The contents of this book are based upon a filmed conversation between Howard Burton and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill in Cambridge, England, on March 22, 2013.

Introduction

Historical Value

Looked at through the eyes of an archaeologist, human catastrophes can take on a rather different hue.

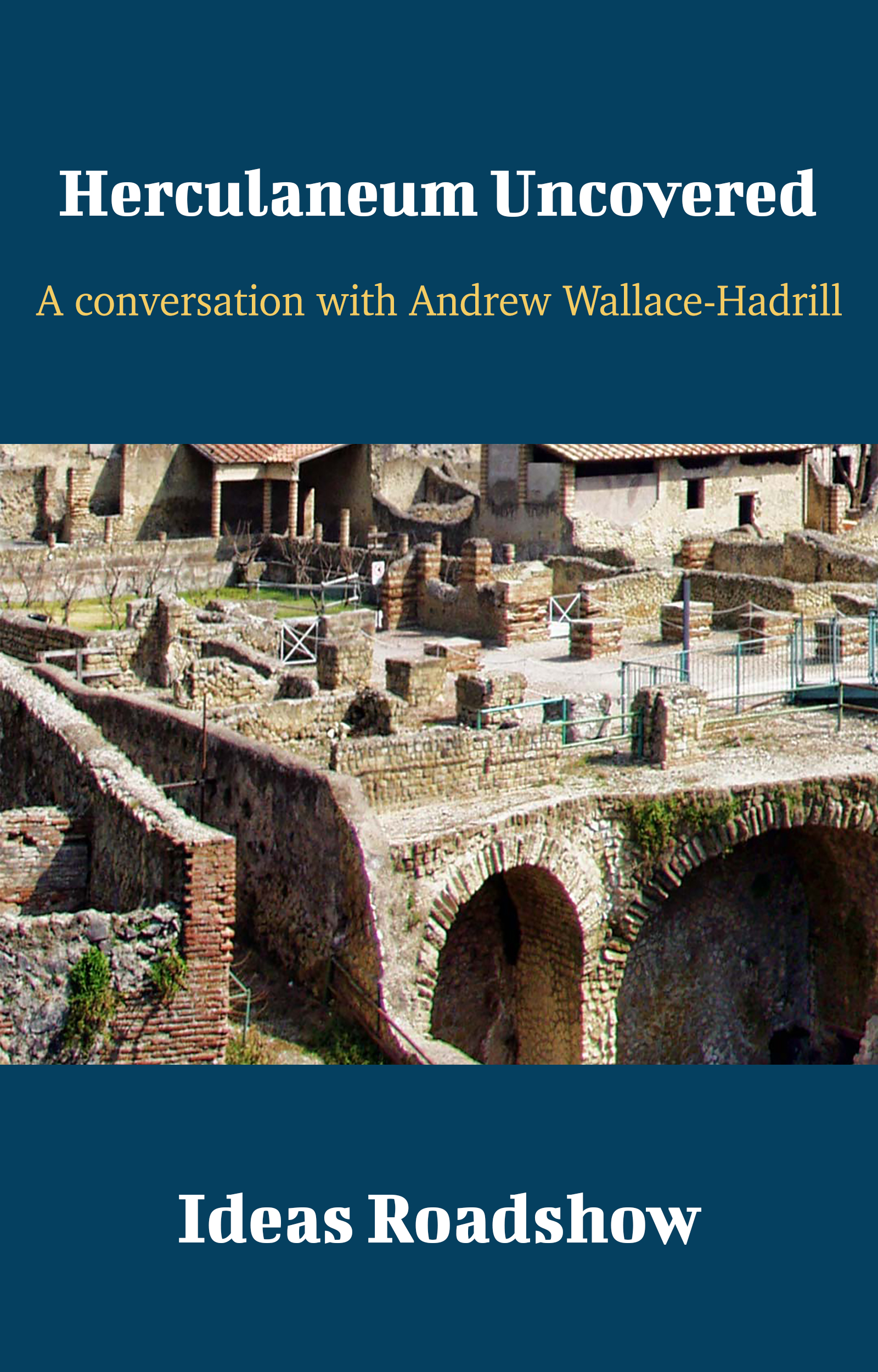

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE, it swiftly engulfed the nearby cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum in an overwhelming torrent of rock and ash. What was an unimaginable nightmare for the two cities inhabitants, however, later became a boon to historical scholarship as the disaster meticulously preserved two separate instances of first-century Roman towns for future generations.

