ABOUT THE AUTHOR

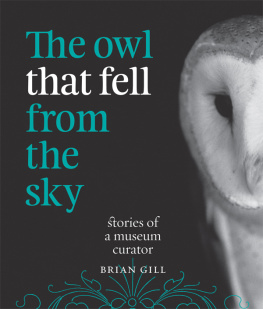

Brian Gill is the curator of land vertebratesbirds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals other than whalesat Auckland Museum in New Zealand. His research has included studies of New Zealand cuckoos, song birds and extinct birds, and field surveys of reptiles and birds on Pacific islands. In 2010 he received the Ornithological Society of New Zealands Robert Falla Memorial Award.

Also by Brian Gill

New Zealands Extinct Birds

with paintings by Paul Martinson

New Zealand Frogs and Reptiles

with Tony Whitaker

New Zealands Unique Birds

with photographs by Geoff Moon

The owl

that fell

from

the sky

Stories of

a museum

curator

brian gill

First ebook edition published in 2012 by

Awa Press, Level 1, 85 Victoria Street

Wellington, New Zealand

eISBN: 978-1-877551-49-9

Copyright Brian Gill 2012

The right of Brian Gill to be identified as the author of this work in terms of Section 96 of the Copyright Act 1994 is hereby asserted.

Copyright in this book is held by the author. You have been granted the right to read this ebook on screen but no part may be copied, transmitted, reproduced, downloaded or stored or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system in any form and by any means now known or subsequently invented without the written consent of Awa Press Limited, acting as the authors authorised agent.

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

Front cover photograph by Valerie Shaff, Getty Images

Book design by Pieta Brenton

www.awapress.com

Produced with the assistance of

Boy, that museum was full of glass

cases. There were even more upstairs,

with deer inside them drinking at water

holes, and birds flying south for the

winter.... The best thing, though, in that

museum was that everything always

stayed right where it was.

J. D. Salinger

The Catcher in the Rye

Acknowledgements

For companionship, inspiration and encouragement in the great task of developing natural history collections, I thank the technicians and volunteers who have worked with me on the Auckland Museum land vertebrates collection, my curatorial colleagues past and present at the museum, and curatorial friends and acquaintances at other museums, both in New Zealand and overseas. It has also been a privilege to work beside the other hands-on staff who make museums tick, including librarians, receptionists, display staff, conservators, educators, and maintenance and security staff.

I thank the many museum staff who have assisted my research on museum objects by providing information or giving access to objects in their care. The Bird Collectors by Barbara and Richard Mearns was a tremendously helpful source of biographical information on historical figures connected to natural history museums. I thank Liz Clark for sharing information on Rajahs life before he arrived at Auckland, and the Fanua family for hospitality in Tonga.

I wish to acknowledge a contribution to the cost of my side trip to Florencein search of the birds exchanged with Enrico Gigliolifrom the bequest of the late Dora Blackie. I am grateful to Nigel Prickett and Tony Whitaker for helpful discussions on various points. I appreciate Mary Varnhams expert attention in improving my prose and I thank Mary and the other staff at Awa PressSarah Bennett, Fiona Kirkcaldie, Kylie Sutcliffe and Ruth Beranfor the transformation of the book from concept to reality. Views expressed in this book are my own personal opinions.

Introduction

Rock pools at the end of St Clair Beach in the southern city of Dunedin are fixed in my childhood memories. During a weekend family stroll, I was fossicking among the pools when a small fish leapt out of the water and stranded on the rocks at my feet. It was shaped a bit like a tropical angelfish but with a long tubular mouth. I took it home and my father, with a vague idea of what to do with the now dead fish, put it into methylated spirits in a red Elastoplast tin.

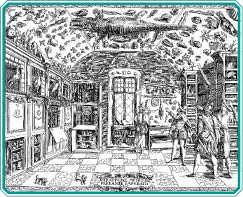

After school one day he took meand the fishto Otago Museum. I already knew the museum galleries from family visits but this occasion was different. We were shown through doors at the back into a large dim office lined with old books and dotted with specimen jars. I sat on the edge of a chair while a curator, who seemed very old but was probably not yet forty, closely examined the fish. Finally, he declared that it was a very interesting find, and I think he asked to have it for the collection.

Most natural history curators periodically meet children and their parents to examine an unidentified object and suggest what it might be. The curators office, workroom and kind words can make a big impression on young minds. I hope that, in my turn, I have repaid the experience I was graciously given by the curator at Otago Museum in the early 1960s. I have surely had a small impact on children visiting Auckland Museum, if only on the day I emerged from a back door into the Bird Hall wearing a white lab coat and pushing a trolleyload of stuffed birds. A small boy gasped and tugged at his mothers skirt. Look, Mum, he said, its a scientist!

You find a strangely shaped bone in your takeaway meal and have unsettling thoughts. What exactly have you been eating? You take the bone to your local health authorities and they refer it to the local natural history museum for a definitive answer. The expert staff who handle the museums reference collections of real bones quickly and accurately determine the nature of the bone.

This is a small example of why natural history museums are assets to the cities that have them. In such museums, collections of natural history specimens gradually build into a vast and immensely useful resource. Certain key specimens, perfectly preserved or beautifully set up, are exhibited in public galleries to educate and inspire visitors. Most, though, serve a more mundane role. Stored in backroom libraries, they are, by arrangement, accessible to people who are pursuing research projects, or seeking specialised identification of unknown material.

Next page