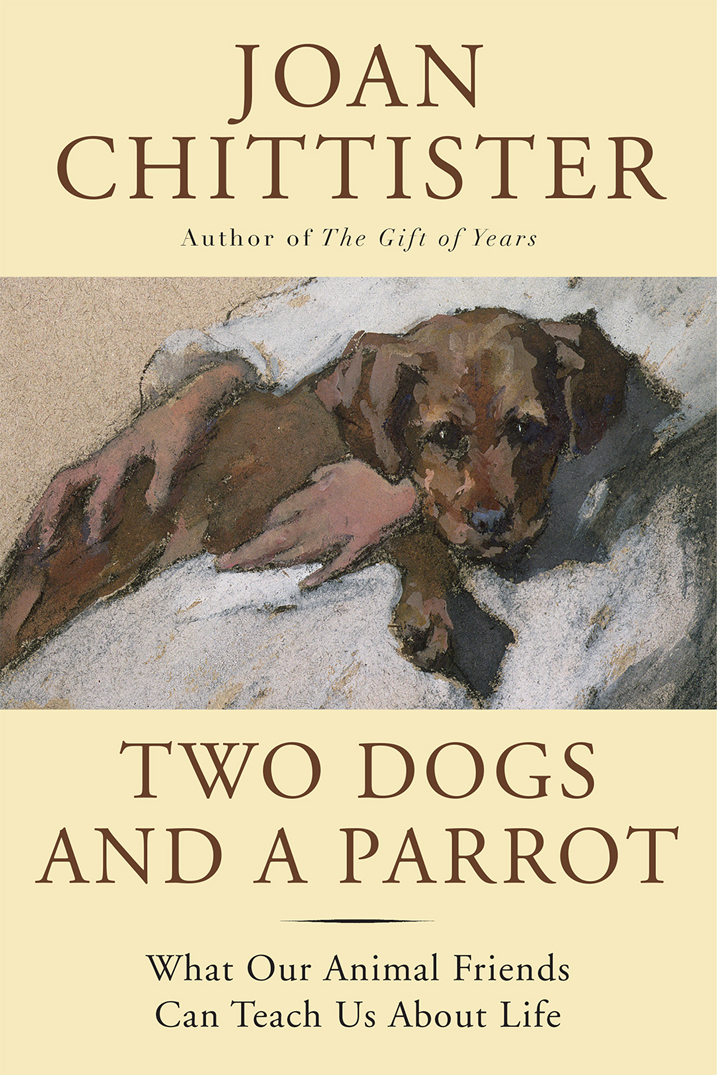

Copyright 2015 by Joan D. Chittister

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Published by

Blue Bridge

An imprint of

United Tribes Media Inc.

Katonah, New York

www.bluebridgebooks.com

ISBN: 9781629190105

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015945910

Jacket design by Stefan Killen Design

Cover art: Friends, Forbes, Elizabeth Adela Stanhope (18591912) / Private Collection / Bridgeman Images

Text design by Cynthia Dunne

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

A ll my life I wanted a dog. After all, I was an only child. To a child without neighborhood friends, without sisters who could become eternal confidantes, without brothers as co-conspirators in life, a dog was the only obvious substitute for companionship. Or at least it was obvious to me. It was not at all obvious to my mother. Our house, my mother insisted, was not the kind of place where dogs belongeda walk-up in a northern city given to lake-effect snowstorms. And furthermore, the landlord agreed with her.

But my mother could deal with the idea of my having a bird. On Good Friday, Billy, a blue parakeet, became the Easter gift of my life. Nothing has ever quite matched it since.

I couldnt take a bird for a walk, of course, as I had seen so many children my age do with their dogs. And we couldnt play ball together. But, on the other hand, I learned that having a bird meant having a companion where the interaction was more intense than it was with a dog. Dogs, at least to some extent, had a life of their own. Billys whole life, on the other handevery drop of water, every bite of food, every ounce of attention, every bit of playdepended on me. It was an amazingly warm and personal thought. It grew me up in ways I could never have expected.

