The Collected Writings of Modern Western Scholars on Japan, Vol. 5

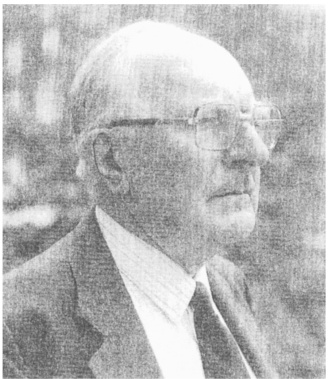

COLLECTED WRITINGS OF W.G. BEASLEY

This edition co-published by Japan Library and Edition Synapse, 2001

First published in 2001 by Japan Library

This edition published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

ISBN | (P.G. ONeill) | 1-873410-50-6 | (vol.4) |

(W.G. Beasley) | 1-873410-55-7 | (vol.5) |

(Ian Nish, Part 1) | 1-873410-60-3 | (vol.6) |

Vols. 4-6 ISBN 1-873410-98-0 (3-vols. Set)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the Publishers, except for the use of short extracts in criticism.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library

Edition Synapse

2-7-6 Uchikanda

Chiyoda-ku

Tokyo 101, Japan

ISBN | (P.G. ONeill) | 4-931444-37-7 | (vol.4) |

(W.G. Beasley) | 4-931444-38-5 | (vol.5) |

(Ian Nish, Part 1) | 4-931444-39-3 | (vol.6) |

Vols. 4-6 ISBN 4-931444-36-9 (3 vols. Set)

G.J. R ENIER , Professor of Dutch History in the University of London, was a man of wit and style, who taught me as an undergraduate and later supervised my doctoral research. He had an antipathy towards historians, whether young or old, who spoke of my subject or my period. The sin will be avoided in this introduction; but since the purpose is to offer an explanation of how the writings in this volume came about, the personal pronoun is all too likely to appear in other contexts. I apologize, both to readers and to Reniers ghost.

My first serious encounter with the subject of Japan arose from naval service during the Second World War. In the summer of 1943, having already spent some two-and-a-half years in the navy, I volunteered to learn Japanese. The reason was not an interest in Japan as such, but a desire to break new ground. The immediate result was fourteen months at the US Navy Language School in Boulder, Colorado. This was followed by shorter courses in Vancouver and New York, then transfer to the Pacific. After a brief excursion to the Philippine Islands, a hurried passage to Tokyo Bay for the Japanese surrender gave me my first experience of Japan. I landed in Yokohama in September 1945. The next six months were spent, first at Yokosuka at the US naval headquarters there, thereafter in Tokyo on the staff of the British mission. My duties were primarily concerned with preparing reports on the situation in Japan.

Nevertheless, on my return to England in the spring of 1946 there seemed no reason to suppose that Japan would play a part in my career. Like many others, my immediate aim was to resume prewar normality as soon as possible. Having completed a teacher training course and decided to go no farther along that path I set out to make a start on historical research, returning for that purpose to University College London, subsequently the Institute of Historical Research. I chose as a topic Anglo-Dutch rivalry in South East Asia in the seventeenth century, but soon encountered problems about access to the relevant materials. The Dutch archives in the Netherlands still suffered from the disruption caused by bombing and the German occupation. Those in Indonesia were inaccessible by reason of political turmoil in the region. It was in the light of these circumstances that Professor Renier suggested that I turn my attention to Japan.

An exploratory survey of Anglo-Dutch relations in Japan in the seventeenth century proved disappointing. Anglo-Dutch rivalry in Japan posed very similar problems of access to material as rivalry in South East Asia, though for slightly different reasons. This conclusion prompted me to begin a search through time to find a better thesis topic. It ended with the choice of Anglo-Japanese relations in the early and middle nineteenth century. Records concerning this could be found in some quantity in the admirable Foreign Office files, supplemented by those of other government departments and a few collections of private papers in Britain. Moreover, many of the Japanese records for the period had been published and the volumes I would need were to be found in the British Museum or the Bodleian Library. In other words, the topic was feasible.

The resulting dissertation was completed in 1950 and published in 1951, shorn of many superfluous notes and the detritus of earlier researches.1 A by-product was the article that forms the first item in this volume. In one respect this owed its separate existence to the fact that it needed to include some passages in Japanese (omitted in the present version), which would have caused typographical problems in printing the book. In another, it derived from the fortunate circumstance that both the British and the Japanese documents dealing with the negotiation of the first convention between the two countries in 1854 included diaries of the discussions between the British admiral and the Japanese governor of Nagasaki, who were the principal parties to them. These diaries were independently prepared and detailed enough to make comparison possible. Comparison revealed discrepancies. Examination of these led to the conclusion that the fault lay almost certainly with the interpreting, thereby opening up a line of enquiry into the background of the interpreters. Its results suggested that errors had from the start been probable, given that the participants in the talks belonged, not only to different countries, but also to different cultures, which had not been directly in contact with each other for over two hundred years. It would have taken an exceptional linguistic skill to have brought them to mutual understanding. This was not available.

Contents

Contents