A ssembling the material for this book from so many diverse and often ephemeral sources has meant that professional help has been required. Thanks go particularly to Adrian Wilkinson at the Lincolnshire Archives, staff at the University of Hull Brynmor Jones Library, and to several scholars who have paid attention to obscure footnotes in the history of law and the legal profession. One curiosity was the discovery of a history of Staple Inn, with manuscript notes and additions in my copy of Staple Inn and its Story, by T Cato Worsfold: I owe him or her thanks. I have also spoken to various retired lawyers and they have been invaluable in helping a mere layman and enthusiast to grasp some of the intricacies of the law machine.

Preparation has meant much trawling through archives, sending online queries to experts and generally asking obscure questions of a range of specialists. This must necessarily happen when a mere historian sets himself the task of explaining some areas of the law. The sources have been diverse and very mixed, so help was needed all along the way, and it has been no mean task to compile this volume with the lay reader in mind. I have tried to add contextual depth where needed, to explain certain statutes and changes in the law where this will help the researcher into family history.

Specific thanks go to Lincolnshire County Council, County Archives, for permission to use the documents from the Peake, Snow and Jeudwine files (PSJ 12F/A/8) and quarter sessions materials (4 BM/19/8/4/6). Also to the ground-breaking first work on the subject, My Ancestor was a Lawyer, by Brian Brooks and Mark Herber.

Thanks are due to the Welsh Legal History Society, and specifically to Richard Ireland. The illustration here from Brecon is by permission of Richard W Ireland/Welsh History Society.

Simon Fowler was a great help in pointing out the necessity of recasting the format of the book, and so thanks go to him for that assistance.

Finally, the great doyen of English legal history, JH Baker, stands behind this book, as he does behind most writing on the history of the legal professions, and before him, FW Maitland. Bakers work across journals and in his major works will always be worth checking if the researcher is going back beyond the Reformation, and particularly for barrister ancestors.

Chapter One

UNDERSTANDING THE LEGAL

PROFESSIONS

The origins of the English legal system

To understand the nature of the development and definition of various legal professionals, it is necessary to explain the origins of the English law and how the courts developed. Before the courts acquired titles and identities, indicating their special concerns, the common law of England had steadily been created over the centuries, assimilating laws from customs and from the social fabric. Often defined as the common sense precepts from unwritten law, it stands opposite in its nature and tradition from the specific courts developed in the Middle Ages, the idea of equity, which was codified by the Court of Chancery, and also from statute law that law made by parliament.

Therefore, when the Norman Conquest of 1066 led to the centralisation of the regal power and administration, special courts began to be created. The Aula Regis , for instance, was the Kings Court, or Kings Hall was the new centre of the legal justice system. It led to the Curia Regis the later form of the Kings Court, which was the first stage towards the system of eyres and later assizes: varieties of courts on the move across the Kings realm.

The Curia Regis became an institution from which other courts were created: the Court of Common Pleas was an early one, at first being the only superior court dealing with ordinary civil actions, being controlled by five judges and the Lord Chief Justice. The Common Bench was the term for this sitting.

In family research, it is important to grasp the basis from which the later structures came.

