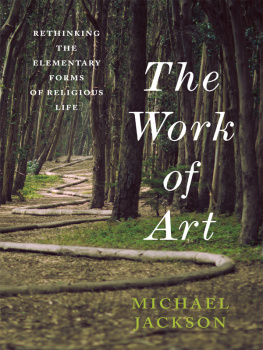

As Wide As The World Is Wise

As Wide As The World Is Wise

Reinventing Philosophical Anthropology

Michael Jackson

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2016 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jackson, Michael, 1940 author.

Title: As wide as the world is wise: reinventing philosophical anthropology / Michael Jackson.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016000265 (print) | LCCN 2016013034 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231178280 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231541985 (e-book) | ISBN 9780231541985()

Subjects: LCSH: Philosophical anthropology. | AnthropologyPhilosophy.

Classification: LCC BD450 J233 2016(print) | LCC BD450 (ebook) | DDC 128DC23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016000265

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at cup-ebook@columbia.edu.

COVER DESIGN: Catherine Casalino

COVER IMAGE: Dimitri Otis / Getty Images

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

The logocentricism of Greek metaphysics will always be haunted... by the absolutely other to the extent that the Logos can never englobe everything. There is always something which escapes, something different, other and opaque which refuses to be totalized into a homogeneous identity.

Jacques Derrida, Deconstruction and the Other

Contents

Between 2009 and 2015, I had the good fortune to participate in conversations and collaborative projects with colleagues in Denmark and the United States on how philosophers and anthropologists might enter into productive dialogue and perhaps find common ground. During this same period I was engaged in ethnographic fieldwork in Sierra Leone and Europe on issues of well-being, migration, ethics, and social justice. While this fieldwork was the dominant influence on my thinking and writing, I was well aware that my existential anthropology ran parallel to the work of many others, so when Wendy Lochner expressed interest, in November 2014, in a book that would explore the interface between philosophy and anthropology, I was mindful of the three books on this theme that I had already had a hand in producing, and wondered what more I could possibly say on the subject. (Those books are The Ground Between: Anthropologists Engage Philosophy, ed. Veena Das, Michael Jackson, Arthur Kleinman, and Bhrigupati Singh; Anthropology and Philosophy: Dialogues on Trust and Hope, ed. Sune Liisberg, Esther Oluffa Pedersen, and Anne Line Dalsgrd; and What Is Existential Anthropology?, ed. Michael Jackson and Albert Piette.) As I took stock of my ongoing research, I realized that some of its recurring themes and most pressing concerns had not found adequate expression in the essays I had contributed to these collaborative volumes. In this respect, my situation exemplified the Sartrean paradox of the singular universal that I explored in my Between One and One Another, namely that the singular I is never completely occluded in any collective activity and the collective has no reality apart from the people who constitute it. As Sartre observes in The Family Idiot, every individual is at once universalized by his or her location in a historical moment yet singular by the universalizing singularity of his [or her] projects.

This perspective offers a novel way of examining the relationship between philosophy, which tends to universalize its subject, and ethnography, which tends to singularize it, and touches on anthropologys oldest dilemmahow to reconcile a focus on particular cultures, people, and lifeworlds with a fascination for concepts that transcend such particular identifications: the human condition, the global, or life itself.

It is in this spirit, responsive to others yet solely responsible for my own thought, that I acknowledge the following individuals and friends, and celebrate the convivial occasions when we came together to discuss what Heidegger called the end of philosophy and the task of thinking: Anne Line Dalsgrd, Veena Das, Kate DeConinck, Robert Desjarlais, George Gonzalez, Ghassan Hage, Chris Houston, Tim Ingold, Arthur Kleinman, Joshua Jackson, Michael Lambek, Sune Liisberg, Marc Loustau, Francine Lorimer, Hans Lucht, Cheryl Madingly, Roberto Mata, Joseph Mar, Anand Pandian, Esther Oluffa Pedersen, Albert Piette, Devaka Premawardhana, Bhrigupati Singh, Jason Throop, Sebastien Tutenges, Mattijs van de Port, Thomas Schwartz Wentzer, Souchou Yao, and Jarrett Zigon.

If philosophy has always intended, from its point of view, to maintain its relation with the nonphilosophical, that is the antiphilosophical, with the practices and knowledge, empirical or not, that constitute its other, if it has constituted itself according to this purposive entente with its outside, if it has always intended to hear itself speak, in the same language, of itself and of something else, can one, strictly speaking, determine a nonphilosophical place, a place of exteriority or alterity from which one might treat of philosophy?

Jacques Derrida, Margins of Philosophy

On the first day of spring 2015, shortly after completing the penultimate draft of this book, I flew to Kansas City and thence to St. Louis to give a keynote address at a theology conference on the theme of borders and boundaries.

Human beings do not simply think about themselves and others; they think through them. The same is true of events and objects or natural and supernatural phenomena; they are not only subject to thought but are the conditions of the very possibility of thought. This is why thought is always going on, even when we are not consciously thinking. By deconstructing the academic conception of philosophy as a uniquely European form of knowing, I hope to show that thinking is just one among many techniques humans have evolved for comprehending and negotiating the space between themselves and the world at large. Claude Lvi-Strauss asks why we readily accept the great antiquity of our species yet do not grant humanity a continuous thinking capacity during this enormous length of time. He sees no reason why thinkers of the caliber of Plato and Einstein did not exist two or three hundred thousand years ago, though they were, of course not applying their intelligence to the solution of the same problems as these more recent thinkers; instead, they were probably more interested in kinship!

As I was pondering these matters, I found myself distracted by the young woman in the window seat beside me. She had opened up a large drawing book on her tray table and was painstakingly copying an image of Lisa Simpson from the screen of her iPhone. Her concentration was remarkable, and though I had initially wondered why anyone would dedicate herself to such a banal project, I now become captivated by that dedicationas intense and compulsive as Casaubons academic labor on his Key to All Mythologies or Dorothea Brookes bedazzled attachment to her husbands delusional project.