Preface

F OR G IJA AND J ARU C HRISTIANS in Halls Creek, the story of Aboriginal people becoming Christian is not special. Everyone in the world today is becoming Christian (or is being given the opportunity to become Christian). All who have the ears to hear, and the sense to understand will accept the gospel message. When as many as possible are gathered unto him, Christ will come again. This is the message of evangelical missionaries in northern Australia.

For me, the story of the Gija and Jaru people is special. It shows Aboriginal peoples understandings of colonisation (and of black/white relationships) in northern Australia. It reveals the close connection between colonisation and Christianisation in Aboriginal Australia. Their story also shows the influence of indigenous religions on world religions. World religions, despite their love affair with the Beyond, deal in earthly life-forcesin potent energies which have travelled from indigenous religions through city-state religions to world-empire (and universal salvation) religions. These life-forces are today being returned to the depleted bodies of Gija and Jaru people in the form of Christs blood, bones and spirit.

I want to thank the Aboriginal adherents of the Assemblies of God and United Aborigines Mission churches for sharing their lives with me, for their love, humour and patience, and for frequently going far more than the extra Christian mile. Especially I want to thank Vera Cox, Wiby Essi, Jugarie, Doris Fletcher, Violet Rivers, Mona Green, Ruth Mills, and Bill and Bessie Matthews. Others who gave of their time and interest were Ethel Walalgie, Mavis Wallaby, Kathy Ryder, Marilyn Ryder, Stewart Morton, Musso Taylor, Muda, Barney Yule and Gladys Naparula.

I come from a long family line of Christian missionaries and evangelists. My great-great-grandmother, Susannah McDonald, left Glasgow in Scotland in the 1850s to become a missionary in Jamaica. She later settled in New Zealand. My father and three of his seven siblings became ministers in the same evangelical church. I spent my childhood following my parents ministry from one town to another in New Zealand. I also spent three years in a missionary Bible College. However, after working in community health with Warlpiri and other Aboriginal groups in Central Australia in the 1970s and 1980s, I became an anthropologist instead.