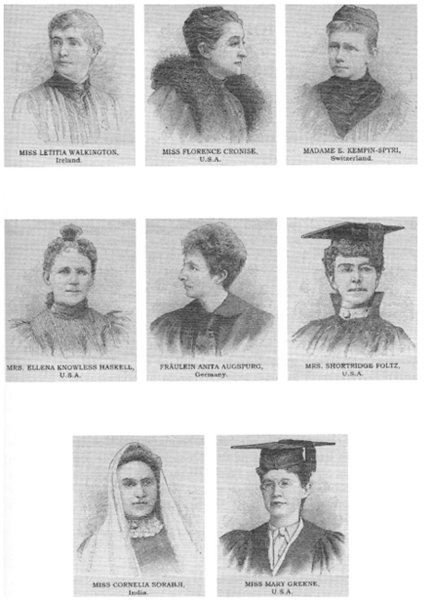

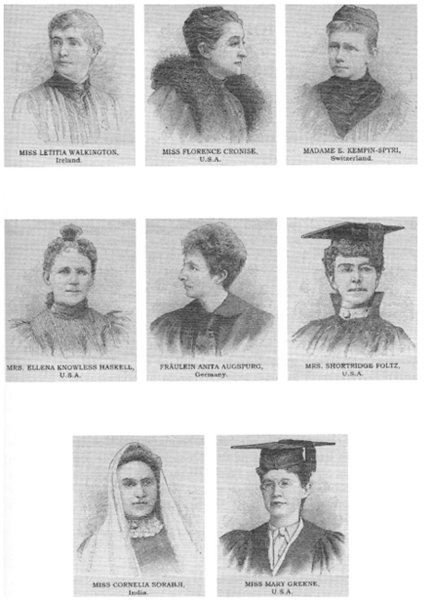

Some early women lawyers in 1890. The Graphic

Examples of early lawyers

In 1200, Stephen Boncretien was appointed as an attorney. After that he was given regular work, and was particularly active in the years between 1219 and 1223. He was a court clerk, appointed for litigation at the Common Bench, and his name appears on the plea rolls the records for those suits. This was a sign that law as a profession, rather than as something that a literate man would dabble in when required, was emerging. In previous centuries, the ecclesiastical courts had naturally had their own staff in legal work, but for lay people in civil and in criminal courts, the practice had been for the plaintiff to take a friend or adviser to help in a court.

In the first years of the reign of Henry III (c.12161244), the serjeants of the Common Bench begin to be recorded. These were learned in the law, and they spoke for litigants; most people at Westminster started to use these serjeants. But more generally it seems that the kings throughout the thirteenth century gave legal work to amateurs who had a solid classical education. As Alan Harding has written, The lawyers of England, by this time, the thirteenth century, are worldly men... but they are in their way learned, cultivated men, linguists, logicians, tenacious disputants, true lovers of the nice case and the moot point.

Judges began as councillors to the sovereigns; the Kings Bench needed justices (and the King at times) to sit, and so this became a central source of the judiciary. Common law courts had so-called barons and chief barons to preside. But judges emerged as men who had a special training and an example of this would be Ralph of Hengham, who was first a judges clerk, then a justice in the eyre (circuit hearing) and finally became a judge in Common Pleas by 1274. By the last decades of the fourteenth century there was an increasing demand for occupations in the law of a lesser degree to that of judge; working with them, a body of experienced attorneys developed across the land in various provinces.

The Middle Ages also saw the emergence of that standardisation of the vocabulary of law: there was law French which made the legal profession more exclusive. A specific argot in a profession is part of its identity of course. More and more, writs and pleadings, the stuff of everyday law, was in the hands of the attorneys.

We have a sharp insight into the medieval lawyer from a very unusual source in The Paston Letters . These cover three generations of the Paston family of Norfolk, through the reigns of Henry VI, Edward IV and Richard III, so the lives of various people in the legal professions come alive there. William Paston, born in 1378, became a judge in 1429, having been a serjeant-at-law by 1421. He had also been a steward of the Duke of Norfolk. His son, John, born in 1421, went to the Inner Temple and was a knight of the shire. A relative, Elisabeth Clere, wrote to John to ask for legal advice and to ask him to consult another lawyer, writing:

Cousin, I let you weet that Scrope hath been in this country to see my cousin your sister, and he hath spoken with my cousin your mother [cousin meant relative at that time]. And she desireth him that he should show you the indentures made between the knight that hath his daughter and him: whether that Scrope, if he were married and fortuned to have children, if the children should inherit his land or his daughter the which is married...

We do not know the outcome, but it appears to have been a complex case, and the essential fact is that they are keeping it in the family this piece of legal business.

The coroner (crowner)