Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

4035 Park East Court SE, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49546

www.eerdmans.com

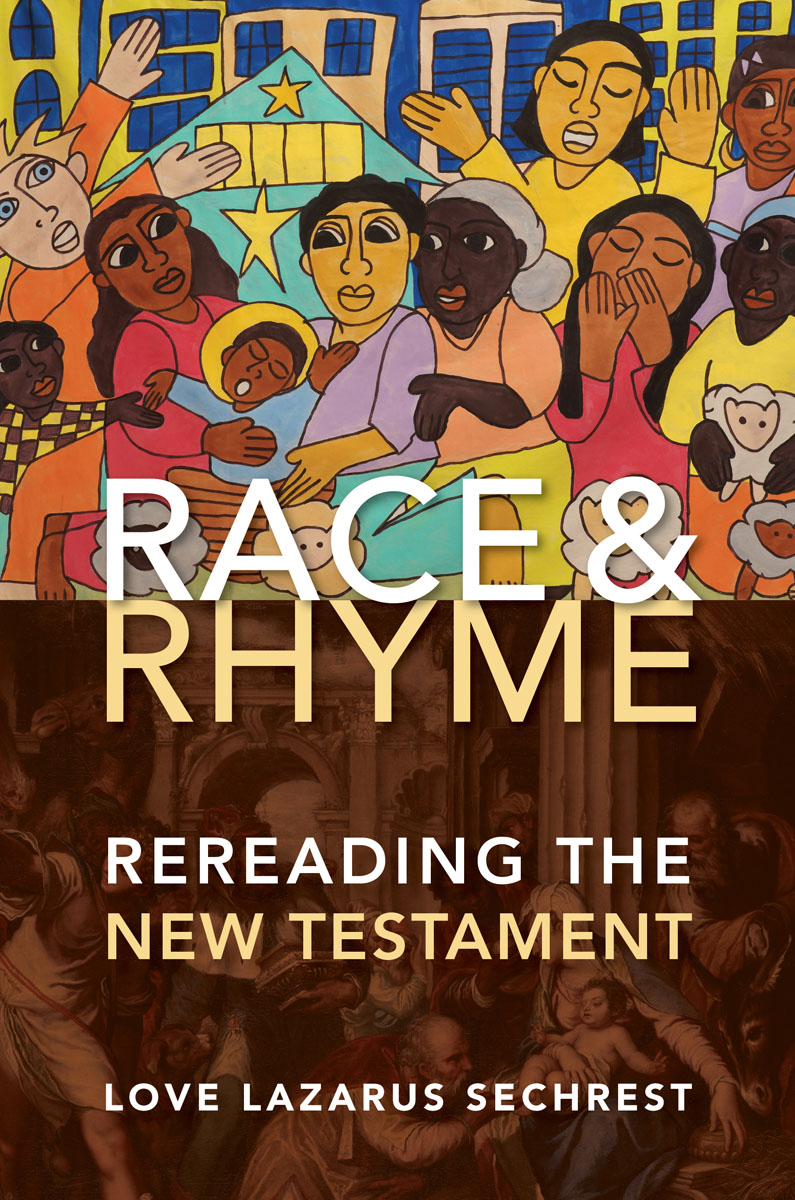

2022 Love Lazarus Sechrest

All rights reserved

Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 221 2 3 4 5 6 7

ISBN 978-0-8028-6713-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

is used with the permission of Wipf & Stock Publishers. A version of this chapter originally appeared as Enemies, Romans, Pigs, and Dogs: Loving the Other in the Gospel of Matthew, Ex Auditu: An International Journal of Theological Interpretation of Scripture 31 (2015): 71105.

Between Ourselves, copyright 1976 by Audre Lorde, Outlines, copyright 1986 by Audre Lorde, School Note, copyright by Audre Lorde. From The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde by Audre Lorde. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

To Paige and Audrey.

Thanks for all youve taught and for all youve forgiven.

You are a constant source of inspiration and hope.

CONTENTS

FIGURES AND TABLES

PREFACE

In this book, I have described and attempted to model a disciplined method by which we identify and analyze situations in contemporary life that rhyme with the situations addressed in the Bible. The method is the one that Ive engaged over fifteen years of teaching students to cultivate a biblically shaped imagination for use in moral reasoning about race relations in the United States. It has been profoundly moving to watch students adopt a posture that takes the Bible and their racialized social contexts seriously while eschewing easy moralistic answers. I have learned much from their struggles to do the imaginative, imprecise, and messy work of challenging their own associations and finding fresh ways to live out the faith.

