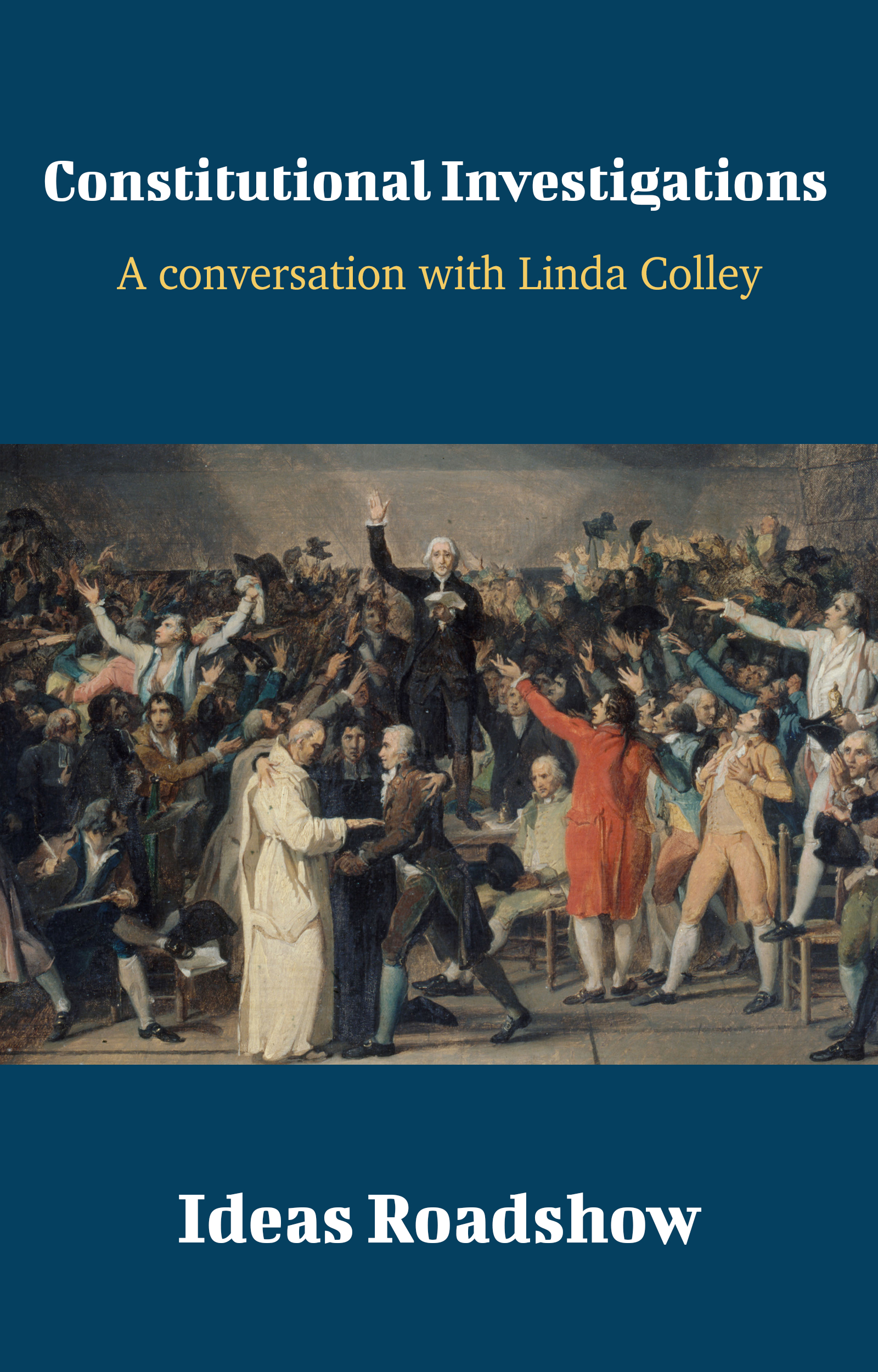

The contents of this book are based upon a filmed conversation between Howard Burton and Linda Colley in Princeton, New Jersey, on May 14, 2015.

Introduction

Knowing the Rules

If a tree falls in a forest, and nobody is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

I have never found this childhood conundrum, one that so many people naively associate with the philosophical enterprise, terribly deep or impressive. Of course a falling tree always makes a sound. Sounds, like pretty well all other natural phenomena from earthquakes to gravitational waves, dont have anything to do with us humans.