Joan, my mother said, you taught that bird to eat out of your hand. Now you get home here and feed it. So, I quit the swimming lessons that were not half as important to me as Billy was, and did. Billy became my playmate, my ally, my first guide into the depth and meaning of the animal-human bond.

Billy came and filled my empty hours, learned to talk to me a little, flew to my finger when I called her off the curtain rods, woke me in the morningand then, several years later, simply disappeared one day. And broke my heart.

No one knew how it had happened or where shed gone. I only knew that, at the age of thirteen, I had lost something irreplaceable.

All over the world, everywhere, humans and animals form great bonds that give them both another kind of gift of life. Which is one of the reasons Im writing this book. Nevertheless, I hesitate to begin it. A book of this nature brings with it a kind of intimacy and spiritual insight that seems to demand a special kind of privacy. After all, if you begin to talk about your pets as if such talk merits some kind of genuine attention, spiritual as well as psychological, what will people think?

So, this book has been in process for a long, long time. Years. In fact, I had to go through several levels of spiritual growth myself before I realized that it was, indeed, a book worth writing.

At first, I thought of it as nothing but the opportunity to tell a series of anecdotes about the animals Id lived with in various stages of my life. After all, I had regaled groups for years with stories that smacked of depths far beyond either the usual tales of animal behavior or human appreciation of animal companions. Writing the stories down would simply provide the opportunity for a lot of people who like animals, who have lived with pets, to compare their own experiences to mine. Maybe to have a few laughs. Maybe to cry a tear or two.

Many of the stories, I knew, were funny. But some of them, I also knew, were quite surprising for the level of spiritual insight they brought to my own understanding of the human-animal relationship.

Then, one day, in a public lecture I gave, I found myself beginning to explore the differences between the two creation stories in Genesis that have shaped the consciousness of the Judeo-Christian world for thousands of years. At that point, I suddenly realized that there is something quite spiritually profound in the question of what it means to be entrusted with nature, to live with a pet.

In the first creation story, Adam and Eve, first couple and prototypes of the human race that would come after them, are given dominion over what we call The Garden of Eden.

Who doesnt know the story? Who hasnt heard its conditions and its promises? Who doesnt take for granted the power conferred on humans there? Who doesnt recognize that, as part of the human condition, the story awards humankind dominance and precedence over all other living creatures?

The second creation story, however, far less commonly preachedin fact, commonly overlookedchallenges the reader in very different ways than the first. In this story, God the Creator brings the animals to Adam to be namedwhich, commentators commonly explained, is the proof that Adam had been given power over them.

But, I could see, there are very serious problems with this interpretation.

Scholars tell us that this second creation story, which gives us the naming of the animals, is actually older than the so-called first creation story. It was, in other words, written earlier than the domination story. Only at a later period in biblical history was this creation story about the naming of the animals repositioned. The effect of that kind of editing on the understanding of the nature of creation and its implications for humans has been momentous.

Clearly, the relationship between humans and animals had once held a very prominent place, a very primary place, in the human catalogue of spiritual lessons. The human-animal relationship had once held pride of place in the spiritual agendas of human development. The repositioning of the naming story not only made it secondary to the domination story. It also made the dominance theme seem more basic, more fundamental, to human purpose.

God bringing the animals to Adam to be named was hardly proof of power. On the contrary. Naming is an act of relationship, not dominance. We name our children; we name our friends; we name those with whom we develop an emotional bond. But we do not name them in order to get power over them. We name what is near and dear to us. We name the animals we take into our families, the animals we commit ourselves to care for, the ones we take responsibility for, the ones with whom we develop a personal relationship.

Naming gives our relationships character and recognition and respect. Without doubt, then, the biblical story of naming the animals has both personal and spiritual implications for the way we deal with all the creatures of the earth.

The first creation story is the domination story. It defines the process of creation from one level to another. It gives human beings the right to use the rest of the planet for our own use.

The second creation story is the relationship story. By asserting a particular bond between humans and animals, it inserts us into the animal world and animals into ourswith everything that implies about interdependence.