The contents of this book are based upon a filmed conversation between Howard Burton and Richard Janko in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on April 30, 2013.

Introduction

Discovering the Past

Everybody likes a good discovery: a new author, a new holiday spot, even a new restaurant. But for a professional academic making a discovery isnt just pleasant: its little short of essential, an integral aspect of how ones entire career is judged.

Just what we mean by the term, however, can range all over the map.

In the natural sciences, the goal is simply to unveil something new about the world around us. Either through encountering new phenomenauncovering an unseen species or exoplanetor, more ambitiously, by constructing dramatically improved explanations of what weve already experienced, such as Darwins theory of evolution or Einsteins theory of relativity.

Mathematicians are convinced that they make discoveries too, but tend to be fairly squeamish about pressing the point, given that such talk puts them on naturally slippery metaphysical ground: just where might this land of mathematical discovery be, exactly?

And then there are those whose land of discovery is firmly rooted in the past.

Economists are a famous example of this: their consistently lamentable foresight is stunningly compensated for, or so they like to assure us, by their uniquely qualified ability to interpret what has already occurred.

Rather more rigorously come the historians and anthropologists. They typically have the good sense to refrain from even attempting to predict the future, concentrating instead on developing innovative frameworks to better understand documented events.

Occasionally, though, past and present collide and new information comes to light that suddenly forces our handsome new object is uncovered, some piece of pottery or manuscript is unexpectedly unearthedand more often than not we find ourselves starkly confronted with tangible evidence that our past assumptions are considerably shakier than we had thought.

