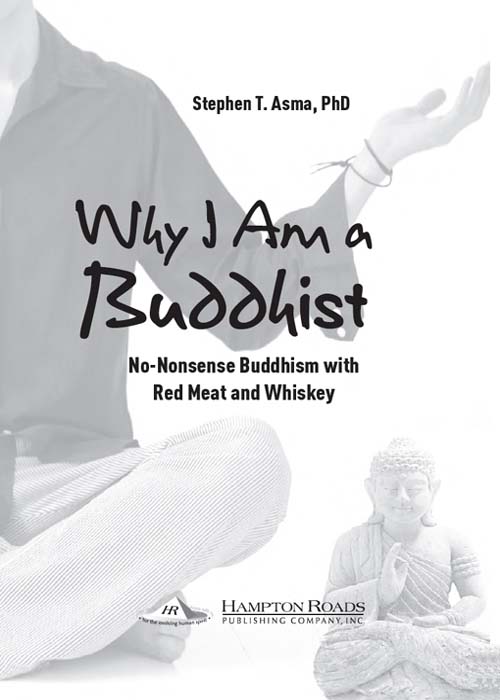

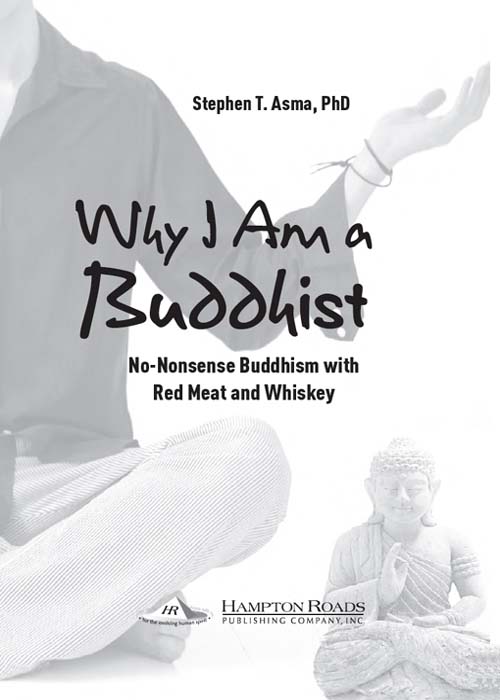

I'm not a monk or even a member of a temple. I have studied Buddhism with some amazing scholars and practitioners and I've taught Buddhism for many years in the States and Asiabut I think gurus are screwballs. I probably drink too much, and I'm not in the least bit interested in sexual abstinence. I like the White Sox and I eat meat. If a guy like me can be a Buddhist...trust me, there's room for you.

from the book

In Why I Am a Buddhist, philosophy professor and author Stephen Asma decodes the often confusing and contradictory impressions that crowd together under the umbrella of Buddhism to show the beneficial wisdom that Buddhism offers for the challenges of modern life. Beginning with the story of his early attempts at achieving mystical experiences with natural and controlled substances as a disaffected teen, Asma traces his exploration of Buddhism and mindfulness, a way to discipline our minds that helps us chart realistic goals and stay on course.

Buddhism attempts to give us a second nature, says Asma, one that writes over the old genetic and psychological code, but it never asks us to pretend that the old code doesn't exist. Unlike some other religions, Buddhism doesn't imagine humans in some unrealistic angelic form. Nor does it cast us as weak and fallen souls, incapable of any improvement save those delivered by an almighty deity. Buddhism acknowledges that we are filled with some pernicious stuff, but we can discipline our minds in a way that liberates us from our tendency to cause suffering, says Asma. The benefits of this approach can be seen in our emotional, social, and spiritual lives.

Learning to apply Buddhism is like learning to play an instrument. It takes a while to get the fundamentalsscales, chords, and fingering technique, says Asma. Then it takes daily practice to learn melodies and progressions. Prolonged failure and frustration are inevitable, but very slowly one begins to hear real music. We don't have to become virtuosos on our instruments or Buddhist sages to appreciate and employ the art form in our lives, but we can't achieve anything without effort.

Stephen T. Asma, PhD, is a professor of philosophy and interdisciplinary humanities at Columbia College in Chicago. He is the author of a number of books, including Buddha for Beginners and On Monsters.

Author photo Brian Wingert

Manufactured in the United States of America

Copyright 2010 by Stephen T. Asma, PhD.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work in any form whatsoever, without permission in writing from the publisher, except for brief passages in connection with a review.