Small comfort for the ancient residents of the Bay of Naples, one would imaginenot many of us would be willing to cut our lives short to satisfy the curiosity of archaeologists two thousand years in the future. But then, its generally acknowledged that living right next to a volcano does tend to shorten ones odds in the great casino of life.

Whats rather less appreciated, however, is that uncovering the past can be just as random and unpredictable a process as burying it.

University of Cambridge archaeologist Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, longtime head of the Herculaneum Conservation Project and past Director of the British School at Rome, is quick to point out societys sometimes quixotic relationship to the past.

His book, Herculaneum: Past and Future, has an entire chapter on The Politics of Archaeology where he describes how the rediscovery of Herculaneum and Pompeii in the first half of the 18th century was a perfect propaganda fit for Charles Bourbon of Spain who was keen to establish his new Kingdom of The Two Sicilies as an integral spot on The Grand Tour as a focal point of global culture. Subsequent periods of languishing disinterest were punctuated by periodic resonances of archaeological and political agendas, featuring Italys post-Risorgimento government and again during Mussolinis fascist regime.

But while the triumphant invocations of national heritage is an all-too-typical part of most government propaganda, Andrew intriguingly describes how in several cases throughout history the exact opposite happened, as the past was deliberately forgotten.

A good case in point is supplied by the relatively recent excavations at Pozzuoli, a 17th-century city at the north end of the Bay of Naples that was built on top of the abandoned old Roman town of Puteoli.

Not surprisingly, the excavators found quite a lot of statues. Of course Puteoli was a major Roman city and naturally there were loads of statues.

But the odd thing that they spotted was that the statues had been deliberately abandoned there in the process of backfilling the site in order to build the new city on top. That is to say, the people who backfilled it knew that they were throwing away ancient statues.

And I was really struck by that, because then I thought, Ah. The interesting question is not just, Why do people excavate and look for the past? but, When do they not want to find the past?

And then I put that together with the well-known fact that, at the end of the 16th century, in the 1590s, a major architect called Dominico Fontana dug a big canal to bring water from the mountains behind through to the area of Torre Annunziata, which is just by Pompeii. And he sent his canal right through the ruins of Pompeii.

You know, constructing a canal is no minor engineering work. We can see the canal going right through the site with absolute clarity and it cuts a very impressive section through the southern part of the city. There is no way he didnt know that he was finding Pompeii. And yet, nothing was said about it.

Thats in the same sort of time frame of people who actually bury ancient statues rather than dig them up. The obvious guess is in the times of the Inquisition you really dont want to find pagan antiquity. But the difficulty with that interpretation is that during the same period in Rome they were quite involved with finding pagan antiquity, like the Laocon Group seen by Michelangelo.

Maybe, in the south, in the Spanish-dominated south, they were more against paganism or what have you, but for whatever reason, they found Pompeii, they found Herculaneum, and they didnt want to know about it. And that, to me, is as fascinating as the people who did want to know about it.

And suddenly, you see, youve got to explain why they want it. Its not obvious that people want to discover the past. They want to discover the past because its useful to them.

All of which might lead you to naturally wonder whether or not, generally speaking, the past is useful to us.

The modern-day visitor to Herculaneum or Pompeii would certainly be tempted to think otherwise. The sites are generally acknowledged to be in a dangerous state of disarray, with expert voices consistently warning us that, without a well-coordinated national and international effort, we are running a serious risk of having these great archaeological treasures simply erode out from under us.

I think its deeply built into our picture of archaeology that its somehow a way of rescuing the past, that youre saving the past by digging it up.

Well, youre certainly saving it from oblivion in that you didnt know anything about it until you dug it up. But in terms of its own survival, the best place for archaeological remains to be is where they are: underground. Theres nothing that preserves something so well as stable conditions of burialon the whole, burial produces stability.

You think that by digging it up youve saved it, but you never dig up something that is capable of standing on its own two feet. You have to intervene at once in order to ensure that it doesnt crumble under your eyes.

And so, in a very interesting way, the process of excavation is a process of conservation and restoration: you must do something with it.

Reasonable enough, you might be tempted to agree. But then what, exactly, should we be doing?

Well, as you might expect, the situation at Pompeii and Herculaneum is greatly complicated by several overlapping layers of government bureaucracy along with a welter of additional international interests.