spiritual salvation for themselves and their families. Pious nobles proved ready to join the Order as knights, while commoners joined as sergeants or serving brothers. Soon the Templars evolved into a formidable army, spearheaded by knights in white mantles emblazoned with red crosses. An Armenian chronicler wrote of them as Christ-like paladins, who appeared as if sent by Heaven to defend the Christians from Turkish marauders. The Templars martial activities in the Holy Land were facilitated by an expanding support network in France, England and other kingdoms, where soon the Order became a familiar presence in society.

After 1144, when Edessa fell to the resurgent Muslims, the Second Crusade was proclaimed. In the course of this campaign the Templars came of age as a fighting force. They contributed leadership and financial assistance to the expedition of Louis VII of France as it crossed Anatolia, saving the Kings contingent from certain annihilation. At around this time the Order also began to commit knights to battle against Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula, the reconquest of which was coming to be portrayed as a second front in a virtually ongoing Crusade. The Templars and their counterparts, the black-clad Knights Hospitaller, continued to bolster secular armies fighting on the frontiers of Christendom. They fought in Spain against the Almohads and in Eastern Europe against the Mongols, as well as against the Turks, Arabs and Mameluks in the Levant. Their foe was often equally zealous and invariably possessed a significant numerical advantage. On a number of occasions the Templars fought to the brink of their own extinction.

The Templars most famous defeat was at Hattin, against the Sultan Saladin, the nemesis of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Poor and divided leadership not least, perhaps, the failings of the Orders own Grand Master Gerard de Ridefort propelled the Christians towards this disaster in midsummer of 1187. Saladin captured their leader King Guy and (what was worse) the True Cross. The Christians had carried the sacred relic into the battle, as they had into many through the years. After the battle, the Sultan executed his Templar and Hospitaller captives. So many other Christian knights had been killed or taken prisoner at Hattin that there were few left to defend the towns, castles and cities, which capitulated to Saladins might over the ensuing months. Eventually came the turn of Jerusalem, and soon the Muslims again controlled the Holy City.

Europe had not yet lost its Crusading enthusiasm, however. The Third Crusade, led by King Richard the Lionheart of England, restored the coastal cities of the Holy Land to Christian rule. Meanwhile, new knights came to replace the fallen brethren of the Military Orders, who were considered martyrs. The Orders played an active role in the fight back, especially at the Battle of Arsuf, where Saladins army was scattered. The Christians might have followed up this victory by retaking Jerusalem, but realised that they had insufficient men to hold on to it afterwards. Having reached a stalemate, the conflict was suspended and a truce was made.

The Templars avoided participation in the infamous Fourth Crusade, which veered off course and pillaged Christian Byzantium. Likewise they kept out of the Albigensian Crusade, which ravaged the Languedoc in the name of eradicating heresy. They were, though, active in the ill-fated Fifth Crusade in Egypt, and in the Sixth, when the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II secured through diplomacy the restoration of Jerusalem to the Christians. In the second quarter of the thirteenth century an internecine power struggle between the Pope and the Emperor led to political Crusades being preached within Europe against Frederick II himself; Frederick being viewed as a threat to the Papal States, which his domains encircled. The Templars as a rule disdained to fight against other Christians, even on the Popes behalf. In 1244 in the East, meanwhile, allies of the Sultan of Egypt, the Khoresmians, took Jerusalem by storm, and subjected it to rapine and pillage. Soon afterwards the Christians suffered another heavy defeat, at the Battle of La Forbie, where almost all the Templars were killed or captured. Though the Order would again resurge, it was perhaps the beginning of the end.

The Seventh Crusade that of the saintly King Louis IX of France came next. Louis invaded Egypt with Templars as his vanguard, but was not fated to achieve great success. The Templar contingent, after initial triumphs, was decimated when it accompanied Louiss bellicose brother in a fateful charge into the town of Mansourah. The knights were trapped and massacred. The victorious Mameluks, a caste of slaves-turned-warlords, soon seized power. Lauded by a Muslim chronicler as Islams Templars , these Mameluks subsequently burst out of Egypt into Syria and Palestine and, after defeating the Mongols, turned against the Christians. In unrelenting campaigns, they whittled away the territory of the Frankish settlers. Europe, meanwhile, had turned in against itself. Successive Popes were distracted by their wars in Italy and Sicily. They offered indulgences to those prepared to take up the sword for the Guelf cause against the Ghibellines . Papal wars against Fredericks successors absorbed money and manpower, much to the detriment of the Latin East and to the dismay of Templars. The condition of the vestigial Kingdom of Jerusalem continued to deteriorate as the thirteenth century wore on. In 1291, when no Crusaders came to reinforce them, the Templars there perished defending the last corner of the last major Christian stronghold, the city of Acre. They fought on almost until the walls of their fortress tumbled around them. Yet even after this final failure of the Eastern Crusades, the Templars survived as a powerful organisation throughout Europe, at least until the fateful events of 1307.

Next page