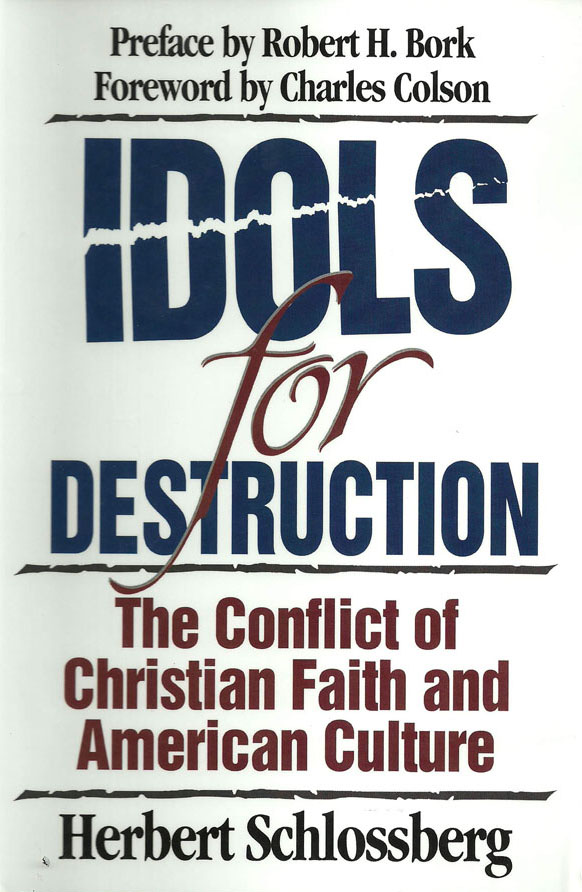

Idols for Destruction

Copyright 1990 by Herbert Schlossberg.

Preface copyright 1990 by Robert H. Bork.

Published by | Crossway |

| 1300 Crescent Street |

| Wheaton, Illinois 60187 |

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by USA copyright law.

Cover design: Dennis Hill

Art Direction/Design: Mark Schramm

First printing, Crossway edition, 1993.

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 13: 978-0-89107-738-1

ISBN 10: 0-89107-738-3

The Bible text in this publication is from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1946, 1952, 1971, 1973 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. and is used by permission.

Crossway is a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

| VP | 19 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 |

| 22 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 |

Table of Contents

I N 1977 I began a serious reading program to learn more about what seemed to me were the most vital and perplexing questions concerning the life of the individual as it relates to the society. These issues had first caught my interest almost twenty years earlier, while I was attending college, but were allowed to lie in dormancy. To my surprise, ideas for a book began emerging from this study and eventually took their present form.

A number of old friends and new acquaintances provided encouragement and criticism, as well as numerous hard knocks, and the book could not have achieved what merit it has without their contributions. Although none agrees with all the ideas expressed here, it is a pleasure to acknowledge the generous help of J.J. Barnett, Richard Johnson, Robert MacLennan, Norris Magnuson, Robert Malcolm, Theofanis Stavrou, Robert Glockner, Guy Chiattello, Michael Gattie, Carl Henry, Ronald Roper, Donald McGilchrist, James Sire, Howard Mattsson-Boz, Lyman Coleman, Randall Tremba, and Wesley Anderson.

My wife, Terry, deserves special mention and thanks. She not only helped revive flagging spirits but made many important suggestions, typed several drafts of the manuscript, and provided the sole support of our family for more than four years while all this was taking place.

T HE technological flowering and economic expansion of the twentieth century has been accompanied by an astonishing growth in pessimism, even despair. The period just before the turn of the century was so charged with a sense of decadence that the phrase fin de suele has come to convey the idea of decline, with a foreboding of doom. Those fears were not groundless, and Europe and the United States plunged into a devastating world war, then a great depression, and then another world war. Those disasters in turn have served to convince many people that Western civilization has entered a period of breakdown from which it may never recover.

The last thirty-five years, though prosperous almost beyond belief, have been visited with social pathologies that reinforce the sourness of those earlier expectations. Our society is now described in such terms as post-capitalist (Ralf Dahrendorf), post-bourgeois (George Lichtheim), post-modern (Amitai Etzioni), post-collectivist (Sam Beer), post-literary (Marshall McLuhan), post-civilized (Kenneth Boulding), post-traditional (S. N. Eisenstadt), post-historic (Roderick Seidenberg), post-industrial (Daniel Bell), post-Puritan, post-Protestant and post-Christian (Sidney Ahlstrom).

Examples abound in which the images of contemporary society have shifted to decline, disintegration, atrophy, and so on. Arnold Toynbee reminisced late in life about his familys expectations around the turn of the century. His scientist uncle was wildly optimistic about the future, anticipating that a golden age was about to be ushered in by science. His social worker father, on the other hand, was rather somber as he contemplated the future. At the time he found his uncles outlook exhilarating and his fathers melancholy. By 1969, however, Toynbee had concluded that his uncle had been naive and his father realistic.

The case of H. G. Wells is more striking because the evolution of his thinking is marked by a trail of books that shows plainly the descending path. His Outline of History (1920) was a song of evolutionary idealism, faith in progress, and complete optimism. By 1933, when he published The Shape of Tilings to Come, he could see no better way to overcome the stubbornness and selfishness between people and nations than a desperate action by intellectual idealists to seize control of the world by force and establish their vision with a universal compulsory educational program. Finally, shortly before his death, he wrote an aptly-titled book, The Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945) in which he concluded that there is no way out, or around, or through the impasse. It is the end. In Wellss journey to despair Reinhold Niebuhr saw an almost perfect record in miniature of the spiritual pilgrimage of our age.

A few examples illustrate the point further. A French Catholic philosopher: The end of the Roman Empire was a minor event compared with what we behold. We are looking at the liquidation of what is known as the modern world.

William Rees-Mogg, former editor of the Times of London, while writing of the hollowness and despair that have gripped Western society, has hope that Americans will escape the general malaise and retain an optimism that will serve to redeem the remainder of the West.

Now, one might object that this outpouring of pessimism reveals the disaffection with society that one expects from intellectuals, and that ordinary people are far less dissatisfied than those chronic complainers. Crane Brinton, himself a Harvard intellectual, made such an argument two decades ago, but it is hard to believe that he would be so certain of that now. A Roper poll commissioned by the U. S. Department of Labor reported in 1978 that, for the first time since that poll was initiated in 1959, the respondents rated their expectations for the future lower than their assessment of the present.

Of course, all of this evidence is subjective, and one could argue that if objective criteria were examined we would find that everything really is getting better and better just as we used to think, even if nobody believes it. We will have occasion later on to look at some of the objective information at our disposal, but there will not be much to support that rosy view.

Understanding Our Place in History

A society conscious of its place in history is seldom content merely to note changing circumstances with no attempt to evaluate their meaning. Edward Gibbons history of Rome made spatial analogiessuch as rise, decline, and fallcommonplace in evaluating civilizations. In the twentieth century, organic phrases perhaps have become more common, possibly due to Oswald Spenglers influence. Societies are thought of as being born, growing, decaying, dying. Other terms are sometimes drawn from the social sciences or from the requirements of political propaganda. Thus, a society may be said to be coming of age, to be attaining self-consciousness, to be throwing off the chains of oppression, to be entering a dark age, to be entering a golden age.