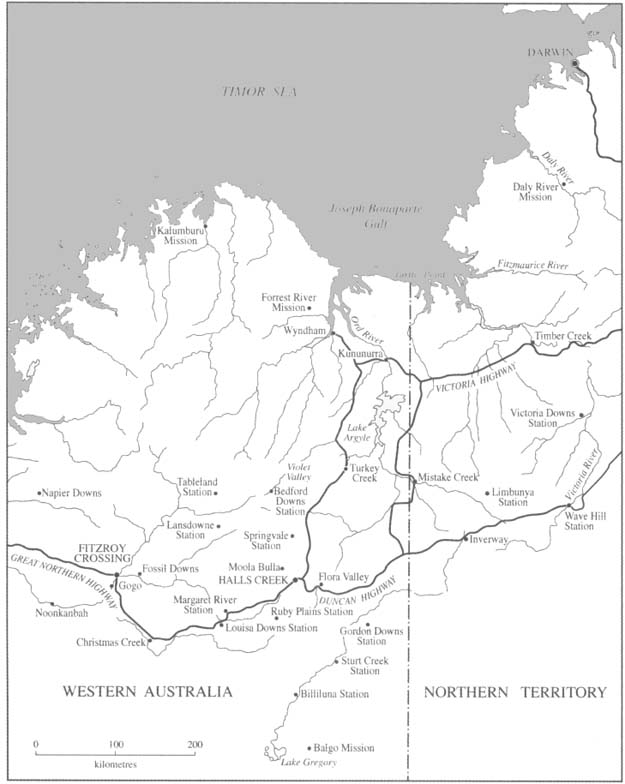

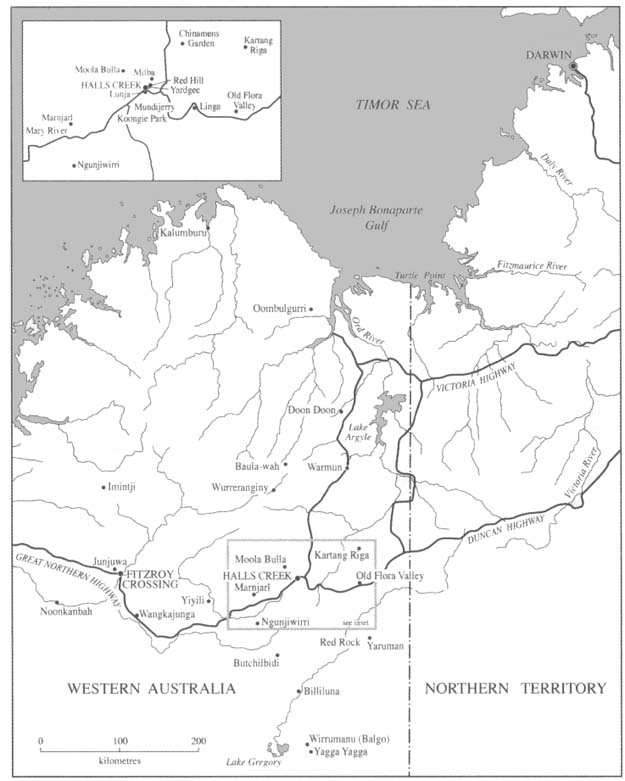

This book began life as a doctoral thesis in Archaeology and Anthropology at the Australian National University. My research was made possible by an ANU postgraduate scholarship and fieldwork research grant along with a research grant from the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. A vehicle was kindly provided by the North Australia Research Unit in Darwin. I thank Helen Ross for suggesting Halls Creek as a field location, for her affection and enthusiasm for the town and its people, and for her support and encouragement during my research. I am indebted to Ngoonjuwah Aboriginal Council in Halls Creek for giving me initial permission to study Christianity with Gija and Jaru people. I thank the Kimberley Language Resource Centre staff for making their facilities available to me, for their help with language learning and for their general support.

I am grateful to Ian Keen for supervising my doctoral thesis, for his patience and long-suffering support and for his critical comments on my thesis drafts. I thank Nicolas Peterson for his wise counsel and advice. I especially thank Francesca Merlan for having faith in me at a time when it seemed my work had come to a stop. I wish to thank my fellow ANU postgraduate students in Archaeology and Anthropology: Ingrid Slotte for conversations about Christianity and indigenous religions, and Aileen Toohey and Margaret Burns for helping me to clarify my ideas over numerous cups of coffee. Keiko Tamura and Christine Watson were ideal room mates during the writing-up period. Christine also introduced me to obscure untranslated texts by Father Peile of Balgo Mission. Jacqueline Ryle dispelled writing doldrums with breaths of fresh air from Denmark and Fiji. Elizabeth Barnes provided me with some welcome breaks from Canberra. I could not have finished this project without the friendship and support of these people. I am also indebted to the departmental secretaries, especially to Kathy Callen, for assistance and support.

Finally, I would like to thank the editors and support staff of Melbourne University Press: Teresa Pitt, the commissioning editor, for accepting my manuscript and for her interest and enthusiasm, Jean Dunn for her helpful comments and advice, and Craig Munro for his sharp editing.

Editorial Note

I N SPELLING A BORIGINAL WORDS, I have adopted the Jaru orthography developed by the Kimberley Language Resource Centre in consultation with Aboriginal speakers of this language. For the sake of consistency, I have also spelled Gija words according to the Jaru orthography. (See Glossary of Aboriginal Words.)

Although Gija and Jaru people live in the town of Halls Creek, they have not become city-state beings. They are most comfortable and relaxed when away from the constant and often contradictory demands of kin and bureaucratic institutions in East Kimberley towns. They consider themselves to be most at home in the countryside. I have therefore selected photographs which show Gija and Jaru peoples knowledge of country and its seasonal products, and their care for country.

In order to preserve the privacy of Aboriginal people and to protect their beliefs and values from unwanted scrutiny, I have elected to change all the names of Halls Creek people throughout this book.

Abbreviations

AIM | Aborigines Inland Mission |

AOG | Assemblies of God |

CMS | Church Missionary Society |

LMS | London Missionary Society |

UAM | United Aborigines Mission |

WMS | Wesleyan Missionary Society |

Introduction

W HEN I ARRIVED in Halls Creek to study religion and culture with Aboriginal people, Namaji, an old Gija woman, informed me that I could study language and bush tucker, but not Law.

However, as weeks and months passed, it became obvious that Halls Creek people follow their Law m all sorts of ways. They carry out obligations and responsibilities towards kin, their dead and the country. They believe strongly in balanced reciprocity and justice. Gija and Jam people participate in exchange systems that extend beyond their immediate kin groups into the Kimberley and Northern Territory. Aboriginal spirit worlds have not faded away with the onslaught of a colonial nation-state consciousness. Halls Creek people believe in the power of