While this book was gestated and born during my years teaching on the progressive edge of evangelicalism, I have always had a complicated and often uncomfortable relationship with this movement. Evangelicalism is effectively blind to matters of race and privilege and rampant with prejudice against sexual minorities. Politically the movement foregrounds the interests of the unborn, while my politics are equally one-sided in emphasizing the interests of living Black and minoritized bodies. While teaching among people who shared my love of the Bible and my belief that it ought to make a difference in how we live, I found many in this movement who imprisoned the text in the past. Some of these interpreters were preoccupied with theologies that miss the weightier matters of justice, dignity, freedom, and grace that should mark the lives of every disciple. And it is this concern for justice, dignity, freedom, and grace in real life that first drew me to interactions with interpreters who read the Bible through the lens of their own cultural experience. Although many in this school lacked my presuppositions about the Bible, I soon realized that they frequently saw things in this holy and beloved book that others didnt. When I didnt agree with them, I soon learned that I couldnt dismiss them. Sometimes their readings were troubling; other times they made my heart soar. I was eventually utterly captivated by their ways and now count myself among their number.

Though I began working through the lens of a hermeneutics of trust, there was a dawning recognition that trust did not entail, at least for me, willful blindness. What I offer here is an attempt at balancing two convictions: My love for the God of the Bible on the one hand and my distaste for trying to save a text and make excuses for it on the other, as if God needs me to do that. So when some manner of the peace I made with this text or that fails to persuade, so be it. After all these years of wrestling, I was bound to publish or risk not agreeing with the self who began this journey. When I did my doctoral studies in the early 2000s, it was nearly impossible to do African American or womanist biblical interpretation. There was a lack of available mentors, few publishing outlets, and broad marginalization of this work in White-normed interpretive circles where there is scant acknowledgment of the influence of the interpreters social location on the production of meaning. Though I had wonderful mentors and friends in those days, no one was available to me in my field who could help me navigate the marginalization of womanist and African American voices in biblical studies. My own womanist voice did not begin to emerge until many years after graduation, and I am still in the process of becoming.

Though I have the discipline-spanning curiosity of the medievalist, I also share a modern academics disdain for the dabbler. While I attempt to read widely in the disciplines engaged in the various chapters, I necessarily fall short of mastery. Still, I hope that specialists in these respective fields may discern my attempts to avoid the most egregious errors. If there is an arrogance here of attempting a monograph that breaches the rituals and expectations of scholarly guilds, it is one I share with my interdisciplinary womanist sisters. I am convinced that reflection on the complex problems of race and gender requires insights from diverse domains of knowledge.

There are many people to thank. I have the deepest gratitude and never-ending love and admiration for my partner and husband, Edward A. Sechrest Jr., a prince among humans. My two daughters, Paige Allyson Sechrest and Audrey Jordan Sechrest, are brilliant, beautiful, and outstanding leaders each. Boundless love, affection, and thanks also go to my mother J. Rachel Lazarus, my sister Rosalind R. Williams, and the memory of my grandmother Corine Cross Lazarus Hand. All of these family members made me who I am, and because of them, I thank God daily for who Im from. I love you all more than words can say.

I am grateful for colleagues in the African American Biblical Hermeneutics section at SBL, especially Herb Marbury and Randall Bailey, and for longtime friends whose encouragement through the years has meant the world: Willie Jennings, J. R. Daniel Kirk, Mitzi Smith, Joel Marcus, Susan Eastman, Mignon Jacobs, and Reggie Williams. I am no less grateful for new colleagues and friends at Columbia Seminary: for President Leanne Van Dyk, who made it possible for me to get this book over the finish line, every last one of my beloved friends on the faculty, and Karen Wishart-Christian, Ann Clay Adams, and Mike Medford, without whom I would be lost.

Students and colleagues in the Race and Identity in the New Testament course I taught at Fuller Theological Seminary from 2007 to 2018 were essential dialogue partners. All of them have gone on to do groundbreaking work in congregations, non-profits, ethics, theology, law, and education. Im so grateful for Janna Louie, Estella Low Jee Leng, Troy Kinney, Nicole Rivas, Philip Allen, Jeff Liou, Trey Clark, Craig Hendrickson, Nathan Daniels, Jenelle Austin, and Bryson White.

There remains one final note. My first monograph, A Former Jew: Paul and the Dialectics of Race, was among the first to make historical claims about the nature of race and ethnic identity in antiquity, arguing that these social constructions are relevant for understanding the New Testament and other texts in the period. While history is still very much engaged in Race and Rhyme

Next page