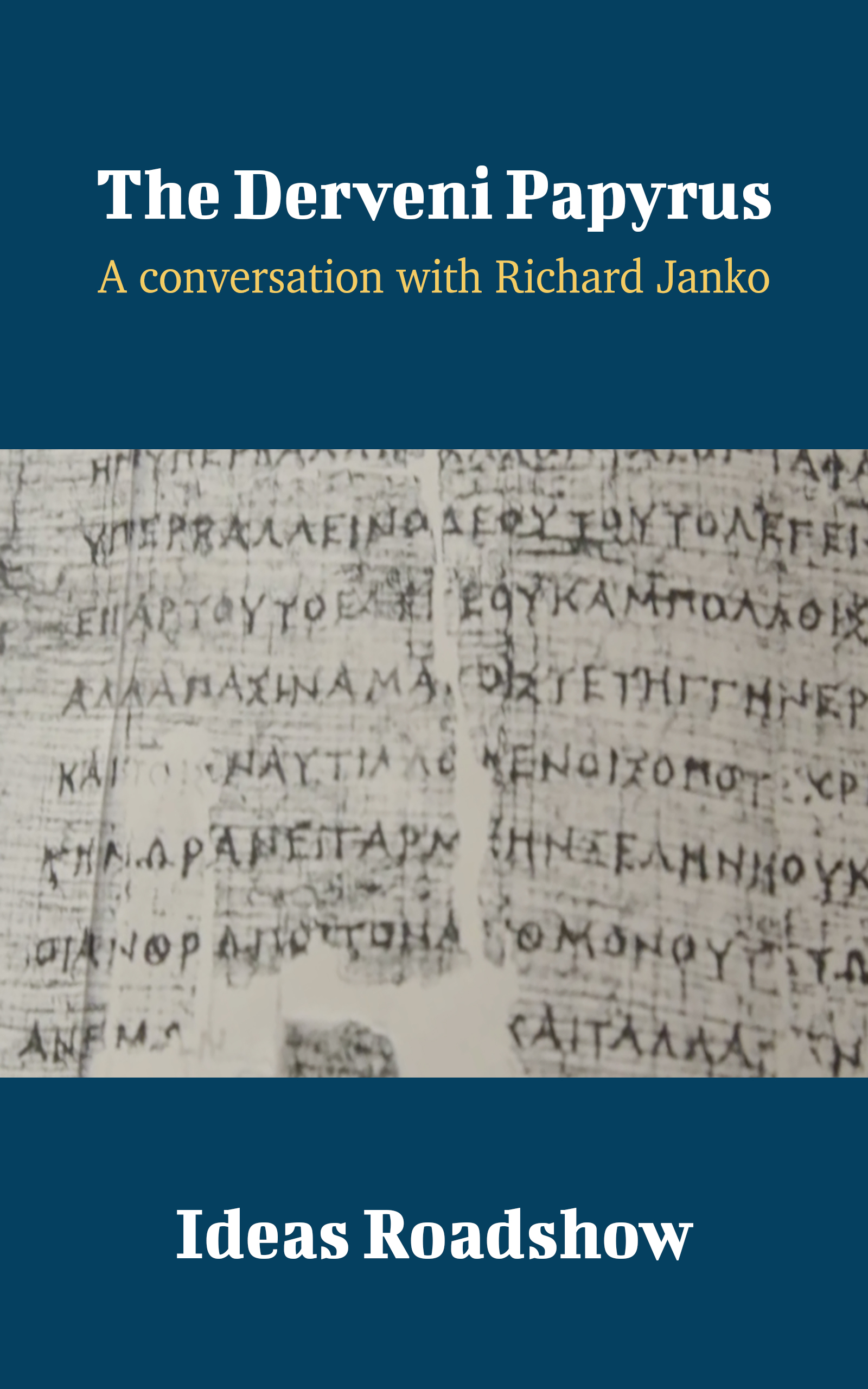

University of Michigan classicist Richard Janko is convinced that this is exactly what happened in Derveni, Greece, in 1962, when a half-burned papyrus was discovered on an ancient funeral pyre. This Derveni papyrus, as it was naturally subsequently dubbed, was eventually recognized to be the oldest surviving European manuscript.

Using a combination of analytic techniques, Professor Janko believes that the scroll was made some time around 350 BCE, and that it is a copy of an original text penned some 70 years earlier, during the Golden Age of classical Athens.

It is hard, of course, to know such a thing with certainty. Ambiguity is a common enough issue in archaeology, but in this case the difficulties are greatly compounded by the fact that few scholars have had a chance to study the work in detail until quite recently: the definitive publication of the text only came out in 2006, a shocking 44 years after the papyrus was found.

Why such an inconceivably long delay to publish the contents of a clearly landmark discovery?

Richard tries his best to be understanding towards those involved, but his decades-long frustration is as evident as it is understandable.

After all, its not just that the papyrus is impressively old. It was also, he tells me, unprecedentedly weird.

This was a wacky book, sort of new-age literature. It didnt seem to say anything that anybody ever expected a Greek text to sayit was completely out of the ordinary. One comparison that Ive heard to explain the bizarre nature of this text is that its as if someone took the Book of Mormon, quoted bits from it, and added the explanation that its actually the theories of Albert Einstein encoded in the Book of Mormon.

Seriously wacky indeed.

But the reason Richard is so excited about the Derveni papyrus is hardly because he believes its simply the ravings of some peculiar fanatic, but for quite the opposite reason: that its contents point to a deep societal schism that until now has been significantly unappreciated by historians and classicists.

According to him, the papyrus was the work of one Diagoras of Melos, a former poet who turned loudly against the gods after having had one of his poems stolen.

Well, what else is new? you might think. After all, poets are notoriously touchy.

His point, however, is not simply that one plagiarized poet had his nose out of joint, but rather that his text illuminates a growing secularist movement that contained the likes of Anaxagoras, Diogenes of Apollonia and, perhaps even more significantly, Socrates.

The primary subtext of the message of the papyrus, he maintains, asserts that state-sanctioned religious tales are not to be taken literally, instead subtly advocating for the development of a more dispassionate scientific method.

That, I think, is what the papyrus was trying to do. It was trying to say, Well, heres this text by Orpheus, which is even more scandalous than the other religious books, saying things like Zeus raped his mother. And I can explain that. It doesnt actually mean that Zeus raped his mother, it means something like, Air separated the elements out and made the sun.

I think that Diagoras was trying to explain the traditional religion in terms of these scientific theories. So what weve got in the papyrus is an explanation of traditional religious practicesnot only the poem of Orpheus but theories about what happens in the underworld after we die, what ghosts are and so onin terms of the modern physics of the time.

Most Athenians, however, werent terribly interested in having their gods limited to a metaphorical backdrop.

Anaxagoras, despite his towering reputation as one of the greatest thinkers of the age and an intimate of their long-standing leader Pericles, who spoke in his defense at the trial, eventually found himself exiled from the city for his impious views.

Years later, the Athenians once again brought impiety charges against another celebrated thinker. And this oneSocratesthey notoriously put to death.

For Richard Janko, these two events were hardly isolated incidents, but instead reflect a steadfast societal determination to turn away from scientific thinking back towards religious orthodoxy, a determination that only hardened once they had done away with Socrates.