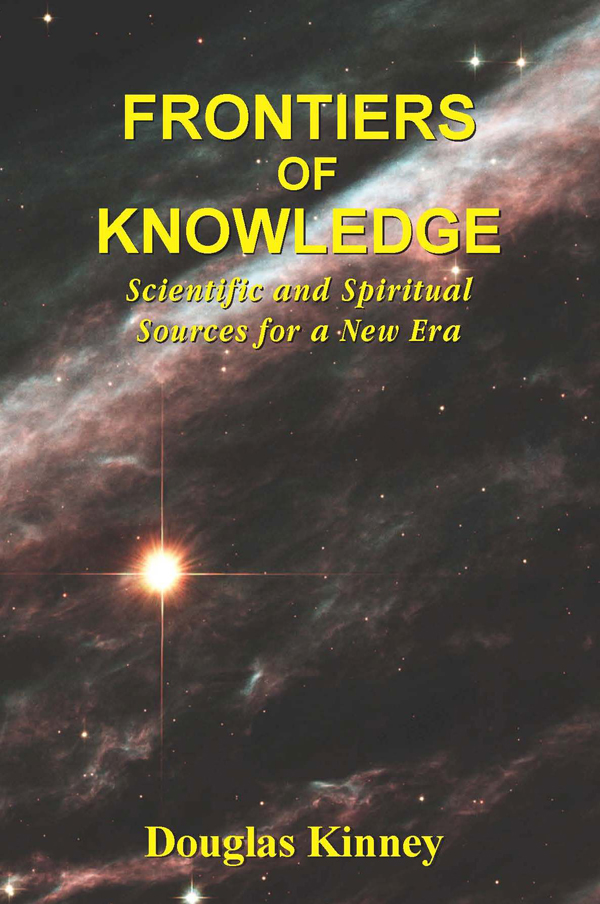

FRONTIERS

OF

KNOWLEDGE

Scientific and Spiritual

Sources for a New Era

Douglas Kinney

Copyright 2014 by Douglas Kinney

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the author.

Published by Douglas Kinney

Printed in the United States

eISBN: 978-0-9912263-4-4

Cover design uses photo from http://www.astronomy-pictures.net/supernova_2.jpg

CONTENTS

Dedicated to all the organizations and individuals who made this book possible: frontier scientists of the Society for Scientific Exploration, visionary physicists, subtle-energy workers, spiritual explorers, especially the spiritual hypnotists, and my wife, Terry, who supported me through the long research and writing process.

Seeing. One could say that the whole of life lies in seeing... But unity grows, and we will affirm this again, only if it is supported by an increase of consciousness, of vision. That is probably why the history of the living world can be reduced to the elaboration of ever more perfect eyes at the heart of a cosmos where it is always possible to discern more.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: The Human Phenomenon

(Translation, Sarah Appleton-Weber, p. 3)

Acknowledgements

I deeply appreciate all of the help, support, and encouragement I have received from many people who during the past few years helped me bring this book to completion.

First and foremost has been my wife, Terry, always the first to read my drafts and provide me with constructive comments and encouragement. She assisted me in the final proofreading of the main text. I want to acknowledge my late brother, Jeff next. He was my first editor, and he helped me find the basic structure for the bookthe right blend of science and spirituality. My second editor, Jeanne Pinault, taught me how to write a booka critical skill for a budding author. My final editors, the experienced team of Sheridan McCarthy and Stan Nelson at Meadowlark Publishing Services, eliminated errors, provided critical guidance, and polished my writingall necessary for a quality product. They were a great joy to work with and their critical eyes and professionalism made the process easier.

I greatly appreciate the frontier scientists, researchers, and explorers who reviewed early versions of chapters for which they are recognized experts: P.M.H. Atwater for near-death experiences, Jim Tucker and Walter Semkiw for reincarnation, and Linda Backman for between-lives spiritual regression. Their critiques and suggestions helped me produce a better book.