Cover design by Cassandra Chu

Text design by Margaret Smith

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro

Cover photograph liquid library/Picture Quest

Hampton Roads Publishing Company, Inc.

Charlottesville, VA 22902

www.hrpub.com

ISBN: 978-1-57174-617-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

Printed in the United States of America

MV

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992 (R1997).

For my Wen Rong Jinincomparable and always inspiring.

Acknowledgments

As with all my books, I owe a debt of gratitude to my supportive family. Thanks to my parents Ed and Carol, my brothers Dave and Dan, and the extended Asma clan.

This book was written as a challenge from my editor Greg Brandenburgh, and I want to thank him for giving me an opportunity to better formulate my ideas. Caroline Pincus helped me improve the organization of the book. The remaining flaws are entirely my own.

I am grateful to Steve Kapelke, provost at Columbia College; my chair Lisa Brock; and Deans Cheryl Johnson-Odim and Deborah Holdstein. And a tip of the hat to other friends at Columbia College, including Sara Livingston, Garnet Kilberg Cohen, Kate Hamerton, Teresa Prados-Torreira, Micki Leventhal, Oscar Valdez, Krista Macewko, and Baheej Khleif. Special thanks goes to my excellent reading-group partners Tom Greif and Rami Gabriel. Our many readings and discussions indirectly helped to shape this book. And the friendship is invaluable.

Others need to be thanked: Alex Kafka, Kendrick Frazier, Raja Halwani, Gianofer Fields, Pei Lun, Michael Shermer, Donna Seaman, Jim Graham, Jim Krantz, Harold Henderson, Doctor Swing, and the inestimable Academy of Fists.

Finally, I acknowledge my greatest devotion, my son Julien. Tom Wolf once described a son who made the terrible discovery that men make about their fathers sooner or later...that the man before him was not an aging father but a boy, a boy much like himself, a boy who grew up and had a child of his own and, as best he could, out of a sense of duty and, perhaps love, adopted a role called Being a Father so that his child would have something mythical and infinitely important: a Protector, who would keep a lid on all the chaotic and catastrophic possibilities of life. My son won't discover all this for many years yet, but I hope, by then, the myth will have done its beautiful work.

Contents

Introduction

Why I am a Buddhist. If I saw this book on the shelf, I might be tempted to reply, Who cares? I've never even heard of you. Maybe if I were Richard Gere, or Tina Turner, or Adam Yauch of the Beastie Boys, people would muster more curiosity. But even then, readers probably want to know why they themselves should be Buddhists, or at least why they should be impressed with Buddhism. Why should anybody be impressed with Buddhism? Why should we care? How can we benefit from the teachings of a sixth-century Indian philosopher? These are the implicit questions contained in the title of this book. These are the questions I aim to answer.

The title of this book is a positive play on the famous polemical work by Bertrand Russell, Why I am Not a Christian. Positive or negative, praise or critique, such books are attempts to sketch the essence or core ideas of a worldview. Brush strokes are necessarily broad, but hopefully accurate. Exceptions to my generalizations will be inevitable, and the absence of someone's favorite Buddhist story, thinker, or text will be maddening to the initiated. But no matter the flaws of such a format, such a book will hopefully do two things well: first, introduce unfamiliar ideas to the novice, and second, remind and inspire the old hand.

The third possible function of such a personal book is to show how someone applies, or puts into practice, the theoretical teachings. Everyone knows that talking the talk is not the same as walking the walk, and, of course, each person will perambulate a little differently. But one value of such a book is to offer a model (albeit highly flawed) for how to translate the abstractions of Buddhism into concrete, usable life strategies.

Frankly, I probably seem like an odd Buddhist. Whenever I mention it in conversation, people respond with incredulity. Apparently, I should look more diminutive, speak in more hushed tones, and garland myself more with hippy swag. Many Westerners who have adopted Buddhism are remarkably humorless brown-rice eaters, who look like they wake up every morning and say no to life. In short, they are masochistic personalities. But this should not be taken, by the rest of us, as a strike against Buddhism. These characters would practice any religion in the same cheerless manner. I'm not one of these severe Buddhists. I'm not a monk, or even a member of a temple. I have studied Buddhism with some amazing scholars and practitioners, and I've taught Buddhism for many years in the States and Asiabut I think gurus are screwballs. I probably drink too much, and I'm not in the least bit interested in sexual abstinence. I like the White Sox, and I eat meat. If a guy like me can be a Buddhist...trust me, there's room for you.

Next page