So thats one problem solved.

Talking with Linda Colley, however, presents a rather different sort of philosophical inquiry that decidedly does have to do with us humans: If everyone is convinced that a constitution exists even if it isnt actually written down anywhere, does it exist?

Im not at all sure what the answer is to that one.

Linda, the Shelby M.C. Davis 1958 Professor of History at Princeton University, has given a great deal of thought to constitutions and their impact, a line of inquiry that was triggered by her personal experiences of being a Brit who has long lived and worked in the United States.

I think my interest in what are called written constitutions, or codified constitutions, is something that has evolved as a response to my being in the United States, but also as a response to being British, where one is told that written constitutions are something rather exoticwe dont have one.

One of the things I wanted to do was look at the spread of constitutions, almost like the spread of the novel in literature, across the globe. This is a huge cultural shift. Why do people start taking these texts for granted? What does it mean that people start publishing them, and reading them, and teaching them in schools, and sticking them on the walls? This is a really interesting shift in human behaviour over time and over boundaries.

So I was intrigued by them generally, but I was particularly intrigued because it was clear to me, coming from Britain, that there was so much misunderstanding concerning them, even in regard to Britain.

Take the whole concept of Britain having an unwritten constitution. That phraseunwritten constitutionis hardly used in Britain before 1850. People simply didnt think in those terms.

And they still think not in terms of a single, codified constitution, but of a constitution that is crucially dependent on really significant texts like Magna Carta, the Petition of Rights, the Bill of Rights of 1689...

For me, at least, its those tricky little three dots at the end that really represent the nub of the problem. If what we mean by a constitution cant be precisely delineated, if we cant be completely certain what is in it and what is not, then we can never be completely certain what the fundamental rules of the land actually are.

But then, you see, Im not British.

For Lindawho is, but nonetheless well appreciates my sense of bafflementthere is much more in the way of nuance, as you might expect from one of the worlds leading authorities on the history of constitutions and their impact.

A very clever British judge once said that the British constitution was not so much unwritten as it was difficult to find. And the fact that it is difficult to find is part of the problem, as far as I am concerned.

Certainly there are sets of iconic texts, theres the common-law tradition, there are all sorts of Parliamentary Acts, but for me theres a problem, because unless you are a really expert lawyer trying to sort all this out, its very, very hard.

So there is a problem: an interested British citizen wanting to know what his or her constitution is cant download it, cant get it from the library, it isnt contained in a single volume. I regard that as anti-democratic. Not everyone would agree, but my view is that thats a wrong idea.

Lest you think, however, that the way forward is eminently straightforwardthat simply writing things down explicitly guarantees that we all march off towards a shining sea of moral progress, replete with an inherent respect for human rights, civil liberties and all the restthink again. Constitutions, Linda pointedly reminds us, in many ways need to be looked at as tactical documents, means to an end, which have been used for all sorts of purposes in the past, from independence from foreign interference to the expansion of colonial empires, promotion of human rights to their active suppression.

Written constitutions have been, almost from the beginning, multipurpose documents. You can see them as rights documents, you can see them as limiting documents on the executive, and so forth. That isnt wrong, because there are often those components in them, but they also have a dirigiste aspect to them, a capacity to shape people and their thoughts. Like any human political technology, can cater, in practice, to many purposes.

Writing things down, in other words, may well be a particularly helpful way to ensure that all citizens have a clear understanding of what the laws of the land actually are.

But they are no guarantees that those laws are, in fact, just ones.

The Conversation

I. Personal History

Grappling with identity

HB: Id like to start off with asking you about your past and how you became a historian. Were you interested in history as a child?

LC: I think I was one of those children who, very early on, liked writing storiesalthough I suppose a lots of kids do thatand I always liked reading. In retrospect, I am one of many historians who could just as happily have gone into studying literature, but I wanted to keep the novels and the texts that I valued free from academic analysis, so I decided that literature would be a pleasure, but historywhich is also a telling of stories and a curiosity about peoplewas what I wanted to do professionally.

In addition, I was very lucky in having a succession of very gifted history teachers when I was young; and then as I moved into universities I met a succession of scholars who had a great deal of influence on me.