The critiques and suggestion provided by two of my friends, Jane Weaver and Herbert L. Calhoun, inspired and guided me at a critical juncture to producing a more integrated, concise, and coherent story. They were my muses. I also want to acknowledge my sister-in-law, Linda Switalski, for her invaluable proofreading help and providing reader feedback.

I would like to acknowledge and thank Jan Price and Ron Scolastico for their kind permission to extensively quote from their published material. Also, thanks to Susan Lewis and John Jacob Baughman for allowing me to share their personal experiences. A special thanks to Peggy Phoenix Dubro for allowing me to use her exquisite painting of the human bodys subtle-energy fibers and the energy shell they create around it.

Foreword

Often, at a considerable distance, we have watched the entire procession across history of mans struggle to address questions about the true nature of human reality. Among many other things, we desire to understand better how a new, more all-encompassing reality is to be conceivedone that takes into account all of the things that we have long known to exist in our world and in our minds eye but that do not seem to be fully accounted for in existing models of reality. We want to better understand how this more broadly framed reality is to best be defined, how it is to be delimited, what its boundaries are to be, and what knowledge bases are to be used to interrogate it. These are just some of the questions Douglas Kinney touches on in this wide-ranging, often freewheeling analysis of what we currently know about reality and how we have come to know it.

As Mr. Kinney reminds us in his introduction, the sharpest edges and most of the flying elbows of the reality debate are often framed as being between what can loosely be characterized as the spiritualist and the scientist camps. Over the course of two millennia, it would be fair to suggest that the spiritualists prevailed for the first 1,500 years of literate Western culture, and at least from the Renaissance up to the turn of the nineteenth century, it would also be fair to say that the scientists have held sway. In this brief span of written human history, we have watched the procession go from a god-centered and god-driven medieval universe, in which the spiritual aspects of mans existence predominated, to a Newtonian clockwork universe where the spiritual aspects have been more or less suppressed.

In the more spiritual, god-centered worldview, man existed under the certainty ofand under the constant watchful eye and hammer ofdivine authority. Still, the god-centered universe was broad enough to encompass all of mankinds fears and demons and the widest extent of his imagination. Its main drawback was never its range but the fact that as a paradigm of our reality, it was weak on explanation, analysis, and understanding. The god-centered paradigm was a noncausal, nonlinear, synchronous world similar to the reality one would expect to find in normal living biological systems. There was no requirement that meanings be attached to logic and reasoning. The god-centered universe also came outfitted with a purpose; it was teleological: it came with the certainty that as a biological organism, the human whole was always more than the sum of its parts. Plus, there was great security and certainty in having a deitys hand on the rudder of human reality. In fact, this alone was seen as enough to compensate for what was missingthe lack of knowledge, explanations, analysis, and understandingin the god-centered model of our universe.

But that all changed with Sir Isaac Newton. In the last five hundred years, the only role the Newtonian clockwork would leave for the gods to fulfill was that of setting the initial conditions for kick-starting the universe. Once it got rolling, thereafter, the wheels of the clockwork began to turn on their own and the Newtonian world became one big computer simulation: everything within the clockwork was not just explainable, but also analyzable and predictable. These, in fact, became important aspects of the new canon of science called the scientific method.

The Newtonian clockwork universe was a linear, causal, reductionist machine. Everything within it could be broken down into its constituent parts; and with rare exceptions, the whole was exactly equal to the sum of its parts. Rene Descartes told us that mind and body were always separate parts of nature, with a permanent barrier between them. Thus in the main, and despite its shortcomings, the Newtonian-Cartesian machine was a very orderly mechanism. Only after a good half millennium of laps around the cosmological track, at the turn of the twentieth century to be exact, did cracks begin to appear around the edges of the Newtonian model of reality.

Einstein led the wrecking crew that brought an end to the Newtonian machine. His relativity theories and the quantum theory he helped fashion pointed unerringly to a host of exceptions to the well-established Newtonian rules. What he and his colleagues discovered came as a package of anomalies and exceptions that still bedevil most scientists even today. As Mr. Kinney makes clear in Part 1, it is these anomalies and inconsistencies that forced a reopening of the floodgates over which new bridges for connecting the old and new realities into one unified model could be built.

Next page