Trbners Oriental Series

ARABIA BEFORE MUHAMMAD

Trbners Oriental Series

ARABIC HISTORY AND CULTURE

In 6 Volumes

I | Arabian Medicine and its Influence on the Middle Ages Vol I

Donald Campbell |

II | Arabian Medicine and its Influence on the Middle Ages Vol II

Donald Campbell |

III | Studies: Indian and Islamic

S Khuda Bukhsh |

IV | A Short History of the Fatimid Khalifate

De Lacy OLeary |

V | Arabia Before Muhammad

De Lacy OLeary |

VI | Arabic Thought and its Place in History

De Lacy OLeary |

ARABIA BEFORE MUHAMMAD

DE LACY OLEARY

First published in 1927 by

Routledge, Trench, Trbner & Co Ltd

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

First issued in paperback 2011

1927 De Lacy OLeary

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

The publishers have made every effort to contact authors/copyright holders of the works reprinted in Trbners Oriental Series. This has not been possible in every case, however, and we would welcome correspondence from those individuals/companies we have been unable to trace.

These reprints are taken from original copies of each book. In many cases the condition of these originals is not perfect. The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of these reprints, but wishes to point out that certain characteristics of the original copies will, of necessity, be apparent in reprints thereof.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Arabia Before Muhammad

ISBN 978-0-415-24466-4 (hbk)

ISBN 978-0-415-51084-4 (pbk)

Arabic History and Culture: 6 Volumes

ISBN 978-0-415-24285-1

Trbners Oriental Series

ISBN 978-0-415-23188-6

ARABIA BEFORE MUHAMMAD

BY

DE LACY OLEARY, D.D.

Author of Arabic Thought and its Place in History, A Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages, etc.

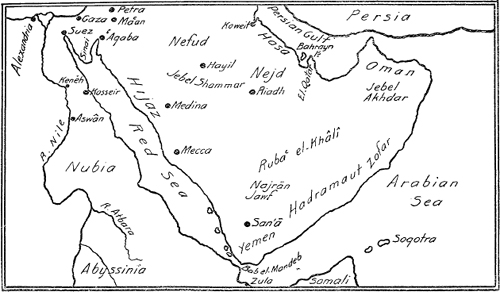

With Three Maps

LONDON

ROUTLEDGE, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., LTD.

NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON & CO.

1927

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

T HE main purpose of the following pages is to show that Arabia, before the coming of Islam, was not a country secluded from the cultural influences of Western Asia, nor was it entirely cut off from contact with the political and social life of its neighbours in the Near East. The result of the ancient penetration of Arabia and the intercourse of the Arabs with their neighbours was that the religion of Islam, so far from taking its rise amongst secluded desert tribes, was a natural stage of development in the religious life of West Asia; and the Arabic language, though spared some of the alien influences brought to bear upon certain other of the Semitic dialects, was very considerably affected by foreign intercourse, even in the earliest stage of which we have written records.

ARABIA BEFORE MUHAMMAD

Describing the conditions of Western Asia Bevan says: Only part of each province counts. The rest is waste landthe desolation of the level desert, the desolation of the mountains the belts between mountain and desert, the banks of the great rivers, the lower hills near the sea, these are the lines of civilization (actual or potential) in Western Asia. The consequence of these conditions is that through all the history of Western Asia there runs the eternal distinction between the civilized cultivators of the plains and lower hills and the wild peoples of mountain and desert. The great monarchies which have arisen here have rarely been effective beyond the limits of civilization; mountain and desert are another world in which they can get, at best, only a precarious footing. And to the monarchical settled peoples the near neighbourhood of this unsubjugated world has been a perpetual menace. It is a chaotic region out of which may pour upon them at any weakening of the dam hordes of devastators. At the best of times it hampers the government by offering a refuge and recruiting ground to all the enemies of order, Between the royal governments and the free tribes the feud is secular. This is a just picture, within certain limitations. Its accuracy is mainly due to the fact that the civilization with which we are chiefly concerned in Western Asia is that known as the river-valley culture based on agriculture of an intensive kind which pre-supposes artificial irrigation fed by a river liable to periodical inundation. Such culture was necessarily limited to the levels to which the water of the river can be raised, and consequently that level becomes the line of demarcation between the settled country and the area of the nomadic tribes. Our earliest records in Western Asia were produced by people of this river-valley culture amongst whom, apparently, the art of writing was evolved. This river-valley culture of Mesopotamia and Egypt has played a very prominent part in history and is the lineal ancestor of western civilization to-day. Still the fact remains that it was but one of several cultural types. It is still unproved that all cultural forms trace back to one source, though the tendency of recent research points strongly in that direction. So far as Western Asia is concerned Bevans dictum holds good as applied to a continuous history which traces back to the social groups of the earlier river-valley culture. Its defect, at least in detail, is that it implies too sharp a line of demarcation between the cultured settlers in the lowlands and the wild denizens of the uplands. There was a constant drifting of the desert men into the settled area, sometimes by way of predatory incursion, but sometimes also by forming settlements where the invaders established homes side by side with the older cultivators and gradually assimilated their culture. One of the best-known instances of this appears in the invasion of Canaan by the Israelites, a confederate group of desert tribes, some of whom settled down to agriculture and formed alliances with kindred tribes who had been earlier invaders and with the older occupants of the country, in spite of warnings and exhortations by their prophets urging them to keep apart. In due course the pressure of Philistine aggression forced these invaders into a closer confederacy, though some of them, e.g. the Rechabite clan of the Kenites (cf. Jerem. xxxv) refused to settle down and remained pastoral nomads to a late period. This invasion appears to be fairly typical of Arab movements into the settled territory, movements which were already in progress at the dawn of recorded history and continue to the present day, sometimes on a small scale, sometimes on a larger one. It is not easy to estimate the physiological results of such invasions. In the case of Palestine there seems reason to believe that the majority of fellain of the present day are descendants of the earlier pre-Israelite and even of the pre-Semitic races. Possibly the moist climate has proved fatal to the majority of the desert invaders who have left their language and religion but have failed to leave a posterity.