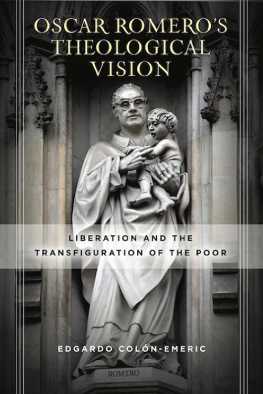

OSCAR ROMERO

A MAN FOR OUR TIMES

JULIO O. TORRES

Copyright 2021 by Julio O. Torres

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

Unless otherwise noted, the Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Seabury Books

19 East 34th Street

New York, New York 10016

www.churchpublishing.org

An imprint of Church Publishing Incorporated

Cover photograph by Victor Manuel Villaran Lopez; used by permission.

Cover design by Marc Whitaker, MTWdesign

Typeset by PerfecType, Nashville, Tennessee

A record of this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-1-64065-349-8 (paperback)|

ISBN: 978-1-64065-350-4 (ebook)

To my mentors and Jesuit martyrs of the Salvadoran civil war:

Ignacio Martin Baro, Segundo Montes, and Ignacio Ellacura

And to my children:

Javier, Elisa, Natalie, Pablo, Orlando, Noah, and Julio Esteban

R arely is a biographer given the chance to examine the life of a person of heroic proportions from the standpoint of his close contemporaries and direct personal knowledge. I was graciously afforded this opportunity when I undertook the task of writing this psychobiography of martyred archbishop Oscar Romero.

This work is an attempt to understand and uncover the humanity of one of the most important religious figures of the twentieth century. In my research, I found out that it is quite remarkable how quickly a personRomero in this casecan become a myth and be elevated to a supernatural realm. Prophets and saints are usually confined to a special kind of Olympus, but they were also ordinary human beings. New Testament scholars have labored for centuries to find the historical Jesus, a task that has turned out to be quite difficult due to the time separating us from him, along with the myriad factors in between. However, because of the proximity of Romeros existence, I was in a much better position to approach the humanity of a saint, as he was proclaimed by the Salvadoran people long before he was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church. I hope to look at the historical Romero as a model for emulation, and to appreciate the quality of his achievement and its significance for our time.

This psychobiography was based on primary and secondary sources. I met Romero when he was still an auxiliary bishop. I was a lay member of JEC (Christian Student Youth). Ironically, in retrospect, he was one of the organizers of a crusade aimed at persuading families to pray the Roman Catholic Rosary. It was around 1970, and a devastating civil war was brewing in El Salvador. At first sight, Romero was simply a pious and quiet clergyman; in fact, he appeared to be rather shy and spoke very little. I dont remember anything he said. His presence at JEC was mainly to support our efforts. He was just there. Romero was not known as a peoples advocate, but as a conservative bishop, and a staunch one at that, which made his change of coursesome would say conversioneven more spectacular. Twenty years after his death, I traveled to El Salvador four times between September 2000 and August 2004 to conduct interviews that became my primary sources. I interviewed all of Romeros surviving relatives, friends, and coworkersmainly clergy. Being a Salvadoran-born American and a priest greatly helped in opening doors and facilitating the interviews. Most people I interviewed appeared interested in the project and were open and candid; I was a padre and they trusted me. For the most part they did not conceal their biases in their evaluation of Romero and the admiration, awe, or even deadly hatred that he inspired in them. They shared a great deal of their time, sometimes an entire day, to help my research.

My interviews were free-floating and informal. I simply took notes and refrained from using a tape recorder to respect the wishes of the interviewees and foster their spontaneity. I began by explaining that I was trying to understand Romero as a human beingnot a religious public figure but a flesh and blood personin order to bring him closer to us. My questions loosely followed the order below, with variations to allow for the flow of the interviewees associations:

When did you meet Monsignor Romero?

What was your relationship to him, and how long did it last?

What kind of person was Monsignor Romero? How would you describe him? (Often I had to prompt people on this point to talk of Romero as a human individual, setting aside the religious transference.)

What do you remember the most about Monsignor Romero? Tell me a story. (In the case of people who knew him as a child or as a young man I would ask more pointed questions about his upbringing and education.)

Anything else you would like to tell me about him? (This last part was usually the longest, since I allowed ample time for free associations.)

My interviews covered a wide range of people including his three surviving brothers, his sister, clergy and lay associates, as well as his closest friend, a traveling salesman with whom I traveled for days at a time. I will refer to them specifically and describe them in detail as they appear in the narrative.

To speak of psychoanalysis as a biographical tool may elicit misgivings about the so-called imperialistic role of psychoanalysis when it purported to be an all-encompassing way of understanding humanity and society. We have come a long way since Professor William Langers famous challenge to the American Historical Association in 1957, when he advocated the use of psychoanalysis as a tool for furthering our understanding of history. The role of psychoanalysis is now understood as more modest but still essential. Robert Jay Lifton writes:

There is a real paradox here, important to keep in mind particularly in historical and cultural studies: without psychoanalysis, we dont have a psychology worthy of address to history and society or culture. But at the same time, if we employ psychoanalysis in its most pristine form, we run the risk of eliminating history in the name of studying it.... [M]ost of history is eliminated in the name of individual psychopathology.... Erik Erikson is a key figure in what might be called a new wave of psychohistory.... What Erikson managed to do was to hold psychoanalytic depth while immersing himself in the historical era being studied and then relating those currents to that figure.

Erik Eriksons seminal work on Luther was one of the main inspirations for this work. He did a masterly analysis of the relationship between personality, historical context, and social and theological impact in the life of the religious genius of the Reformation. He created the model of the great individual in history, that which cannot be explained by any theory, psychological or otherwise, that which is beyond words, and can only, perhaps, be half-way described, as the action of the divine Spirit.

Psychohistory is an essential tool for historians because it adds a new dimension to the interpretation of history. In addition to the social, political, and narrative aspects, the clinical art of psychoanalysis can shed light on the emotional forces that propelled individuals to act in response to their historical context. Instead of appealing to the common-sense explanation, or leaving great lacunae as far as the emotional motivations of the person under study are concerned, psychohistory allows the researcher to add a new layer of interpretation and prediction to their task.